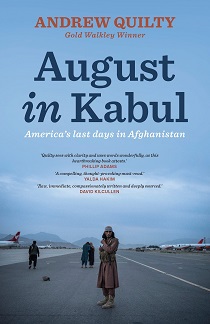

Book review: August in Kabul: America’s last days in Afghanistan, by Andrew Quilty (Melbourne University Press, 2022)

Book review: August in Kabul: America’s last days in Afghanistan, by Andrew Quilty (Melbourne University Press, 2022)

Six months after the Taliban toppled the Ghani-led Afghan government in August 2021, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine diverted the world’s attention away from Afghanistan and its dire humanitarian situation. Many Afghans – especially women – feel not only forgotten, but abandoned by the international community. Some 28 million people, or two-thirds of the population, currently require essentials simply to survive. But who pays attention to Afghanistan anymore?

As we approach the two-year anniversary of the Taliban’s return to power, it is timely to reflect on nine-time Walkley Award winner Andrew Quilty’s first book, August in Kabul: America’s last days in Afghanistan, in the context of a battle for the world’s attention.

At a recent policing conference in Sweden, I was alongside police officers from Ukraine who shared with me that some compatriots thought former comedian and actor turned president Volodymyr Zelenskyy spent too much time performing on the world stage and creating social media content, rather than attending to the critical domestic needs of a country at war.

In reviewing Quilty’s book, traversing its pages demands more time and focus than viewing a short clip of Zelenskyy’s charismatic pleas for weaponry and international support on social media. Yet August in Kabul captures pivotal insights into the complexities, contradictions and internalised tensions in the relationships that Afghans had to navigate not only for their personal safety in the Republic’s final days, but also in their struggle to build what they believed would be a better Afghanistan prior to 2021.

August in Kabul is an intense read. Had I not been working in Afghanistan on security sector reform in the months before the Taliban takeover, early sections of the book would have been more challenging to grasp, especially references to security institutions that Quilty reels off as though readers have at least a basic understanding of these structures. Accounts of desperate efforts to reach Hamid Karzai International Airport while trying to avoid the Taliban’s roadblocks – and possible execution – make for gripping reading and I found the book hard to put down in the latter half.

While security sector experts may revel in some of the masterful insights, the real value of Quilty’s book lies in the vivid accounts of key characters and their challenges connected to the decades-long political turmoil, its impact on contemporary Afghan lives and the panic in August 2021. Portrayals of these experiences largely come from Quilty’s interviewees, including Hamed Safi, a government media relations officer; Hamdullah Mohib, the country’s former national security adviser; Arman Malik of the Afghan National Army; and Nadia Amini, a 19-year-old student.

Quilty treats readers to a close-up look at what his central characters did to preserve their lives while trying to escape – or at least others’ memory of it – given their presumed prospects of death. For example, Mohib gathered precious family heirlooms for his children’s inheritance, while journalist Najma Sediqi bought a knife and spoke of preferring to kill herself rather than be killed by others, a way for a woman to retain some sense of dignity in death.

Quilty clearly spent extensive time with his protagonists, delving deep to elicit recollections, bringing a more coherent narrative around how they came to be in Kabul in August 2021. This is especially clear with Nadia, whom he met on the street amid the chaos to evacuate. Quilty visits Nadia’s childhood memories, unravelling her story about how her eight-year-old younger brother, Hanif, over the proceeding decade or so, exerted more and more control over her life, becoming a principal agitator in the family responsible for shrinking her space to exist in the world.

Readers get a front row seat to the way the men in Nadia’s family restricted her access to education, viciously assaulted her (as her mother watched on), kept her house-bound, led her to attempt suicide, and nearly transacted her to be a Taliban wife – justified on the basis that it would protect the remaining family members from Taliban harm. A crucial contribution of Quilty’s meticulous storytelling is how he makes evident that resistance to patriarchal control – even if unobservable to outsiders – still exists in women’s minds beyond the reach of men’s clutches.

Quilty demonstrates the uncertainty of the international assistance that contributed to the collapse of the government (which Zelenskyy similarly seeks to avoid), quoting an Afghan lieutenant general who said, “We were part of their [the United States’] morning plan, but not their afternoon plan”. So, while some Ukrainians may loathe Zelenskyy’s khaki theatrics, the risk of falling off stage and out of view of global leaders may be a far bigger risk if Ukraine is going to survive as a state.

While simply reading August in Kabul is hardly the activism required to support the survival of a starving population and end the further encroachment of gender apartheid, it will create indelible insights, memories and awareness among its readership from which future actions may spring.