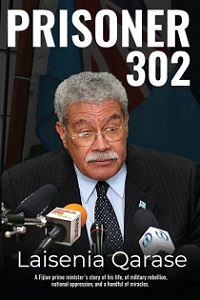

Book review: Prisoner 302: A Fijian Prime Minister’s Story of his Life, of Military Rebellion, National Oppression and a Handful of Miracles, by Laisenia Qarase (2022)

Book review: Prisoner 302: A Fijian Prime Minister’s Story of his Life, of Military Rebellion, National Oppression and a Handful of Miracles, by Laisenia Qarase (2022)

The collective mood across Fiji’s capital Suva could have been a jubilant scream. A new prime minister and government was confirmed last year on Christmas Eve, yet the euphoria was more about breaking free from two oppressive decades led by military-backed men whose currency was fear.

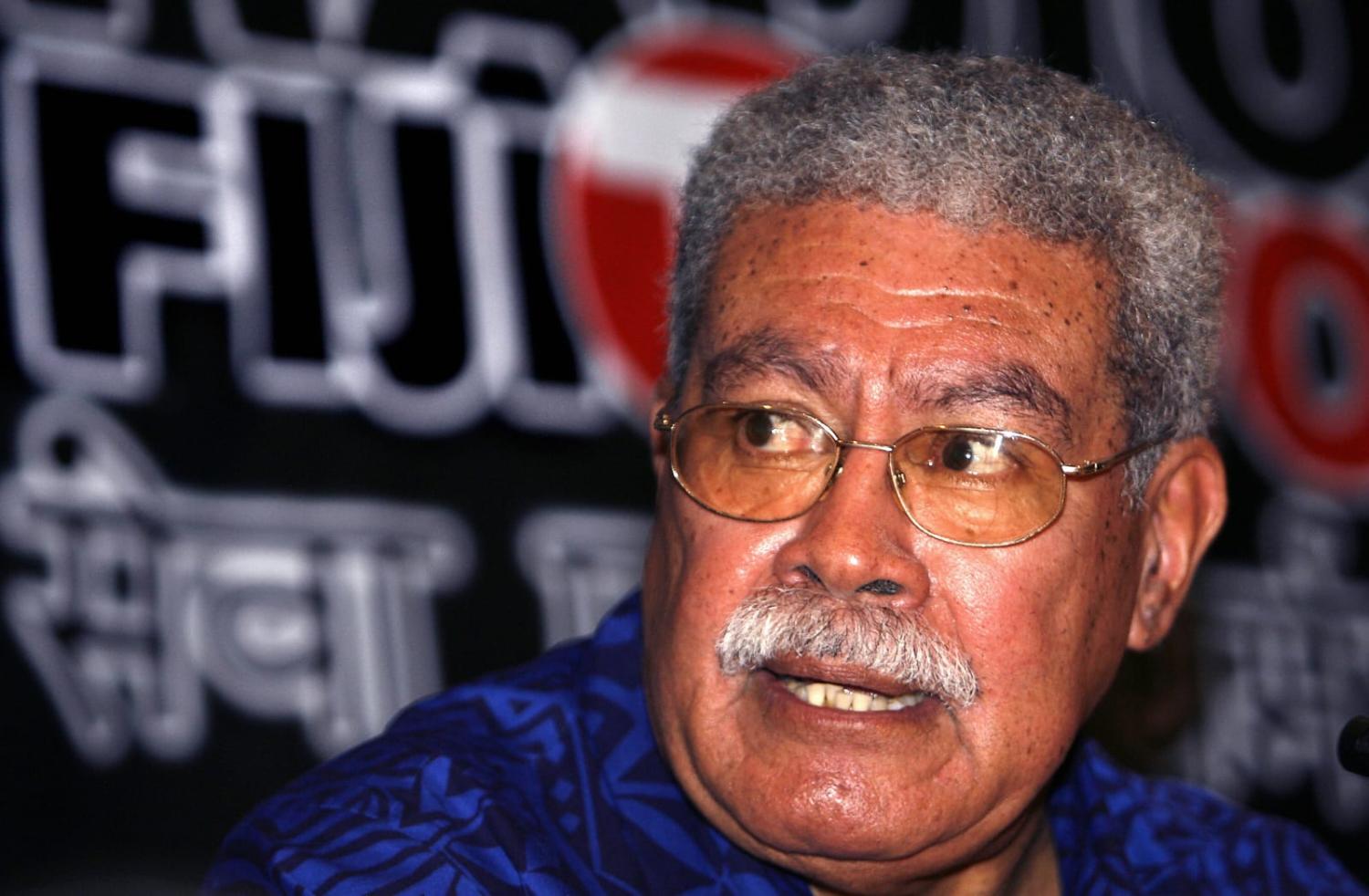

For the family of Laisenia Qarase, the banker who was forcefully removed as Fiji’s prime minister in 2006, the return of democratic rule was two years too late. Qarase died in April 2020.

Fiji’s political trajectory as a young Pacific nation struggling with its heterogeneity has attracted labels such as “coup-coup land” and “banana republic”. Since Fiji’s independence from the British in 1970, the country has had more than ten general elections since 1966, two coup d’états in 1987, one in 2000 and another in 2006.

The years after were grim, marked by grief for the people murdered without much recourse for families, for the suffering inflicted by vindictive bullies who hid behind the protection of armed bodyguards, and for the activists who carry lifelong scars from brutal beatings for speaking truth.

Qarase was in many ways a face of this indignity. Stripped of his prime ministership, he was humiliated, his head shaved before he was stuffed in an orange, numbered prison uniform. Qarase tells of this agonising experience in his posthumously published memoir, Prisoner 302: A Fijian Prime Minister’s Story of his Life, of Military Rebellion, National Oppression and a Handful of Miracles. Published a couple of weeks before Fijians went to the polls in December last year, the book is an essential contribution to understanding how Fiji traversed the darks days. For those who lived through this period, the book should probably come with a warning on the potential to re-live trauma. Yet it also offers within its pages a warning to protect the joy of a returned democracy.

In 2000, it was the failed businessman George Speight who staged a coup, days from facing fraud charges in court. Qarase, a career civil servant and a banker, was asked to be the interim prime minister. In 2001, Qarase led his party to a win in national general elections. But by December 2006, no one was surprised when military commander Voreqe “Frank” Bainimarama made real his pronouncements that he would remove Qarase as prime minister. This set Fiji on a path to dictatorial rule, a time when expressing an opinion could cost you your life.

Qarase, in writing the micro view of his personal experience, offers the macro view of a nation: Prisoner 302 is not only Qarase’s story, but also Fiji’s story.

“Our independence of action began to agitate Bainimarama,” Qarase reflects on his time as leader. “[Bainimarama] was angry and affronted by it. In his mind, he should’ve been controlling me.”

The extent of that controlling aspect was perhaps not fully appreciated by Fiji’s neighbours. The book features disturbing themes, of deplorable violence, details of torture, physical assault and verbal abuse. Methods designed to humiliate and break spirits, acts meant to scar and warn, bullying that inculcated deep distrust. Those tortured included chiefs, priests, artists, media personnel, businessmen and academics including the late Brij Lal.

As Fijians, we lost a piece of ourselves over 16 years of Bainimarama’s rule. The mental exhaustion of self-censorship was perhaps the most personal of all consequences. Prisoner 302 is however a gift to young Fijians for whom dictatorial rule was the “norm”. Qarase’s memoir is a corrective to the intentional attempt to create an alternative historical and national narrative in the last 16 years. The rights of the people, particularly children, to be exposed to different perspectives, and choose how they feel about them, should never again be compromised. The horrid media decree used by the military to censor newsrooms was this week repealed.

Prisoner 302 emphasises the importance of Fijians writing their own stories. Whatever our politics, we owe ourselves this gift of hindsight.