The Report, directed by Scott Z. Burns. Opens 14 November in Australia.

More than a century ago, the US invasion of the Philippines turned from a supposed act of liberation into a war of insurgency and operational confusion. Desperate to uncover plots, the Americans took to extreme measures. Indiscriminate violence, torture, and massacres became routine.

A US Senate committee investigated allegations of war crimes, eventually producing a 3000-page report on its findings. Several US officers were court-martialled.

President Theodore Roosevelt, an ardent proponent of US imperial aspirations, came to regret the actions exposed in numerous testimonies. Speaking in May 1902, Roosevelt said:

Determined and unswerving effort must be made, and has been and is being made, to find out every instance of barbarity on the part of our troops, to punish those guilty of it, and to take, if possible, even stronger measures than have already been taken to minimize or prevent the occurrence of all such acts in the future.

The future, as it turns out, had other plans.

Ninety-nine years later, the 9/11 attacks uncorked deep emotions in a country accustomed to war on its own terms. The invasion of Afghanistan followed swiftly, supported by a vast majority of the American public. Less than 18 months later, in March 2003, the George W. Bush administration launched a war on Iraq, sold on a hodgepodge of dubious claims.

It’s no spoiler to say nobody has faced charges for participating in the torture program, which held at least 119 detainees between 2002 and 2008, and subjected 39 to “enhanced interrogation”.

A secret memo issued by President Bush in February 2002 declared that “the war against terrorism ushers in a new paradigm”. Detainees were classified as unlawful combatants to skirt the Geneva Conventions. Suspects were whisked off to detention in Gitmo, or black-hooded into “extraordinary rendition” sites across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

Many Americans knew what was happening, despite the legal chicanery. The May 2004 exposure of torture at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq prompted a war crimes lawsuit against Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, but the denial (or defence) of torture rolled on.

In an August 2014 press briefing, President Barack Obama said, “Even before I came into office, I was very clear — that in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, we did some things that were wrong. We did a whole lot of things that were right, but we tortured some folks.”

What forced this confession was the release of the Senate Intelligence Committee Report on CIA torture, a 6700-page deep dive into the US treatment of detainees, classified but for an executive summary made public.

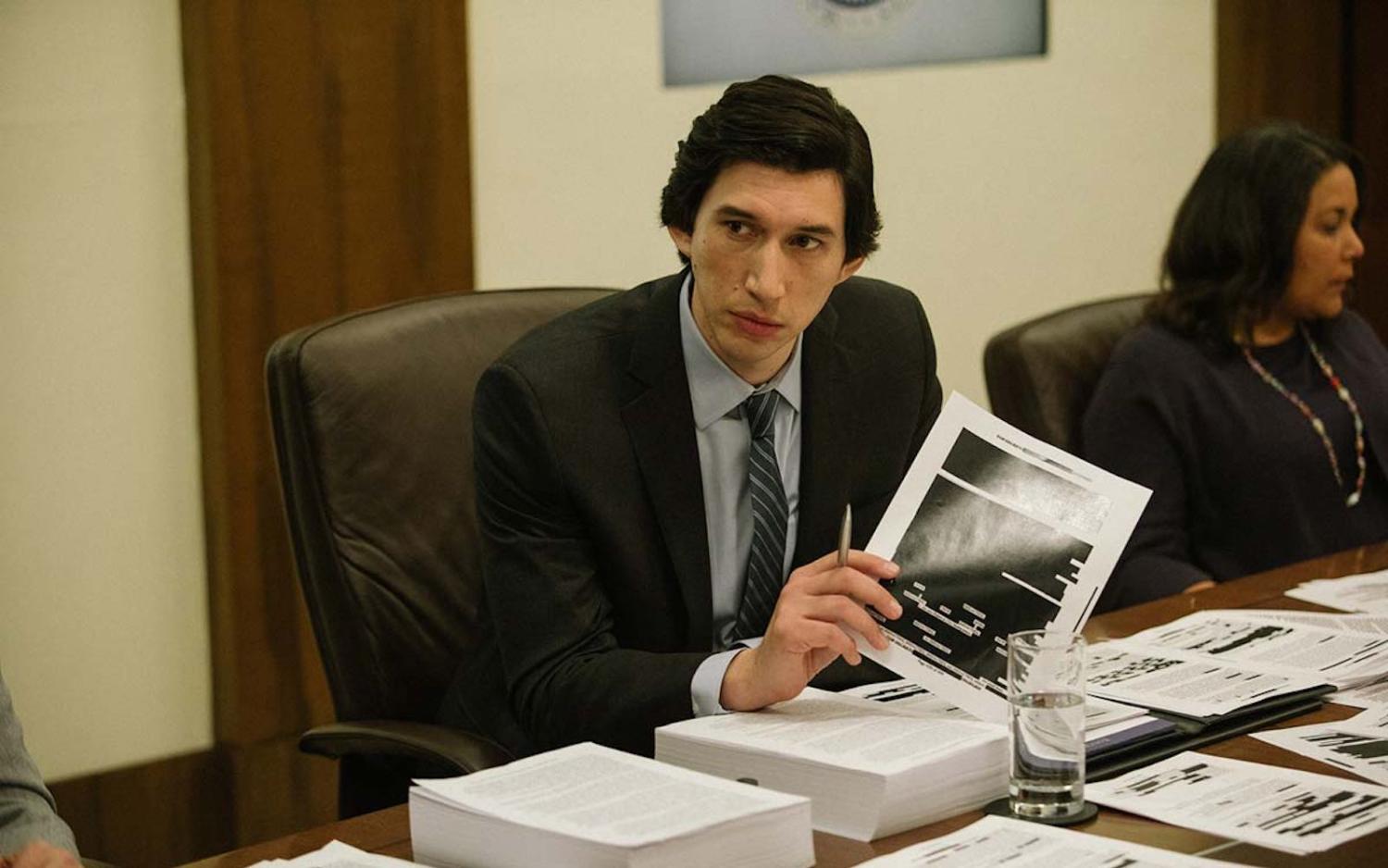

The Report is an attempt to dramatise the origins of this document, the work of a driven researcher and his Senate sponsor. Chalk it up to Hollywood ingenuity that this story can be squeezed into a two-hour thriller.

Daniel Jones, a staffer working for Senator Dianne Feinstein, is assigned to investigate the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program. The CIA destruction of 92 videotapes of interrogation sessions eliminated key evidence, with the claim that the Senate committee never requested it – although the committee never knew the tapes existed. Jones (played by Adam Driver) is given a secure office in a CIA building somewhere in the Beltway, a bunker of Soviet-level austerity filled with a few desks and eventually a few colleagues, where they will spend the next several years reading through millions of pages of documents.

Jones’ early encounter with FBI investigator Ali Soufan serves as a moral compass. Soufan explains there is only one method of interrogation that works: rapport. (He knows whereof he speaks – his 2011 book The Black Banners provided rare insight into al Qaeda and the intelligence missteps ahead of 9/11.)

The antithesis of Soufan’s method is found in the duo of James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, who pass themselves off as psychologists and experts at inducing “learned helplessness”. Their techniques – such as facial holds, forced nudity, waterboarding, and water dousing – became the basis for “enhanced interrogation”. They dismiss the need for Arabic speakers, for building rapport with suspects, even the need for experience as interrogators, of which they admittedly have none. Their methods start appearing in the film like nightmares, scenes of men bound, naked, blasted with deafening death metal, while anonymous goons wail at them, “Where is the next attack?”

Convinced by their own snake oil (for which they were paid more than US$80 million), Mitchell and Jessen come off as cartoon villains – except, of course, they are actual people.

Feinstein, played with supreme poker-faced restraint by Annette Benning, provides Jones the cover to keep digging. As chair of the Intelligence Committee, she has the clout to keep the hounds at bay – many, of course, would bury the whole episode – but it is her composed scepticism that forces Jones, time and again, to make the case for further investigation.

Meanwhile, a New York Times reporter appears periodically as the serpent of temptation, offering Jones the easy out of telling the secrets that may never get out otherwise. That, however, is a different movie, and Jones informs him he is going to do this “the right way”.

For all his obsession, Jones’s motivations are never quite clear. When the report is finally released, a projectile lobbed in the turf battle between the Senate and the CIA, Jones is suddenly without a rudder.

It’s no spoiler to say nobody has faced charges for participating in the torture program, which held at least 119 detainees between 2002 and 2008, and subjected 39 to “enhanced interrogation”.

American enthusiasm for torture was stoked in the aftermath of 9/11 by shows such as 24, with its ticking time-bomb fantasies and gloves-off heroics. Once the domain of sadistic villains, torture became the good guy riding in to save the day. The producer of 24 called it “a patriotic show”.

Except there was no ticking time bomb. The torture didn’t work – it just broke people and broke the rules. It may have been cathartic entertainment, but what did it solve in real life?

The Report is not about torture or justice. It’s a hero’s journey into a political hell. Jones delved into its ugliest depths and walked away. Whether he won or lost is a matter of perspective.

What has been lost, however, is the notion that the United States is a nation capable of upholding its highest values even in its lowest moments. That compromise is a slippery slope, and today it’s plain to see how far that slide can go.

The Report may be cathartic entertainment, as well, but it can’t undo what’s been done.