Sometimes, watching the latest news, Europe’s last war comes to mind. At this time 30 years ago, the conflict in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the deadliest chapter in the violent break-up of former Yugoslavia, had settled into a static phase. After more than a year of rapid territorial offensives and population displacements, neither side now seemed able to gain the upper hand.

As in Ukraine, the conflict had first erupted when the leader of a larger, neighbouring state had justified his army’s intervention through the assertion of cultural and historical tenure, supporting the formation of a breakaway state-within-a-state. By mid-1993, media coverage had begun to wane, but missile and artillery strikes continued against urban centres, inflicting destruction on historical buildings, schools and markets, killing hundreds of civilians including children in a series of heart-rending atrocities. At this level, the reporting from Ukraine seems depressingly familiar.

The Bosnian war has dimmed in the global collective memory. But the people of that region, and many who now call Australia home, still remember it starkly. Australia has hosted large communities from former Yugoslavia since the historic influx of displaced Europeans after the Second World War, and by the early 1990s a second major wave was underway. In the decade after 1992, almost half the 100,000 people entering Australia as refugees or humanitarian migrants were from former Yugoslavia, especially Bosnia.

I was working in the region as an Australian diplomat at the time, and there was considerable interest at Canberra headquarters in my reporting. The Australian government was a conscientious contributor to international deliberations about the conflict, and a significant financial supporter of the international agencies that were working to support traumatised people across the region.

There are limits to any comparison between the Bosnian and Ukrainian conflicts. None of the Bosnian protagonists had access to nuclear weapons, nor were any of them permanent members of the UN Security Council. The cultural differences between Catholic Croats, Orthodox Serbs and Muslim Bosniaks find no comparison in today’s Ukraine.

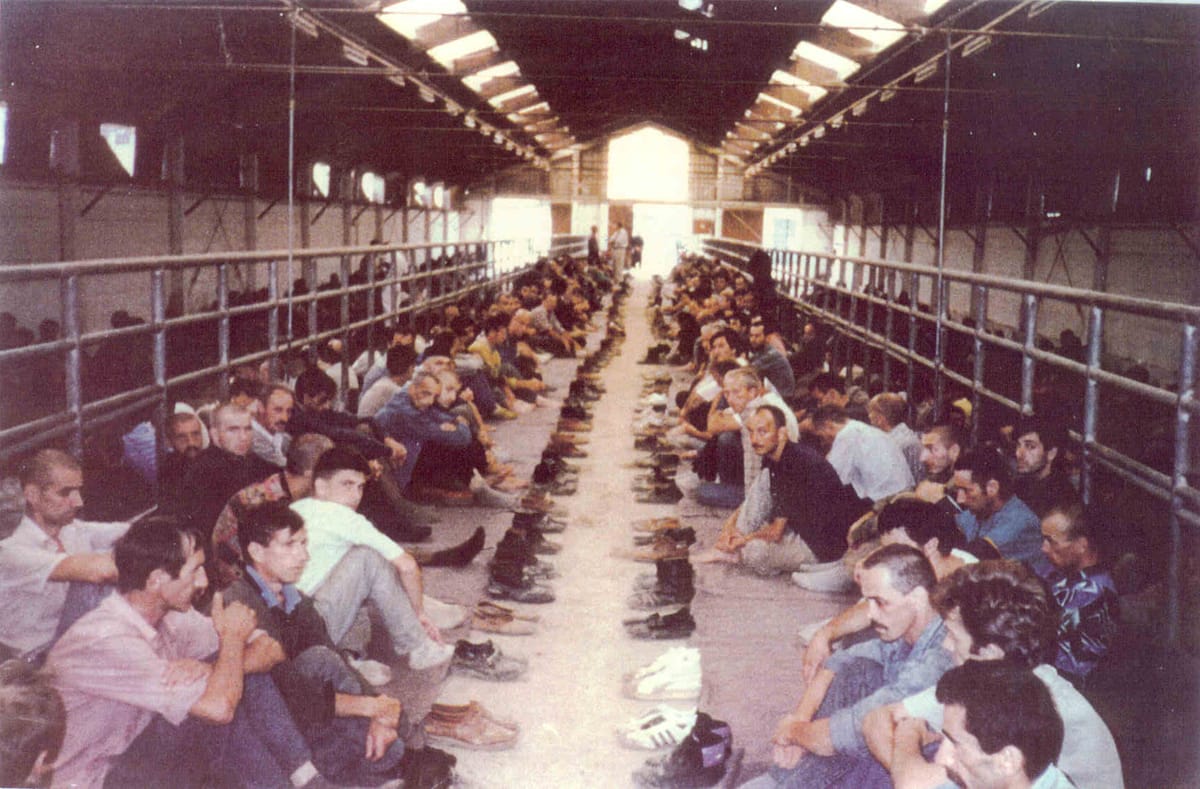

The Bosnian conflict was sparked by the Muslim-led Sarajevo government’s declaration of independence from Yugoslavia in 1992. The underlying causes of that nation’s violent disintegration were both specific and highly complex, lying deep in the troubled history of the Balkan region. The Bosnian Serbs, supported by the rump Yugoslav regime of President Slobodan Milošević in Serbian Belgrade and the Serbian-dominated Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), responded by seizing swathes of Bosnian territory for ethnic Serbs. This led to counter-offensives by the others, and “ethnic cleansing” entered the international lexicon as people on all sides were expelled from their ancestral homelands.

The war in Ukraine is a reasonably clear-cut story of unprovoked Russian aggression against a smaller neighbour. Wagner Group chief Yevgeny Prigozhin was probably channelling the views of other informed Russians when in June during his short-lived mutiny he called the lie on the claim that NATO provoked it. (His fate will discourage others from repeating this view aloud any time soon.) It is not as straightforward to cast any one faction as the only villain in Bosnia. All sides committed at least some atrocities. The extremism of Serbian ethno-nationalism was fully matched on the Croatian side. The Bosniaks are commonly described as the principal victims, and at some stages came under attack from Serbs and Croats alike. But they were tarnished by association with the brutal Muslim “foreign fighters” who joined their cause, some of whom went on to plant sleeper terrorist cells in western Europe and launch the September 11 attacks in the United States.

Similarities can be found between Milošević and Vladimir Putin, with their impassive authoritarian styles, their suppression of political and press freedom at home, and the correlation between their respective pan-nationalist visions of “Greater Serbia” and “Greater Russia”. They also seem to share some disturbing personality traits. Putin seems to have no remorse for his decisions and their impact on innocent people. He also fails to acknowledge, let alone accept responsibility for, negative outcomes. As for Milošević, he was described as follows by Warren Zimmerman, the last US Ambassador to Yugoslavia:

He is a man of extraordinary coldness. I never saw him moved by an individual case of human suffering; for him, people are simply abstractions … This chilling personality trait made it possible for Milošević to condone, encourage, and even organise the unspeakable atrocities committed by Serbian citizens in the Bosnian war. It also accounts for his habitual mendacity.

It’s interesting to reflect on the overall trajectory, over time, of the international response to the 30-year-old Bosnian conflict as we consider what might come next for Ukraine. There is concern today that the global community’s resolve will wane as international donor fatigue sets in, and that the temptation will grow to push Kyiv into a peace settlement that rewards the aggressors and leaves war criminals unpunished. There are other wildcards in the mix, including the outcome of the next US presidential election.

But the Bosnian case tells us that the trajectory of international resolve can shift in the other direction – that global patience with the aggressors can actually grow over time. We can find some hope that if the atrocities against Ukrainian civilians continue to mount, global leaders will feel they have no option but to strengthen their support for Kyiv, and that determination to bring war criminals to justice might harden.

When the Bosnian war first broke out, the international response looked more like Ukraine 2014 than Ukraine 2022. It laid bare the weakness of the hubristic new international order that had been heralded after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The United Nations went so far as to impose an arms embargo on all parties, cementing an imbalance between the Bosniaks and the JNA-backed Serbs. The United States and Europe attempted various kinds of impotent shuttle diplomacy, just as they did when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. A UN Protection Force was deployed in Bosnia to impose stability but had limited powers and was regarded with contempt by the various factions.

But by about this point 30 years ago, the relentless brutality of the war had begun to stiffen international spines. In March 1993, the UN Security Council agreed to establish a no-fly zone over Bosnia, and NATO fighters shot down Serbian aircraft violating this arrangement in February 1994. As that year progressed, NATO and UN forces launched military operations against a range of Serb targets.

But the real turning point came another year later. In the wake of the Srebrenica massacre of 8000 Bosnian men and boys in July 1995, and deadly mortar attacks against Sarajevo’s main market in August, NATO launched widespread airstrikes against Bosnian Serb positions, with robust UN artillery support. This sharpened response ultimately forced the Serbs to join their Bosnian and Croat counterparts for peace talks in Dayton, Ohio. In November 1995, the United States hammered out a power-sharing arrangement which, while fragile, remains in place almost three decades later.

Meanwhile, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was established under the authority of the UN Security Council in May 1993, becoming the first international war crimes court since the post-Second World War Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals. It would continue to operate for 24 years, allowing victims to bear witness to the horrors they had experienced and bringing war criminals to justice.

Justice even caught up with Slobodan Milošević, the serving head of what is generally recognised as the principal aggressor state. Early in the conflict, the international community seemed intimidated by Milošević. Like Putin, he kept his negotiating cards very close to his chest while conducting secret warfare, leaving the sense that he had plenty more left up his sleeve. Most observers accepted that there was an underlying substance to this projection – just as they often have with the Russian leader more recently.

Over time, however, it became increasingly apparent that Milošević, pictured right, was not some master chess player after all, and the foundations of his power came to look more and more shaky. He was ultimately forced to resign the presidency in 2000 by demonstrations over a disputed presidential election, and he was arrested the following year by a successor administration for corruption, abuse of power, and embezzlement. The new regime then agreed to extradite him to The Hague to stand trial for war crimes. Milošević angrily refused to accept the authority of the court and died of a heart attack in his prison cell while his trial was still underway.

While the International Criminal Court has issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin, curtailing his freedom of international movement, it’s very hard to see a scenario in which a post-Putin Russia would surrender a former president to an international tribunal. There’s still some room for hope that the trajectories of these two men will ultimately be similar. Milošević’s reputation as a master strategist, and his apparently unassailable position at home, progressively came unstuck in the face of an increasingly robust response from the international community, military setbacks, and growing discontent at home.

Right now, Putin seems to be in an indomitable domestic position – Prigozhin is gone, other critics have been rounded up, and the Russian economy is holding up better than expected. But Prigozhin’s removal probably won’t remove internal tensions in Moscow, and Putin’s reputation has undoubtedly taken a dent in recent times – people may be cowed, but Russian concerns about the conflict in Ukraine are unlikely to diminish over time.

And like the rest of us, Putin will continue to grow older. History tells us it becomes hard to maintain a grip on power in these circumstances.