When Rodrigo Duterte was inaugurated as Philippines president seven months ago, he came to office intent on starting one war – a deadly blitz on drugs with a body count now estimated at more than 7000 - and seeking to end another; the decades-old, low-intensity nationwide Communist insurgency estimated to have cost 30,000 lives since the 1960s.

In the last two weeks, the war on drugs has been placed on indefinite pause and the war against the Communist insurgents has restarted. Both are major setbacks for Duterte that put into stark relief the major policy planning and implementation problems besetting his administration.

Duterte put the 170,000-plus strong Philippine National Police (PNP) in charge of his signature war on drugs, not the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency that is part of the Office of the President and rated as one of the best performing government agencies in 2015. This, despite the PNP’s long-standing reputation for corruption, abuse of power and criminality. Now key members of the PNP group focused on illegal drugs are alleged to have lived up to and gone beyond this reputation for malfeasance. They have been implicated in the abduction, ransom and murder of a senior Korean businessperson on false pretences. An Amnesty International Report released on 31 January provides more evidence of the depth of these PNP problems.

The public airing of this case in January, aided by the persistence of the South Korean government and media, led to the announcement of the indefinite pause on the war of drugs for a period of PNP 'internal cleansing', the dismantling of the PNP illegal drug group, and the transfer of responsibility for the war on drugs to the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency. The fact that it took the death of a foreign businessperson, after months of media reports detailing Filipinos who were victims of PNP's abuses, for such a policy response adds to the political fallout.

This embarrassing setback poses two major problems for the President who put so much of his substantial political capital behind this war.

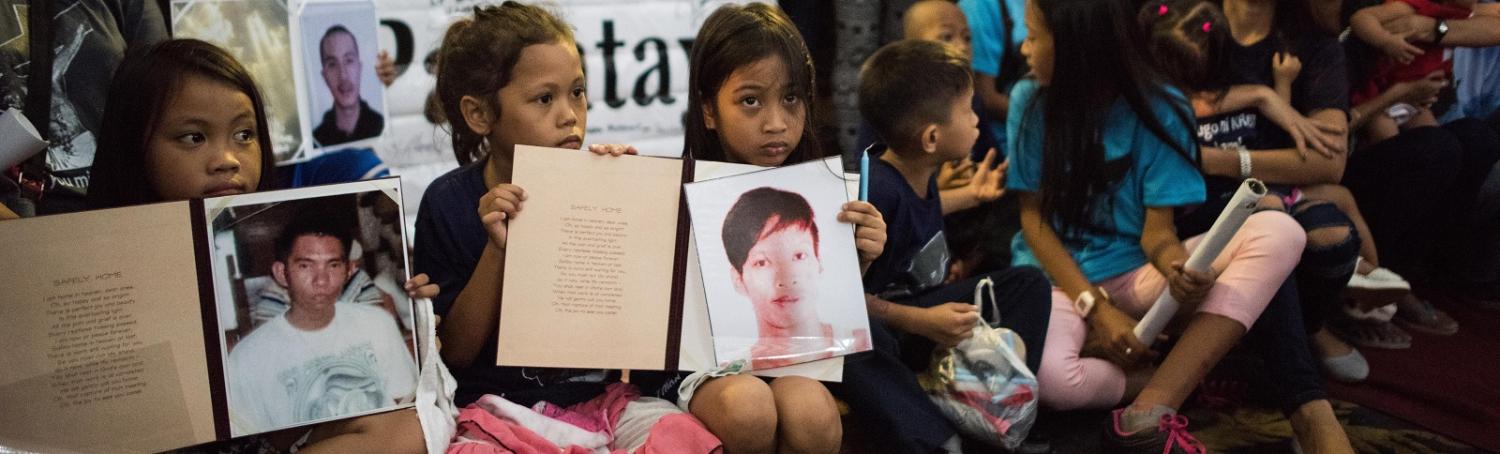

First, there are signs that the reversal and the media’s coverage of the tragic human costs of the war on drugs are leading to politically more meaningful opposition. On 5 February, a pastoral letter equating the war on drugs with a 'reign of terror' on the Filipino poor was read out in all Catholic churches. Philippines Vice President Robredo, who quit her Cabinet post in December in protest at some Duterte policies and whose office is providing free legal support for victims of the war on drugs, backed the letter and called it a potential tipping point. This is the strongest sign yet that Robredo may choose to accept the role that many of her supporters have asked her to take on and lead the opposition to the Duterte administration.

Second, the PNP is clearly not a suitable organisation to lead the war on drugs, even if so-called 'scalawag' police officers are banished to Mindanao, Duterte’s home island. However, the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency is much too small to take on the battle, at least as it has been conducted to date. At the end of 2015, this Agency had fewer than 1700 employees and 800 drug enforcement officers. President Duterte has called on the army to play a much larger role in his war on drugs and to arrest corrupt police officers as part of the PNP cleansing. Yet the army does not have the training (and likely not the desire) to take the lead in this war. Secretary of Defense Lorenzana has asked for a written order setting out the legal basis for this mooted crossover use of the army. No such order has been publicly released.

President Duterte has extended the deadline for the war on drugs from the end of December 2016 until the end of his presidential term in mid-2022 and continues to lambast anyone who criticises this, his signature policy. Yet with no clear suitable lead agency and rising opposition, it is far from clear when and how it can either start again or end successfully.

Part two in this series will examine the recommencement of 'all -out war' against the Communist insurgency in the Philippines.