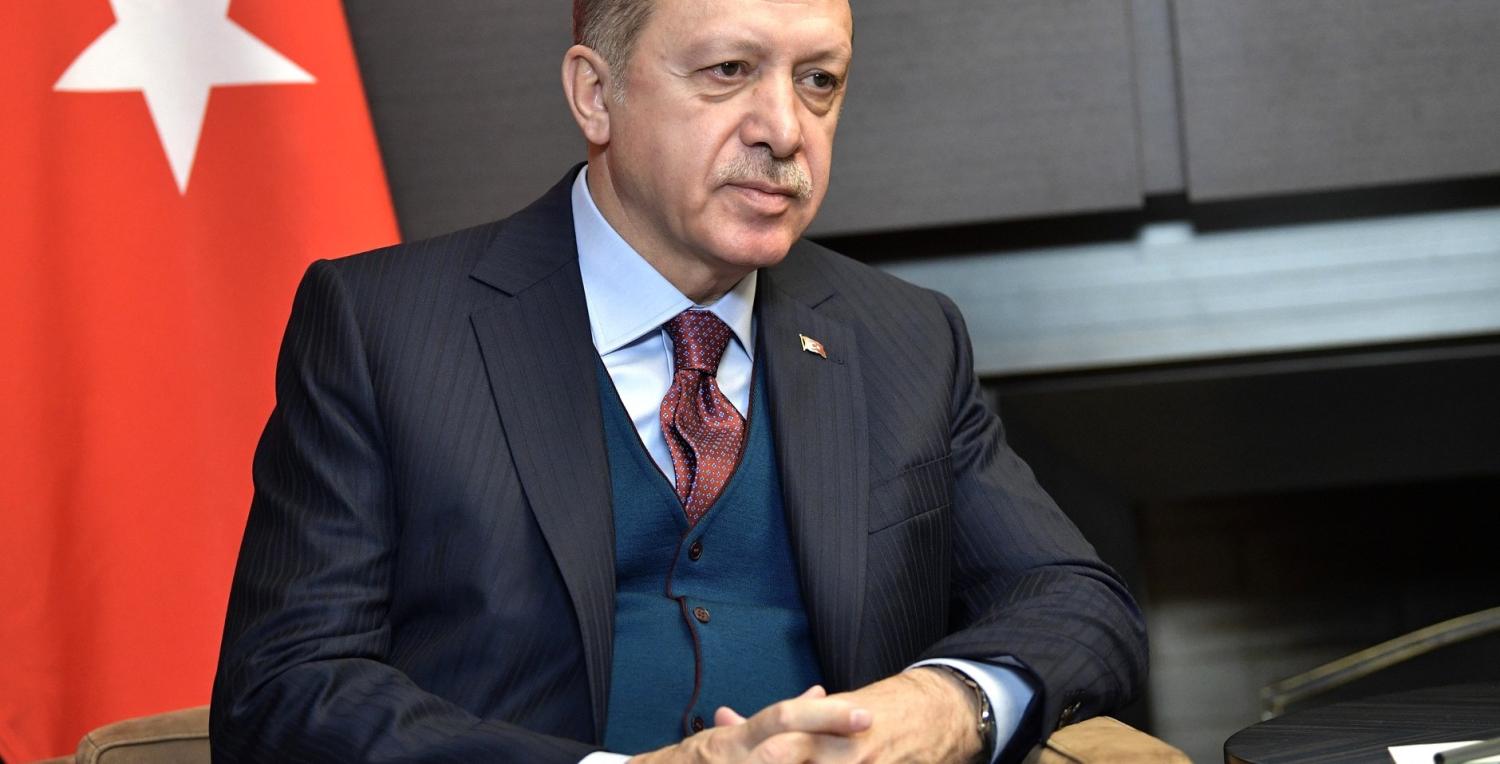

Turkish President Recip Tayyip Erdogan did not mince his words after news of a US-backed Syrian Border Defence Force (SBDF) emerged. The SBDF would consolidate numerous militia groups in Northern Syria, including the predominantly Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG), into a unified and modernised military structure. Erdogan was outraged, claiming Ankara would 'crush' any US 'terror army' and 'strangle' the force 'before it's even born'.

Erdogan's soundbites are usually directed to a domestic audience, and his threats are frequently empty. In the past, his hawkish rhetoric has targeted a range of actors, including the US, Russia, Israel and Germany; yet these threats rarely align with action. Over the past decade, foreign powers have come to understand that there is a usually a difference between Erdogan's public persona and his private, more pragmatic one.

But this recent outpouring was exceptional in its directness. Although the simple interpretation is to view Erdogan's remarks as part of his increasing megalomania, it's better to analyse his reaction as a symbol of anxieties about Turkey's regional decline.

These concerns have been fuelled by inconsistent US foreign policy and Ankara's struggle to decipher Trump's crude populism. This includes Trump's reckless and destabilising approach to NATO, which has weakened Erdogan's oft-repeated tactic of launching into hyperbole while protected by Europe's security architecture.

Furthermore, Erdogan's enthusiasm for Trumpian foreign policy (which was initially interpreted as less critical of his authoritarian tendencies) faded quickly. First, Ankara's backchannels were tainted following the arrest of occasional Turkish interlocutor and former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn as part of the ongoing Russia scandal. Second, the clumsy announcement of the Jerusalem Embassy move meant Erdogan was forced to admonish Washington publicly – a large risk given Trump's reactionary nature.

Turkey has attempted to counter this inconsistency by forging stronger ties with Russia, but Ankara should be wary of Moscow's shallow enticements. For instance, visible signs of security cooperation, such as the acquisition of a Russian S-400 missile system, are tokenistic and self-destructive in comparison to the long-term value of the NATO security umbrella, despite Trump's recent disdain for the organisation.

Perhaps more presciently, Moscow's and Ankara's interests clash more than they align. Moscow has been steadfast behind Assad in spite of protests from Erdogan. In contrast, Ankara has backed the Free Syrian Army which might best be described as a force for 'moderate extremism', stripped of ISIS's worst excesses and broadly supportive of the Turkish vision of governance.

Vladimir Putin and Erdogan's well publicised post-2016 'bromance' also neatly forgets that Turkish rebels openly fight Russian loyalist forces on the ground in Northern Syria. Should Assad's troops prevail (which is looking more and more likely), Turkey's importance to Russia would lessen rapidly as Moscow consolidates its strategic warm-water port in Tartus.

China too has a strategic eye on Syria, with implications for Turkey. While Turkish–Chinese competition has been increasing steadily over the past decade, violence in Syria has provided Beijing with a convenient way to establish a presence in the region. Hence Beijing is now incorporating Damascus into the wider Belt and Road Initiative, diversifying its routes into both Europe and Africa at the expense of Turkey's traditional geographical pivot.

Given this geopolitical context, the formation of the SBDF would be a vivid symbol of Ankara's decreasing regional influence.

Contrast the current situation with that of the mid-2000s. Then, Turkey viewed itself as heir to the regional order, enjoying strong relations with Europe and the US, and was the model government for countries engaged in the Arab Spring. Now, in 2018, Turkey finds itself as an afterthought of great power politics. It is struggling to protect the integrity of its own southern border. Its alliances are increasingly fleeting. It faces the establishment of a de-facto Kurdish buffer state with formidable military power, backed by the US, blocking its route of influence into the wider Middle East.

Together, these conditions leave Turkey in an undignified position, where the best option is to launch a renewed offensive against YPF forces in a last-ditch attempt to raise the political and economic cost of US support for the SBDF.

There is a certain irony to all this. Kurds, who would make up the majority of the SBDF force, have been framed by a long succession of ideational entrepreneurs as the key threat to the Turkish state. This cartoonish vision of the Kurds as saboteurs helped consolidate a national identity and important reforms following the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire.

But now the overuse of hyperbole, combined with a misreading of the geopolitical environment, has accelerated Turkey's decline and increased the likelihood of a permanent Kurdish military capability on the country's border. Consequently, when Erdogan states that he would 'crush' any US 'terror army', he should perhaps re-examine the broader dynamics at work, asking why such an army might emerge, and to what extent he is responsible for its making.