On 8 May, the Democratic Republic of Congo notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of a confirmed outbreak of Ebola. Since early April, there have been 49 reported cases of the disease in Congo, including 26 deaths. While the majority of cases have occurred in the rural town of Bikoro, over the past week local authorities have confirmed four cases in Mbandaka, a city of 1.2 million people.

Soon after the outbreak began, the WHO, Congo, and international partners, including Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), launched a rapid and comprehensive response. The organisation and scale of this response contrasts sharply with events in 2013–16, after the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. That episode left more than 11,300 people dead, and resulted in strong criticism of delays in the WHO’s and international community’s handling of the crisis.

Now, the WHO has embraced its role as an operational organisation, activating its newly established Contingency Fund for Emergencies, deploying more than 100 experts to Congo, and, for the first time, using an Ebola vaccine to contain the outbreak.

Despite these advances, the response faces significant challenges, and the situation could deteriorate quickly. Countries must now match this rapid action by funding the WHO’s response and complying with its technical advice as well as international law governing the outbreak.

Urban danger

This is the ninth outbreak in Congo since Ebola was first identified in 1976 in the country’s north, then known as Zaire. Most outbreaks have occured in remote areas, contained by limited infrastructure and the natural barrier of forests.

Yet in the words of WHO Deputy Director-General Peter Salama, the cases in Mbandaka are “a game changer”. Not only do cases in an urban setting have a greater risk of spreading to more people, but Mbandaka also sits on the banks of the Congo River, which serves as a principal trade and travel route connecting major cities in the region, including Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Brazzaville, the capital of the neighbouring Republic of Congo.

These new cases prompted WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to convene an Emergency Committee of experts on 18 May. The aim was to determine whether the latest outbreak met the conditions for the declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) under the legally binding International Health Regulations (IHR).

A PHEIC is defined under the IHR as an extraordinary event that constitutes a public health risk to other countries through international spread, and which potentially requires an international response. The Emergency Committee noted that while there is a risk of international spread to neighbouring countries, and significant logistical issues reaching affected rural areas, the conditions for a PHEIC had not yet been met.

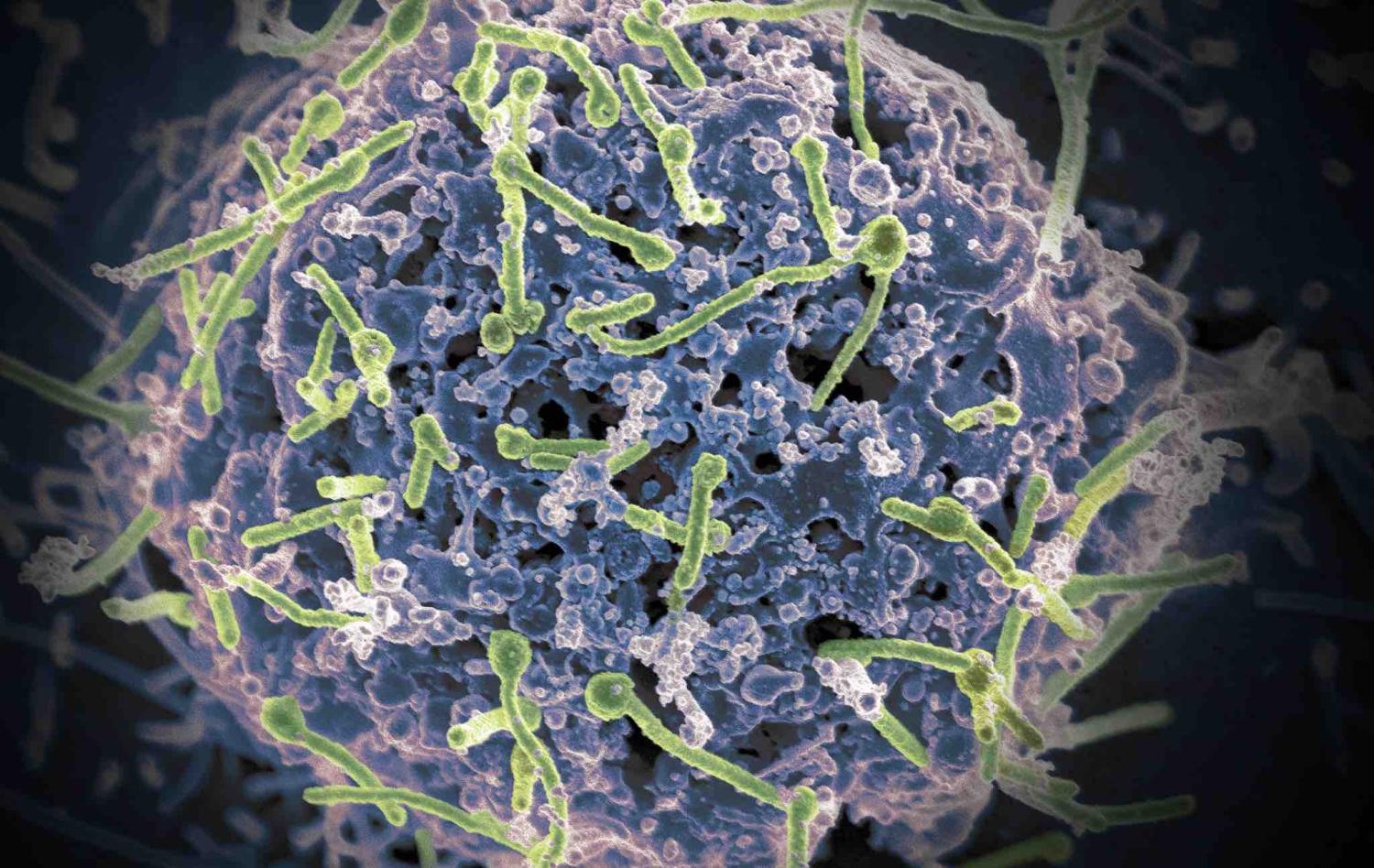

Critically, in addition to the rapid and comprehensive response to date, for the first time a new tool is available to control the outbreak: an Ebola vaccine.

Game changer: an Ebola vaccine

On Monday, the WHO, MSF, and other partners began distributing an experimental Ebola vaccine known as rVSV-ZEBOV. The vaccine will be provided to healthcare workers and administered using a “ring vaccination” strategy, whereby contacts of confirmed cases, and contacts of contacts, are offered vaccination to control the spread of the outbreak in a targeted manner.

More than 7500 doses of the Ebola vaccine have been donated by pharmaceutical company Merck, with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, contributing more than US$1 million to the operational costs.

International response required

While a PHEIC was not declared, the Emergency Committee advised that countries should not implement any international travel and trade restrictions. It also declared that entry screening “in distant airports” will not have any public health or cost-benefit value.

During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, some countries, including Australia, went against WHO recommendations and the IHR, implementing travel restrictions, such as visa bans. Such measures are not only ineffective, but also undermine public health efforts to control the spread of a disease.

The WHO estimates that controlling the outbreak will cost $26 million. In comparison, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa cost the international community $3–4 billion. At least $8.8 million has been raised in response to the latest outbreak, but additional financial support from the international community is crucial to containing the spread.

The WHO and international partners have responded with swift and comprehensive action. The onus is now on the international community, including Australia, to similarly respond decisively, providing the WHO with the funding it has requested, and refraining from implementing measures that are potentially detrimental to the response.

As Jeremy Farrar, Director of the Wellcome Trust, has said:

If this epidemic gets out of hand, which it could do, [the global community] will not be able to blame WHO this time.