Prosecutorial democracy

South Korea has a curious habit of investigating, often jailing, and then pardoning former presidents since it embraced two-party democracy with particular enthusiasm four decades ago.

Now Australians may be about to get a ringside seat on this distinctively hardball approach to politics in their fourth-largest trading partner. Demands are growing to recall the newly arrived Korean ambassador Lee Jong-sup.

While former prime minister Kevin Rudd’s future as Australian ambassador to Washington might depend on whether Donald Trump returns to the White House in November, Lee’s future seems to hang on how his patron and President Yoon Suk-yeol views his prospects in the Korean National Assembly election in just three weeks.

On Wednesday, Yoon caved into growing criticism of Lee’s appointment to Canberra less than three weeks ago and a subsequent damaging split in his party over the issue, by calling Lee back to Seoul for a hastily rescheduled ambassadors' meeting on Monday.

Whatever happens next, the Albanese government’s efforts to build a new middle power equilibrium in the region to manage the rise of China with emerging partners such as Korea seem set to be partly hostage to uncertainty about Lee’s stature as corruption investigations continue into his actions as a minister.

And coming after Japan recalled its Australian ambassador Shingo Yamagami early last year after his unusual jarring public comments on the Albanese government’s approach to China and renewable energy, the Korean case only underlines an old reality – even before a potential Trump renaissance. Despite the best intentions of diplomatic and security planners, domestic politics almost always comes first.

Playing defence

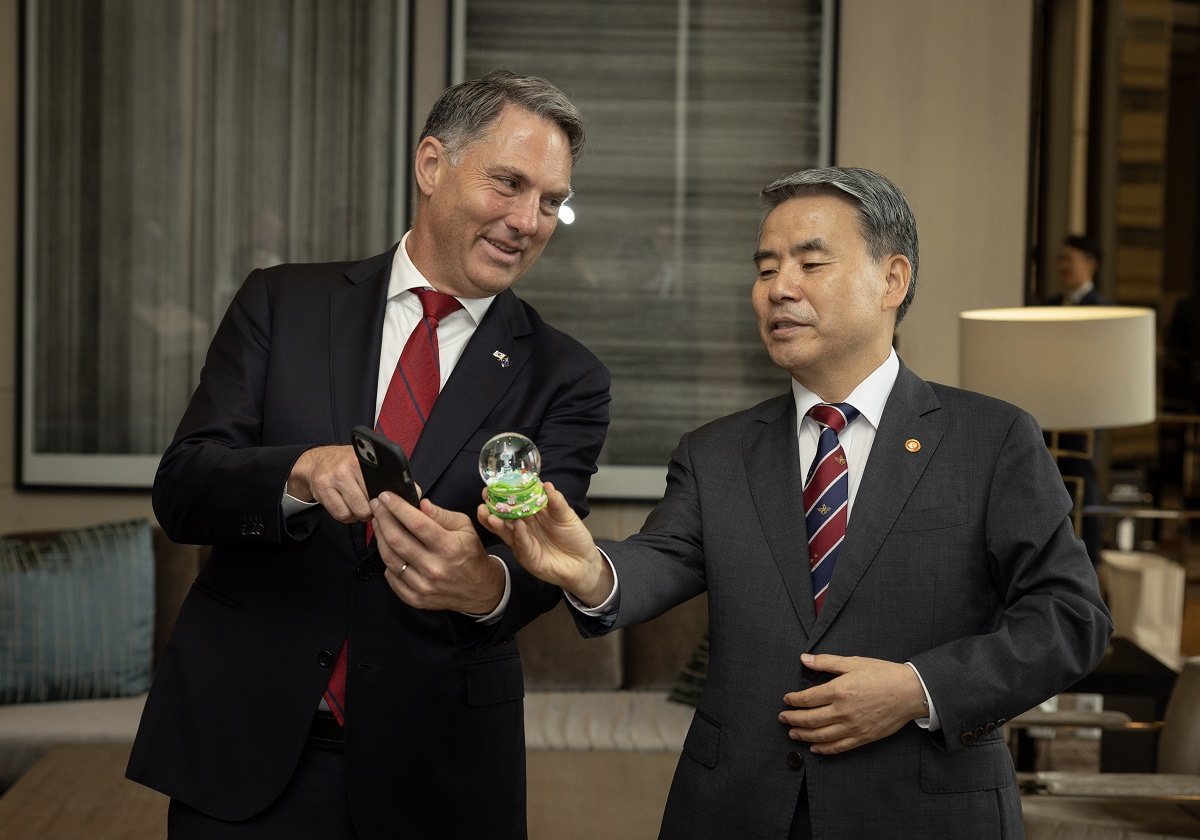

Less than a year ago, Lee, a former general turned Minister of National Defence in the conservative Yoon administration, was signing onto a new cooperation framework with Australia’s Defence Minister Richard Marles in Seoul, which included joining Australian naval drills and cooperation in the Pacific.

So, at face value, Lee looks like a good ambassador to help smooth over the underlying tensions from Australia’s decision following the Defence Strategic Review to cut back earlier planned defence purchases from Korea and instead focus on the mutual interests in broader security cooperation. As Marles put it last May: “Defence Minister Lee and I have met on a number of occasions now over the course of the last 12 months … there is just a really big opportunity to take this relationship to a different level.”

But that was before Lee became involved in a typically convoluted Korean political scandal, where a fiercely independent and adversarial judicial system modelled on the United States collides with a hyper-competitive two-party political system grafted on to an economy with powerful vested interests.

Lee resigned as defence minister last September along with five other defence and presidential officials. This followed allegations they curtailed an investigation into the death of a soldier who drowned during floods last July, possibly due to inadequate search and rescue equipment. Media reports suggest this was done at the behest of Yoon. The Corruption Investigation Office for High-ranking Officials (CIO) has been pursuing the case.

Hankyoreh newspaper suggested this week that the only justifiable reason for so many senior security officials to resign at once would be a serious national emergency, indicating there was some more political reason. “With so many defence officials exiting all at once, it became impossible to summon them to a parliamentary audit so that the National Assembly could properly question them on the details of the investigation,” it said.

Then early this month, Lee was suddenly appointed ambassador to Australia, ending the term of the 14-month incumbent career diplomat Kim Wan-joong. Lee then arrived in Canberra on 10 March, far from the domestic corruption crisis, after an investigation-related travel ban was curiously lifted two days earlier. Apart from the suddenness of the change, it also reportedly represents an unexplained upgrade in the stature of the Canberra post to the ex-minister level previously only applied to the United States, China, Japan and Russia posts.

That would suggest a welcome upgrade in the bilateral relationship under normal circumstances, but only time will tell whether that is actually the case.

Hey, big spender

For all the recent talk about building a middle power security partnership of equals with Korea, the country’s long-standing importance as a trading partner and emerging investment source for Australia tends to get ignored – possibly because there are no diplomatic spats.

Indeed, Korea hasn’t had a cut-through champion at the top-level ranks of Australian government since former prime minister John Howard took to hailing the top executives of the Posco steel company as his best customers due to their huge iron ore and coal purchases.

Indeed, the five-year trend growth for Korea as an export market of 13.2% now exceeds China, Japan, India and the United States. But Korean investment in Australia lags the trade relationship at only the nineteenth-largest inbound investor. That means a decision to award Korean company Hanwha the contract to build Australian infantry fighting vehicles at a factory near Geelong has significance beyond security by potentially encouraging more diversified Korean investment here outside the resources sector.

Lonely at the top

Yoon only narrowly won the 2022 presidential election for the conservative People Power Party (PPP) against the incumbent left-wing Democratic Party as a security and social conservative but economic liberal. More importantly, given the current imbroglio, he presented as a swashbuckling and independent-minded national prosecutor general who had pursued former conservative presidents for malpractices while in office.

But with the Democratic Party still controlling the National Assembly and erratic but declining personal opinion poll figures, Yoon has turned more to the international arena to make a mark as president, including being one of the few state visit invitees to the Biden White House.

The 10 April National Assembly election will determine whether he serves out the remaining presidential term with any legislative clout or as more of a lame duck president. And the electoral outlook is quite volatile with new breakaway left-wing and right-wing parties challenging the two major parties.

But this week, the Lee saga morphed into a key election issue with even PPP chief Han Dong-hoon, also a former prosecutor, breaking with his president to say Lee should be recalled from Canberra. Han, who is touted as the likely PPP replacement for Yoon at the 2027 presidential election, seems to have already scored another victory over Yoon by calling for, and winning, the resignation this week of another presidential adviser over a separate dispute with the media.

This week, Korea hosted its third Summit of Democracy underlining its world-beating economic and political transformation since the 1950s war. But its feisty style of adversarial politics has been coming under some scrutiny amid the global debate about the future of democracy, with some measures showing a decline in the quality of the country’s system. Some Korean commentators have called it a form of prosecutorial democracy where the combative tactics of a politicised, top-down prosecution service influence the way national policy is made.

Yoon and his mercurial party chief each built their careers by prosecuting former conservative presidents – Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye. They must be only too aware of the potential long-term implications of the CIO now launching investigations into the handling of the Lee affair by Yoon, his justice minister, and his foreign minister in addition to the original military death inquiry.