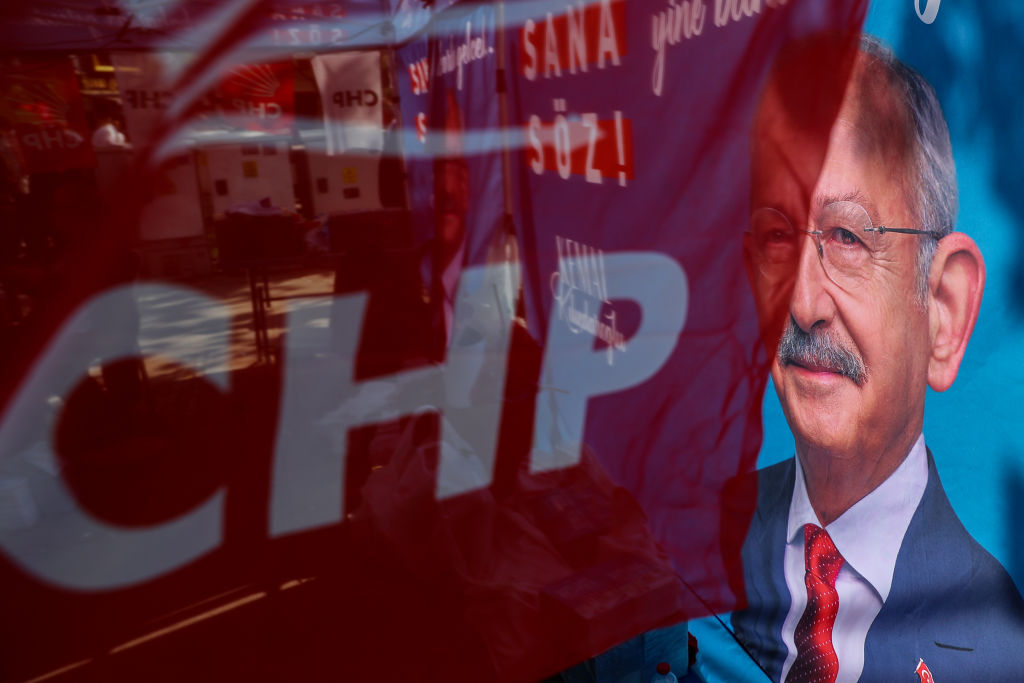

Turks go to the polls for presidential and parliamentary elections on 14 May. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been at the centre of Turkish politics since 2002, but change may be in the offing. Erdoğan is bracing for the fight of his political life. He faces a collapsing economy, fallout from the February earthquake, a cohort of first-time voters who are not well disposed to him, and a re-invigorated opposition that has rallied around a single candidate, the mild-mannered Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu.

A change in government would be momentous for Turkish citizens, a generation of which has known only Erdoğan’s rule. It is also likely to shift Ankara’s international posture. Since the participation of Turkish troops under UN command in the Korean war, Türkiye has been considered an ally of the West, yet it has never been fully embraced. US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken recently remarked that Türkiye was a “challenging ally”, and, tellingly, Türkiye was not invited to attend US President Joe Biden’s recently convened Summit for Democracy.

Such ambivalence arises from the undermining of democratic norms as Erdoğan has tightened his political grip and from a recent spate of assertive Turkish foreign policy initiatives. Of concern have been Türkiye’s repeated interventions in Syria, striking Kurdish forces that have been key US allies in the fight against ISIS but that Ankara deems terrorists. In Europe, Türkiye has ruffled feathers in claiming an economic exclusion zone in the eastern Mediterranean, Erdoğan further raising tensions by threatening Greece, and it has refused to approve Sweden’s entry into NATO after claiming Stockholm harbours purported terrorists.

Further afield, Ankara has forcefully imposed itself into regional conflict zones, having previously demurred. In 2020, Türkiye despatched Syrian militia to bolster its regional ally Azerbaijan in its campaign in Nagorno-Karabagh, while sponsoring other Syrian forces to intervene in Libya in support of the Government of National Accord.

For decades, Ankara aimed to foster ties with Europe and the West and paid little heed to its immediate neighbourhood, but in the last 15 years Türkiye has engaged more actively in the Middle East. This was not necessarily solely Erdogan’s doing. Foreign Minister from 2009 Ahmet Davutoğlu devised a “zero-problems-with-neighbours” policy that saw Turkish outreach in Arab states and closer relations with Iran. This initiative had varied impacts. Erdoğan won approval on the Arab street. He was the most widely admired international leader in a poll during the 2011 Arab Spring. Yet some interpreted Türkiye’s warming relations with its Middle Eastern neighbours, coupled with Erdoğan’s fractious interactions with Europe and his cosy relationship with Vladimir Putin, as a repudiation of the West. Some observers were moved to ask “who lost Turkey?” Such a perspective is reductive at best especially considering that Erdoğan’s abrasive style on the international stage has also raised hackles with regional players such as Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

Another viewpoint has been that under Erdoğan Türkiye’s politics and foreign outlook is increasingly shaped by Islamist sensibilities. Episodes such as Erdoğan’s invitation of Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal to Istanbul and his affinity for the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt heightened such concerns. This idea, too, is overly simplistic. After 20 years in power, Erdoğan is a supreme pragmatist, making alliances where they are to his advantage and periodically speaking out against the West to rally domestic political support.

Early in Erdogan’s tenure he was admired as a reformer and Türkiye was viewed as providing a model that married Islam and democracy and could be replicated elsewhere. But as one analyst argues, Türkiye under Erdoğan now has fewer friends, less diplomatic heft and is increasingly isolated.

Should the opposition win on 14 May, it will aim to address this situation, revising Türkiye’s current domestic and international trajectories. The end of Erdogan’s one-man rule would lead to institutional recalibration, allowing the Foreign Ministry, which has been subdued, greater policy-making authority.

A new administration would also move to buttress Türkiye’s democratic credentials. Ünal Çeviköz, an adviser to presidential candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, states that an initial step will be to reassure allies that the country “is back on track to democracy.” This will include complying with European Court of Human Right’s rulings requesting the release of imprisoned human rights defenders and politicians.

Rebuilding relations with Europe would be a priority. Kılıçdaroğlu has stated that if he wins office, he will move to meet requirements for Schengen visas for Turkish citizens. He is also likely to resuscitate Türkiye’s EU accession bid, begun to great fanfare under Erdoğan in 2005 but currently moribund, and to expedite Sweden’s entry into NATO. Rekindling relations with Washington would also be a focus. Erdoğan’s strong man persona went down well with Donald Trump, but US policy makers have grown increasingly irked at Türkiye’s direction and Biden has kept Erdogan at arm’s length. US Ambassador Jeff Flake met with Kılıçdaroğlu in April, infuriating Erdoğan but indicating the US would be keen to reset the bilateral relationship.

An opposition victory in the election is far from assured, and there will be some elements of foreign policy that remain unchanged even under a Kılıçdaroğlu presidency. Nonetheless, a new government in Ankara would be likely to act to dampen tensions, and bring an end to the combativeness that has marked Turkish diplomacy in recent years.