New chapter

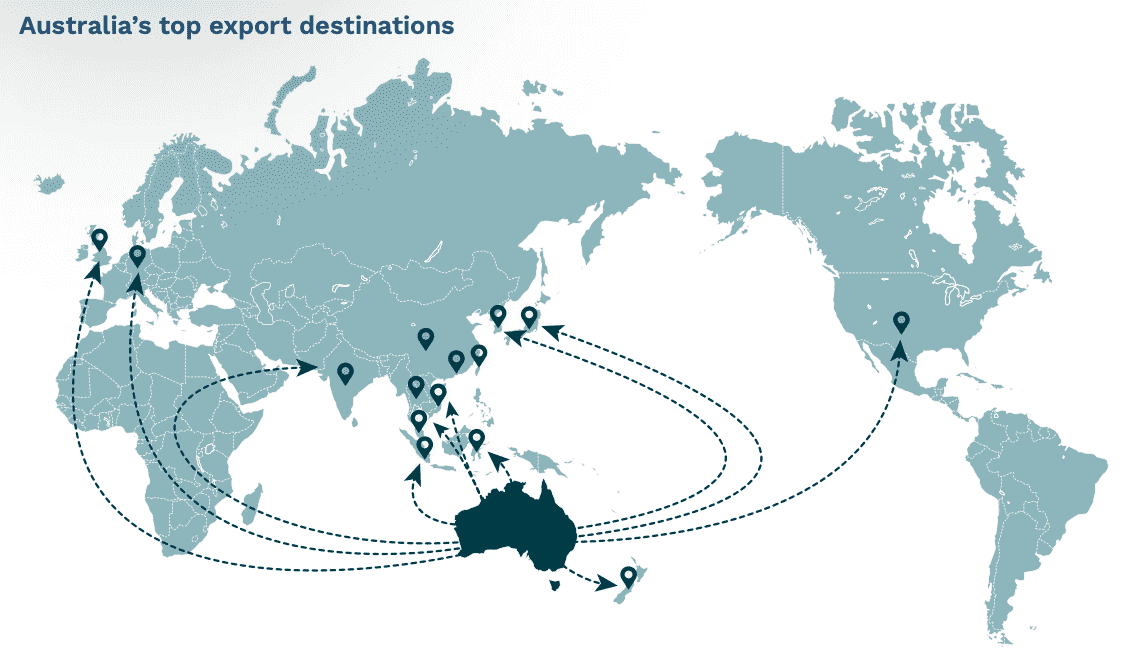

It may not have been intended, but a map deep inside last week’s federal budget papers seems to sum up the Australian government’s economic diplomacy strategy: preparing for life after China.

While it is titled “top export destinations”, arrows zoom to all major trading partners, apart from the largest one which accounts for more than a quarter of two-way trade and almost a third of exports.

Indeed, China is referred to only seven times in the more than 300 pages of the core Budget Strategy and Outlook paper. That compares with 30 times back in 2015–16, when the bilateral trade deal and the now suspended Strategic Economic Dialogue were getting under way. That budget paper even featured special (and optimistic) analysis of Chinese economic growth and tourist arrivals to Australia, compared with the one handed down last week, when the government was more preoccupied with comparing Australia’s post-Covid outlook favourably with the old Group of Seven economies.

While China made it to the second page of the budget strategy text in 2015 with its “strong contribution to global growth”, this year it takes 38 pages to learn that Australia’s largest trading partner has “already returned to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity”.

And the old reality of what that means for Australia is finally almost grudgingly acknowledged a couple of pages further on, when the budget notes that Australia’s major trading partners (MTPs) are growing faster than the global economy, “partly reflecting China’s larger weighting within Australia’s MTP basket”.

Changing the oil

While longer border closures and funding for bringing more Australians home dominated the headlines, the crucial international relations theme in the budget is about trade diversification (away from China) making the economy more resilient.

After years of spending cuts for diplomacy amid increased spending on defence and intelligence, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade seems to have finally hit on a successful budget strategy. Last year, it scored an extra $25 million a year to wade through the 1000 state, local and university agreements that fall under the new Foreign Relations Act. This year, it has won most of $198.2 million over four years (and $33 million a year after that) to be spent on “Enhanced Trade and Strategic Capability”. This funds export diversification, World Trade Organisation reform, the free and open Indo-Pacific policy and an expanded diplomatic network.

The big-spending budget suggests the ground is shifting ahead of an election.

This is the core of new spending on trade diversification. But depending on how these things are defined, there is at least $500 million of obvious new money over four years on trade diversification initiatives covering supply-chain resilience, simplified trade, anti-dumping and farm exports.

Despite talking a lot about national resilience amid the toilet-paper crisis last year, the Morrison government has been relatively restrained about embracing the global reshoring mantra. It has flagged purchase guarantees and other support for new vaccine plants and announced a ten-year manufacturing strategy partly focused on export diversification.

But the big-spending budget suggests the ground is shifting ahead of an election. These decisions have been announced before the government gets the supply-chain resilience study it has commissioned from the Productivity Commission, which has already warned about throwing money at trade risks which do not really exist. The ground shift was quickly confirmed this week when the suggestion of an oil security initiative in the budget morphed into the most expensive Australian reshoring move yet: the $2.4 billion plan to keep two oil refineries in business for the next decade.

While Prime Minister Scott Morrison dressed this up as support for refinery workers and cleaner cars for everyone else, it shows how fear of a shipping crisis and a war with China is now driving an expensive new industrial policy.

Aid vs trade

One way to look at the cash splash on trade diversification is to compare it with the curious pea and thimble game which has been going on with development aid spending in the past year. As Lowy’s Jonathan Pryke has already detailed, long-term official development assistance (ODA) is stuck at about $4 billion a year, and thus potentially trending down in real terms.

But the government still has a couple of years of regional diplomacy talking points from the $1.3 billion in “temporary, targeted and supplementary measures” on vaccine, economic support and other new aid for the Pacific and Southeast Asia which it announced mostly outside last year’s budget. Some measures last until 2024.

While aid advocates are concerned about the apparent $4 billion ceiling on long-term standard aid, the government seems focused on special announcements at diplomatic gatherings which don’t spoil annual budgets targeted at possibly aid-sceptical voters.

So, it should not be a surprise to see more “temporary, targeted and supplementary measures” on climate change ahead of the Glasgow Conference of the Parties (COP) meeting (this week’s low-sulphur fuel initiative could meet that standard) or on Myanmar ahead of the next summit for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. This doesn’t make for the carefully planned multi-year normal aid projects sought by the aid sector. But it seems to be the new reality of battling for hearts and minds amid superpower rivalry and uncertainty about the reliability of regional groups such as ASEAN and the Pacific Islands Forum.

The fact that the government is being attacked for not budging on the $4 billion ODA amount when it is still sitting on at least two years of unexpected supplementary spending from last year only seems to explain its opaqueness about adding the new pandemic spending to the official aid figure.

Now, this is a case of counting apples and oranges with arbitrary definitions. But some rough calculations suggest the government is locking in at least $400 million a year (for many years) on post-China trade diversification policy with measures such as the manufacturing strategy, the fuel subsidy scheme and the latest budget trade spending.

That is ironically roughly the same as last year’s $400 million a year (for only three years) in special aid funding, which is also partly driven by regional aid rivalry with China.

The price of power

One of the most interesting changes in federal government budgets is the way the cost of iron ore has arguably supplanted the Aussie dollar as the price to watch in international relations. This was underlined in the days leading up to the budget’s release with little debate about how the currency traders would view yet another big-spending Australian government.

Instead, all the attention was on how Treasurer Josh Frydenberg would deal with the irony that one of his biggest revenue variables is determined by Chinese demand for iron ore.

In the end, Frydenberg took the prudent course of sticking with a budget that features an iron ore price of $55 a tonne, which is well below the recent record price of more than $200. The difference is worth about $12 billion a year in tax receipts.

And the price of the commodity has now taken on some of the role the dollar used to play in political debate.

Defence hawks tend to see the current high price as evidence that China’s economic coercion has failed and that Australia has a stranglehold on the supply of raw material crucial to Chinese growth. On the other hand, the China lobby fears the price will tumble when Beijing planners secure new supplies in Africa, finally demonstrating that Australia is really just a price taker in a China-led regional economy.

Former treasurer Joe Hockey, who oversaw that Sinophile budget all the way back in 2015, has provided an insight into how this debate has actually been running for a long time. The Australian Financial Review revealed last weekend that in 2014, Hockey was desperately trying to cut budget spending with iron ore tumbling from a then $190 a tonne record to below $80. So he decided to find out who really pulled the levers during a private meeting with his Chinese counterpart Lou Jiwei.

In short, Hockey says he told Lou that if China let the price go below $38 and wrecked his budget credibility, he would let BHP and Rio Tinto merge so they could muscle up to their biggest customer. Lou apparently got the message and the price only dropped to just below $50 – but Hockey still lost his job.

Frydenberg should be glad he is not trying to plot a Covid economic recovery with iron ore actually at $55 and all the phone lines to Beijing unanswered these days.