Elbows out

Is there a better case study in the curious politics of geo-economic fragmentation than Australia’s latest effort to revive manufacturing? Prime Minister Anthony Albanese last week set out an ambition for a “future made in Australia”, and in doing so has blamed five of the country’s closest economic and security partners for his flagship return to big government, when it is ultimately driven by concern about excess capacity in its unnamed biggest trading partner (i.e.: China).

Albanese’s pledge follows the global industrial policy renaissance sweeping the world – from the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to Narendra Modi’s “Make in India”. Yet Australia’s version last week arrived with presumably unintended exquisite timing.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was just releasing its stepped-up monitoring of what its staff warn “is costly, and can lead to various forms of government failures ranging from corruption to misallocation of resources.” And US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was doing another good cop routine in Beijing on energy transition technology by declaring: “Our concern about overcapacity is not animated by anti-China sentiment or a desire to decouple.”

Nevertheless, in Albanese’s effort to blend a job creating domestic manufacturing policy with sounding tough on national sovereignty, the PM says his proposed (and noticeably Modiesque) Future Made in Australia Act will give Australia “sharp elbows” in a changed world. As he put it: “Nations are drawing an explicit link between economic security and national security … This is not old-fashioned protectionism or isolationism – it is the new competition.”

New competition or not, the IRA-style plan to unify a mixed bag of green energy, sunrise industry and R&D tax incentives under a populist sounding program is provoking widespread debate about how the country should best position itself in the new era of revived industry policy. Australia has done as well as any country from the fading globalisation era as a competitive resources exporter and emerging services supplier at the cost of a less protected manufacturing sector.

New for old

Labor only came to office two years ago with an ambitious rebuild manufacturing policy, picking up from its short-lived predecessor in the 2000s. This stands in contrast to the long-serving Labor government of the 1980s, which backed far-reaching economic reforms and especially trade liberalisation at some cost to its union base, setting the country up for a long period of productivity growth.

The current government has introduced a range of new funds and programs in green energy, critical minerals development, and national reconstruction (i.e.: manufacturing) – but it also faces some criticism they are confusing and uncoordinated.

So Albanese may be in effect addressing this with his new coordinating mechanism ahead of splashing out even more money.

Or this may be more about refurbishing old policies for a tight election battle by early next year with the added packaging of national security.

Nevertheless, the new spending has already begun this week with a $400 million government loan to a green alumina project with the money coming from three separate funds. That could be viewed as a sort of innovative industry policy network effect or alternatively as just an opaque way of providing government assistance.

And it is notable that as Treasurer Jim Chalmers headed to the IMF meetings on Wednesday, for the second time this week he played down the prospect of massive new spending, declaring the government would only provide a “tiny sliver” of the $225 billion needed for the energy transition to 2050.

Frenemies vs friendshoring

The Albanese government has spent much of the past year calming concerns in Japan, South Korea and Singapore that its fossil fuel replacement green energy policy and pro-manufacturing domestic gas reservation policy might hurt those countries’ energy (and thus national) security. Indeed, Japan’s former ambassador left early partly because of his public criticism.

So, it was interesting to see Albanese accuse Japan and South Korea, along with the United States, the European Union and Canada, for sucking investment capital away from Australia by “investing in their industrial base, their manufacturing capability and their economic sovereignty.”

From the Five Eyes intelligence group to the mooted Democracy 10, these are the countries that Australia is increasingly aligning with to cope with the geo-economic fracturing caused by the rise of the Global South, especially China. But in this new era, it seems South Korea might be a friend-shorer when it comes to obtaining batteries from somewhere other than China but more of a frenemy when it comes to attracting capital.

Albanese’s targeting of these allies for capital competition was a different tone to that struck earlier this month by a key figure in the new Labor power structure – former union leader and minister turned fund manager and renewable energy advocate Greg Combet. He was warning against competing with the deep-pocketed manufacturing powers on industry policy and instead reassuring them about energy security by offering them key roles in Australia’s development of new resources such as hydrogen.

Too much is not enough

China’s complete omission from Albanese’s manufacturing announcement says a lot about how much the government is tip-toeing around China’s state-led economy – with a much older Made in China policy – and the fundamental role that is playing in the renaissance of industry policy elsewhere. China’s industrial output has risen about 25 per cent since 2019 raising fears it could flood the world with cheap, but this time quality, products.

Indeed, while the United States and the European Union are pondering new restrictions on Chinese renewable energy from solar panels to electric vehicles, the Albanese government has highlighted its closure of the same dumping inquiry into Chinese-made wind turbines twice in the past year. Each conveniently coincided with bilateral visits by Albanese and then Foreign Minister Wang Yi as part of the stabilisation of relations process.

Chinese investment in Australia has been declining since 2016 and public opinion seems to have turned more positive towards the country, but the government can still be reasonably confident that just talking about national security evokes worries about Beijing’s assertiveness in the minds of most voters. However, they apparently need reminding about the other countries in Albanese’ speech.

Australia’s experience of Chinese economic coercion means it is only prudent to be at least rethinking its dependence and the need for at least some more self-sufficiency. But its acceptance of imported Chinese wind turbines to help achieve its energy transition needs also marks it out as more pragmatic than some other countries.

With many countries, including Australia, struggling to meet emissions reduction and energy transition targets, the world may well face an invidious choice between taking advantage of China’s excess capacity in new energy technology or failing to stop global warming. Hopefully the choice is not so binary with the rise of competing industrial policies, but it is hard to ignore the vital role Chinese equipment can play despite the national security fears.

A greener shade of pain

The release of research for this week’s annual gathering of multilateral financial agencies in Washington was quickly used by critics of Albanese’ Made in Australia policy to argue he is on the wrong track.

But a closer reading of the IMF Fiscal Monitor chapter on innovation and technology diffusion says as much about the institution coming to grips with the new geopolitical reality of industrial policy and climate change as it does about the Australian government’s search for a rebadged pro-manufacturing election campaign.

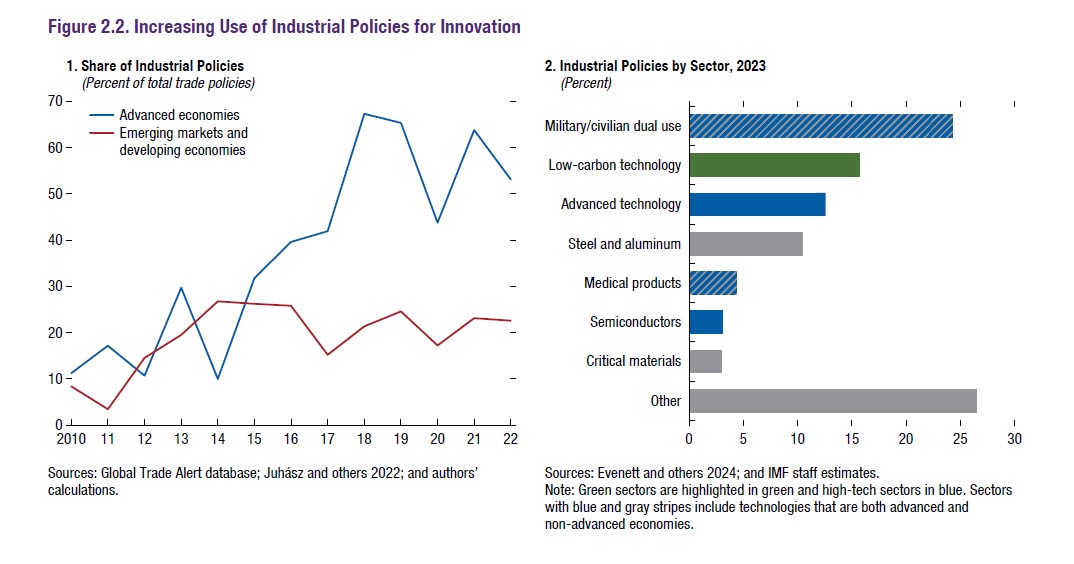

The key finding from the IMF’s new partnership with Global Trade Alert to monitor industrial policy is that advanced economies are overtaking emerging economies in their use of these measures (see the graph above). This is a turnaround from when developing countries used these polices to try to catch up with the rich world and were often criticised by the IMF.

The shift is driven by the competition between the United States and China but is now clearly filtering down the pecking order to the likes of Australia. At the global level about 25 per cent of new industrial policies last year were for military/civilian dual use rather than fields such as critical minerals or medical products, underlining the tilt towards hard national security compared with softer national security.

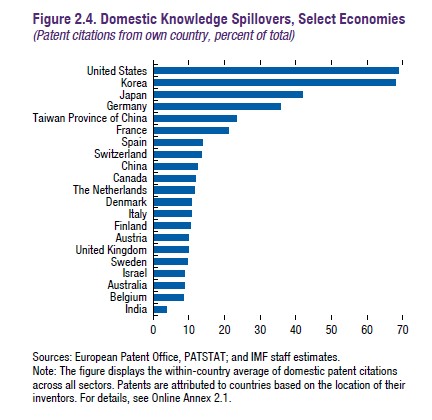

The IMF repeats its fairly routine thinking that these measures might be useful if they are carefully applied at the upstream level in the form of targeted education and research spending to possibly stimulate and support new industries, rather than in the form of picking individual producers at the domestic level and even worse disadvantaging foreign players. Indeed, there is a telling chart in the Fiscal Monitor (reproduced here) which suggests that Australia, as a small open economy which draws heavily on knowledge spillovers from abroad rather than from home, benefits much less from industrial policy style measures.

However, the second biggest sector for the application of industrial policies last year was low-carbon technology (at a bit more than 15 per cent) and the IMF research takes a distinctly more positive view of this because it now firmly accepts that the energy transition has positive externalities. It argues: “Higher subsidies for green innovation may be warranted given the imperative to decarbonise economies, but these should be transparent, focused on environmental objectives, and complemented with robust carbon pricing.”

This is a very useful measuring stick for judging Labor’s new embrace of industrial policy. But unfortunately, Albanese’ memories of the last Labor government implementing a carbon price in 2010 would be more painful than memories of its parallel only modest success reviving manufacturing.