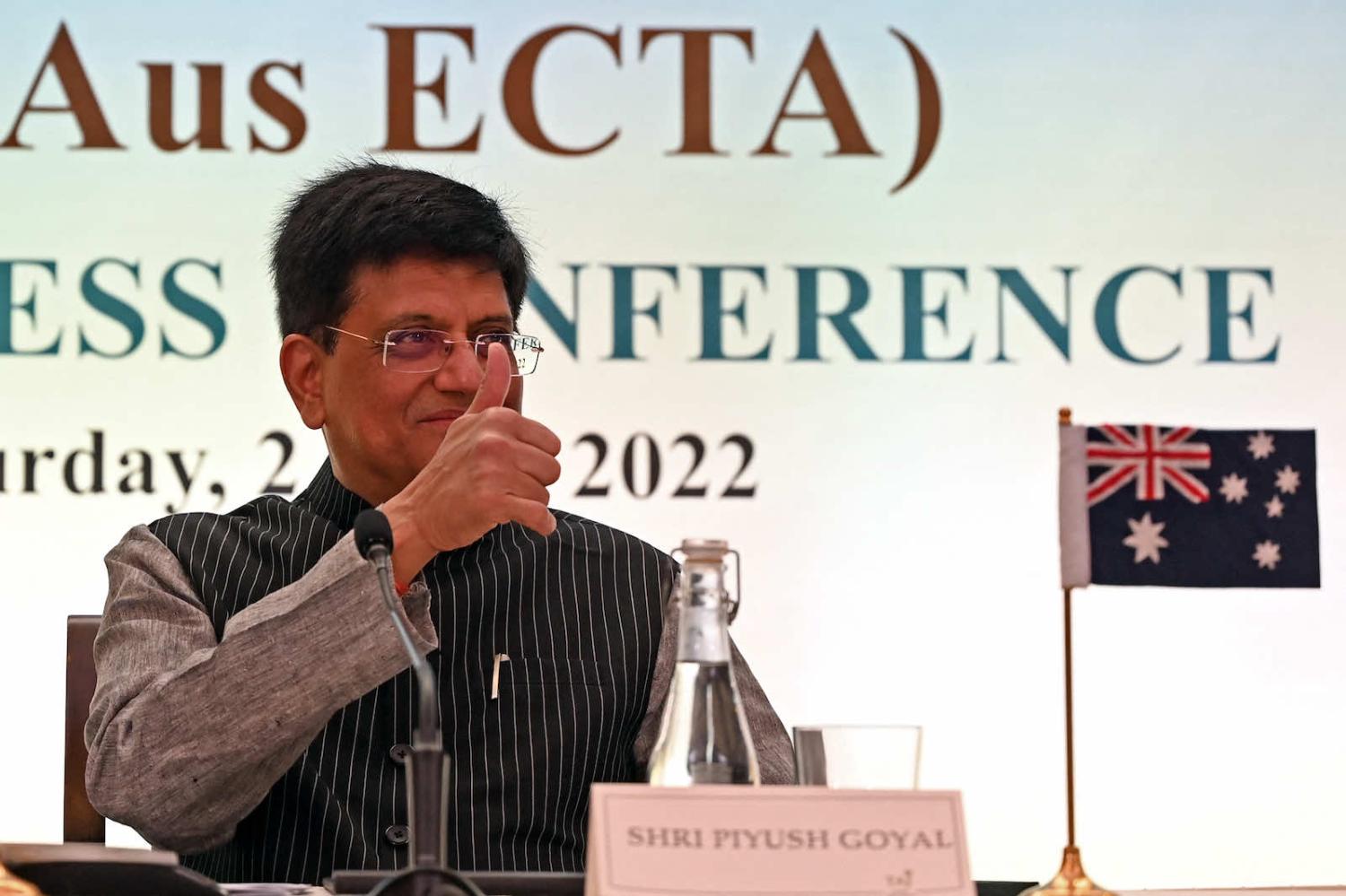

The Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (AIECTA) signed on 2 April marks a first for India in terms of liberalisation of “substantially all” trade and timeline of negotiations.

India has often been blamed for prolonging trade negotiations with its rigid stance on tariff liberalisation and mode-4 concessions in the services sector. Negotiations towards free trade agreement (FTA) between India and Australia were initiated in 2011. However, the deal was put on the backburner following the release, in 2018, of an “India Economic Strategy 2035” prepared by former diplomat Peter Varghese for the Australian government. The report, while having identified India’s economic potential, was despondent about the possibility of a comprehensive economic cooperation agreement with India in the light of differential negotiating positions of the two economies. The conclusion of AIECTA in 2022 within months of announcement of revival of discussions, is therefore a definite departure from the past for India.

The ease with which the recent rounds of negotiations have been concluded further reveals deft commercial diplomacy and flexibility on part of both countries. For Australia, India is an attractive alternative market for its goods when trade relationship with its lead partner economy, China has become difficult and restricted. AIECTA provides Australia with preferential access to the Indian market through reduced tariffs for over 85 per cent of tariff lines including, for the first time, conditional reduction in tariffs on wines.

In return, India has been granted tariff free access to over 95 per cent commodities in the Australian market with immediate effect for most commodities. As the base tariff on many of these commodities is five per cent, there is a reasonable preferential margin for Indian exporters.

Furthermore, phasing out of tariffs, where applicable, is to be completed in 5, 7 or 10 years. Careful consideration has been accorded to Indian sensitivities. Large number of agricultural commodities and dairy sector have been excluded and imports of lentils, almonds, cotton and some fruits will be subject to a tariff-rate quota. Furthermore, India has achieved some success in its mode-4 negotiations with an allowance for temporary movement of select category of professionals.

However, it needs to be recognised that this is only an interim deal and there are significant challenges to achieving a complete and comprehensive agreement. It may be worth mentioning that India’s only other attempt at a limited “trade in goods” agreement with Thailand in 2003 has not culminated into a full free trade agreement even after 19 years of the framework agreement having been announced.

India needs policy reform within in order to successfully negotiate the comprehensive economic agreement with Australia.

While it may be true that the interim AIECTA has a much broader goods coverage relative to the India-Thailand early harvest scheme, it is also true that Indian goods may not find it easy to increase their share in the Australian market which is currently dominated by China. In labour intensive sectors such as leather goods, footwear and apparel products, for example, while India is among the top exporting nations to Australia, China’s share is substantially higher. Even Vietnam is ahead of India with a larger share of Australian imports in sectors such as footwear. Both Vietnam and China have preferential access to the Australian market through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and China–Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) respectively.

Overcoming the competitive hurdle, while being a priority for India to be able take advantage of this deal, may not be immediately possible. This is significant given that limited benefits in terms of increase in Indian exports or increased trade in favour of the partner economy have been among the many reasons cited by India for not joining the RCEP as well for India’s recent call for a review of its FTAs with ASEAN, South Korea and Japan.

More importantly, the desired comprehensive deal, will require India to deal with the thus far “difficult issues” that may include, apart from opening up of sensitive sectors such as dairy, questions of data ownership, localisation and privacy related to e-commerce. In addition, in the context of investment liberalisation, which has been completely left out of the interim deal, India will have to review its 2016 model bilateral investment treaty and fine tune provisions such as on investor-state dispute resolution and make it balanced and comprehensive as per global best practices. In respect of both these issues India has had difficulty negotiating at the multilateral and regional levels. India therefore needs policy reform within in order to successfully negotiate the comprehensive economic agreement with Australia.

If one assumes that the fresh wave of India’s FTAs is occurring against the backdrop of the country staying outside the RCEP so far, then, to achieve the kind of gains that RCEP membership may have offered in terms of manufacturing competitiveness through participation in regional value chains, it is necessary for India to move swiftly to complete the comprehensive deal with Australia along with requisite domestic policy reforms.

There is no gainsaying that only a comprehensive economic partnership between India and Australia can truly contribute to strengthening the economic pillar of the Indo-Pacific.