Dismal science

Revision season is well underway at the top of the institutions that underpin the globalised economy, those same institutions now in the cross hairs of Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s audit of what Australia gets from globalism.

In the last week, the heads of the World Trade Organisation, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund have all downgraded their economic outlooks, setting the scene for a truly dismal annual gathering of the much maligned econocratic elite in Washington next week.

But, given the Prime Minister’s new preoccupation (revealed in his Lowy Institute speech), it may be more interesting to see what those leaders also offered up as successful outcomes from a difficult time for their institutions.

David Malpass, the still relatively new World Bank president, says the arrival of digital payments in less developed countries will transform development economics:

[They] would allow poor people to electronically receive remittances, foreign aid, and social safety-net payments as well as their earnings … That would be revolutionary because it allows people the freedom and opportunity they need to improve their living conditions.

The very new IMF managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, highlighted new agency research which finds that carbon taxes are one of the most powerful and efficient tools for dealing with climate change, making the point that:

Additional revenues could be used to cut taxes elsewhere and fund assistance to millions of affected households. These new resources could also support investments in the clean energy infrastructure that will help the planet heal.

Longstanding WTO director general Robert Azevedo notes that despite all the criticism of his institution, attendance at its annual public forum this week is up 30% on last year to 3200.

The enthusiasm has been reassuring. It means we're asking the right questions – and that we are working together to find answers.

It’s hardly stirring stuff, but count this as the first submission for the defence in Australia’s inquisition of “negative globalism”.

Off the graph

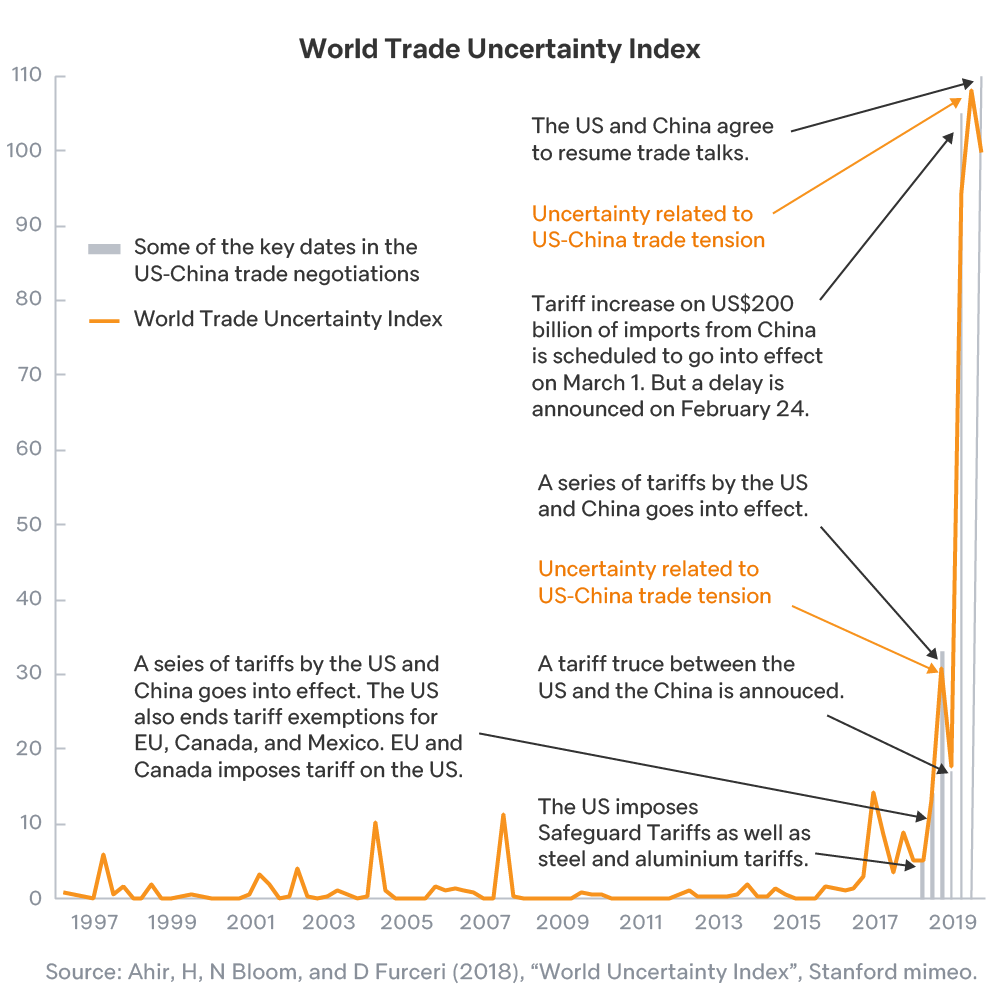

If the pointing scoring between China and the US and handwringing by economists about the future of globalism gets a bit repetitive, this chart puts the gloomy trade outlook in a new perspective.

It was published by some IMF economists last month in what they claim as the first attempt to chart global uncertainty about trade.

They make the striking point that uncertainty has risen about tenfold from previous crises in the past 25 years, including the Global Financial Crisis, the Asian Economic Crisis, and the serial failure of the Doha trade liberalisation negotiation.

And they say increases in uncertainty foreshadow significant economic output falls. So, the 2019 first quarter uncertainty spike could be enough to reduce global growth by up to 0.75 percentage point this year.

RCEP to the rescue

Amid the increasingly bearish tone from his global counterparts, Southeast Asia’s top regional official has doubled down on highly ambitious targets for greater regional integration.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) secretary general Lim Jock Hoi told a roundtable of regional editors in Bangkok this week that ASEAN was still targeting a doubling of intra-regional trade from the current 23% of total trade by 2025.* This would require trade between the ten member states to increase by around 9% a year, or more than double what it has been growing in recent years. That would certainly be far “beyond business-as-usual,” as Lim characterised the challenge to the roundtable hosted by ASEAN’s think tank the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA).

There is some nervousness that as the ASEAN chair country Vietnam may become preoccupied with curtailing China’s claims on its own South China Sea territory at the expense of pursuing the RCEP agenda.

However, ASEAN’s own integration measures such as the single customs window are still suffering teething issues despite being officially in place and non-tariff barriers are reportedly on the rise in the notionally near-zero tariff ASEAN Economic Community.

So, getting anywhere near achieving this target may increasingly depend on the successful completion of the 16-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), with ASEAN notionally at its centre.

Trade ministers are back in Bangkok later this week trying to deliver a deal for the Thai-hosted East Asia Summit in early November, with Lim still only prepared to say cautiously that a “conclusion is in sight”. But it seems more likely that while Thailand might get close enough to claim an in-principle deal, the details will still be left for ASEAN’s next chair country, Vietnam, to see through to a signing ceremony next year. Vietnam has been the region’s standout freer trade flagbearer in recent years with a series of bilateral deals and its participation in the revamped Trans-Pacific Partnership.

But, interestingly, there is some nervousness that as the ASEAN chair country Vietnam may become preoccupied with curtailing China’s claims on its own South China Sea territory at the expense of pursuing the RCEP agenda.

Regions rule

Increased regionalisation is the one positive in the latest gloomy assessment of the state of globalisation to come from the financial market economists, who have long thrived on the process.

Capital Economics says globalisation has peaked in this series of assessments, which observes that new technologies have reduced the need for businesses to maintain large and complex supply chains, typically underpinned by liberalised trade regimes.

The Capital economists warn that the risk of “a period of de-globalisation is underappreciated”, but it is not clear how it will unfold.

At one end of the spectrum, we could see a mild form of regionalisation, in which production is clustered in neighbouring countries rather than globalised. At the other end of the spectrum, the world could split into competing blocs.

But they say regionalisation would not be a big problem, given that a lot of trade already takes place between neighbouring countries and regions would probably be big enough to sustain global companies.

* Greg Earl was a participant in the ERIA Editors Roundtable.