Australia’s Director-General of Security, Duncan Lewis, has published his urgings in support of a bill before the federal parliament to impose obligations on communication service providers to facilitate investigative access to encrypted communications.

Formerly, such a public participation by the head of the domestic anti-espionage and counter-terrorism agency in political debate about a proposed legislative reform would be unusual, to say the least. Nowadays, it is to be welcomed. This latest example is an important contribution to a significant political controversy, all the more so given the perspective provided by his position.

We would not tolerate executing a search warrant on one person’s residence by destroying the neighbour’s.

As the minister in the responsible portfolio of Home Affairs, Peter Dutton has been reported as suggesting that the Opposition should support the bill in order to be on the side of the security of Australians. Understandably, shadow attorney-general Mark Dreyfus has maintained the critical role of testing and scrutiny of the bill, including its salient details.

In principle, Lewis is putting forward a very persuasive case, with which I agree. But it does not follow that the present bill should simply be waved through by the Opposition or Senate cross-benchers. In particular, both technological and civil libertarian grounds for doubt about the proper balance to be struck in achieving appropriate access to putatively nefarious communications, should be the object of much more critical thinking than Dutton apparently wishes to be directed to the question.

It seems everyone serious about the matter accepts that the authority of a warrant is a necessary safeguard, especially before accessing the content of communications. Care should be taken to avoid any weakening of that orthodox, historical, and practical protection. Lewis fairly clearly lines up with this approach. In this regard, the attitude of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation in its post-Hope Royal Commission character continues to accord with what I observed as to the embrace of such values by ASIO officers when I was Independent National Security Legislation Monitor from 2011 to 2014.

The policy that ought to be enacted must proceed on the basis of principle. Changes in technology are not apt, in themselves, to throw up new matters of principle, let alone to qualify or abolish important values advanced by established principle.

Advances in metallurgy, for instance, or the cunning of locksmiths did not alter, nor should they have altered, the principles concerning warrants to search private residences for material relevant to criminal investigations. And the fact that the reasonable force necessary and therefore appropriate for the execution of such an ordinary search warrant may have called for more violence when a door is both fortified and expensively locked, could not possibly justify doubt as to the principle at work.

That principle is, simply, that civilised society can justify on proper occasions the destruction of personal privacy and the security of a home. I cannot recall any serious argument against search warrants authorising the smashing down of a door upon refusal to open in the face of a warrant. Contemporary legislation aimed at preventing or overcoming the fortification of bikies’ headquarters is merely a recent example of centuries old social expectation.

Eavesdropping, colloquially, has a bad name. That reflects our visceral revulsion against the violation of the privacy of conversations, especially at home. But societies like ours have never hesitated to provide officers of the law and official investigators with the means covertly to listen in on conversations, or to read private documents, and in secret, when the occasion justifies it. So long as occasions are justified by law and by properly regulated actions in compliance with the law, there can surely be no sensible objection.

Privacy or confidentiality have never been seen as importing some kind of privilege against private or confidential communications being available to lawfully authorised investigators or officers of security agencies.

It would be too silly for words to assert that public murderous statements could be examined by police, but not secret plotting to accomplish lethal ends. And I guess there is little effective espionage conducted in the open.

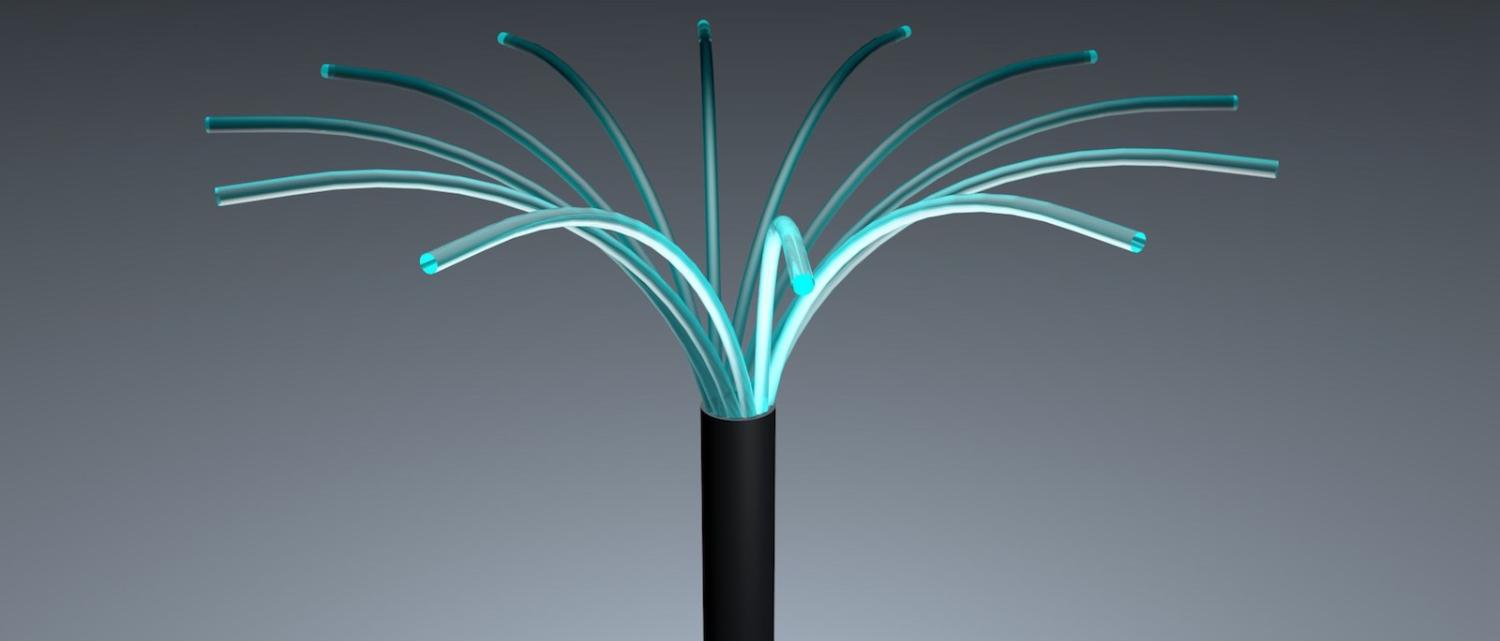

And so, why should we jib at providing means lawfully to authorise access to encrypted communications, as opposed to communications generally? What is it that could, in principle, render an encrypted communication inappropriate for access to be given to our protective and investigative agencies, while unencrypted communications have long been available in accordance with enacted authorisation and safeguards?

Oddly, in the current debate into which Duncan Lewis has fortunately ventured, it seems to me that some voices have been raised in favour of the encrypted character of the communications as the reason why access should not be given to these public officers. That is absurd.

Encryption could not possibly be seen as a mark of innocence, let alone by comparison with a lack of encryption. If anything, and too much should not be made of this at all, secrecy – that which encryption seeks to protect – is more likely to be associated with communications that one or both of the parties to it would prefer not be revealed either to the public, or to persons who may criticise the content, or even be alerted by it to possible wrongdoing. This is just common sense.

We would not tolerate executing a search warrant on one person’s residence by destroying the neighbour’s. If the current bill poses that kind of threat, all the more reason for Mark Dreyfus and his colleagues to insist on the speed of enactment being deliberate, not precipitate.

But we would not listen to a superior locksmith arguing against the general notion of search warrants authorising the breaking down of doors. Encryption of telecommunications should not have or import any more privilege than flash metalwork.