The US cybersecurity firm Mandiant recently issued a fresh warning about an ongoing influence campaign comprising a network of thousands of inauthentic social media accounts. According to Mandiant’s qualitative and circumstantial observation-based investigation, the campaign that the firm has named “Dragonbridge” supports China’s political and strategic interests. Dating back to 2019, the campaign initially focused on discrediting the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. However, in the years since, the focus has shifted and the agenda has expanded. Recent activities suggest that the campaign is now targeting developments in the rare earth elements domain, where Australia, the United States, India and Japan (the “Quad” countries), as well as Canada and others, are looking to establish supply chains.

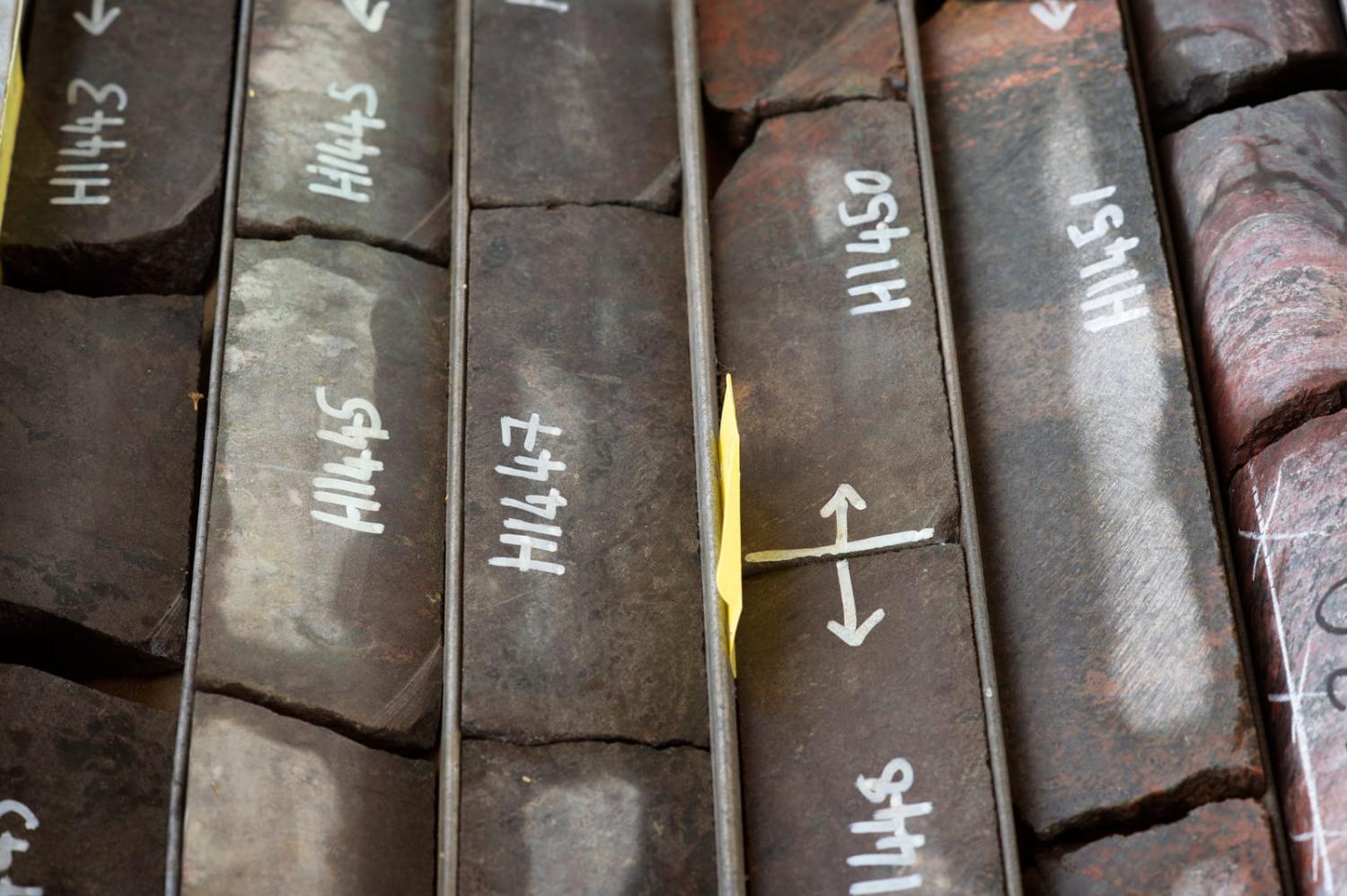

Broadly defined, rare earth elements exist in unrefined caches in several places around the world. Including lithium, cobalt and more than a dozen others, these elements are vital components for everything ranging from smartphones, television sets and electric vehicle batteries, to drones, communications equipment, stealth technology and missile systems.

While countries such as India, the United States and Australia have large deposits of rare earth elements, it is China that leads the world in both production and processing capabilities by a huge margin. In 2021, China’s production as a share of global output was around 60 per cent, trailed by the United States with around 15.5 per cent, Myanmar with 9.4 per cent and Australia with 7.9 per cent. China has only about a third of the world’s known reserves but as much as 85 per cent of processed rare earth elements come from China.

This near monopoly in rare earth elements processing provides China with huge geopolitical leverage. While several countries have mining capabilities, the processing operations are capital intensive, require high-tech know-how and are environmentally sensitive. As other countries remain dependent on China for their end-product needs, Beijing has sought to pressure its adversaries and competitors by controlling the rare earth elements trade. This was visible in 2010 during tensions over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute between Japan and China, and again during the recent US-China trade war under the Trump administration.

As Beijing thwarts supply, the shortage can result in price rises and delays in strategic projects critical to national security. For years, China has worked towards building an integrated rare earth elements ecosystem, encompassing every aspect from mining to end-product manufacturing, while either strategically acquiring competitors or running them into the ground by flooding the market with cheaper products, crashing prices, and making them unprofitable.

Today, a consensus to establish China-resilient rare earth elements supply chains has emerged among several nations. This is especially important for the Quad partners as each are producers and consumers, while aiming to establish considerable processing abilities. Further, as competition in the Indo-Pacific warms up, rare earth elements will be critical for establishing defence capabilities.

The recent Mandiant warning highlights that the Dragonbridge campaign has morphed to target rare earth element-related companies from Australia, Canada and the United States. The aim has been to shape the political, environmental and social narratives in countries that are either looking to establish rival mining capacities or processing capabilities.

According to Mandiant, the campaign has targeted the Australian mining company Lynas Rare Earths Ltd with content making allegations about its environmental record. The campaign has involved calls for protests against Lynas’ planned construction of a processing facility in Texas by posting from accounts masquerading as Americans and locals. The Dragonbridge campaign had already attempted to sway public opinion in Malaysia where Lynas operates processing facilities, with allegations about rare earth elements operations leading to radioactivity and calls to boycott the company.

Similarly, the campaign has also targeted the American company USA Rare Earth and Canadian miner Appia Rare Earths and Uranium Corp. Negative messaging linked with Dragonbridge has been observed during the announcement of potential or planned rare earth elements production and/or processing activities by these companies. Accounts peddling these claims have been noted on numerous websites and social media platforms, and in more than a dozen languages.

India is in a complex position. The country is endowed with the world’s fifth-largest reserves of rare earth elements, but almost no processing capability and an increasingly strained relationship with China. In recent years, India has looked to establish indigenous defence and high-tech industries under a vision for self-reliance “Atmanirbhar Bharat” as set out by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. A guaranteed supply of rare earth elements will be essential to this mission.

Indian Rare Earths Limited is a government-owned corporation with a monopoly over India’s extraction processes. However, its focus has remained on providing critical minerals for India’s atomic energy programs and not typically on broader activities. This has led to the situation where India supplies its mined rare earth elements to other countries, such as Japan, which processes them for use in end products, while India imports processed rare earth elements for use from China.

The Quad has a working group on supply chain security for rare earth elements. Since 2020, India and Australia have also moved towards strengthening partnerships in the rare earth elements domain, with the hope India can benefit from Australia’s technical know-how and experience in processing operations, while Australia can benefit from establishing market demand and economies of scale.

However, in this context, fear of a Dragonbridge-like campaign has emerged about disinformation that could adversely mould public opinion. It’s an exquisite irony – a fight online about the very materials that are crucial elements of the digital age.