We’re asking contributors to put together their own collected observations like this one – and as always, if you’ve got an idea to pitch for The Interpreter, drop a line via the contact details on the About page.

October marked the sixth anniversary of the murder of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia. For many years, Galizia had, through her often uncompromising journalism, campaigned against widespread corruption in the small island nation of Malta.

She was blown to pieces by a remotely activated bomb believed to be set by contract killers at the behest of still unknown individuals. She was 53.

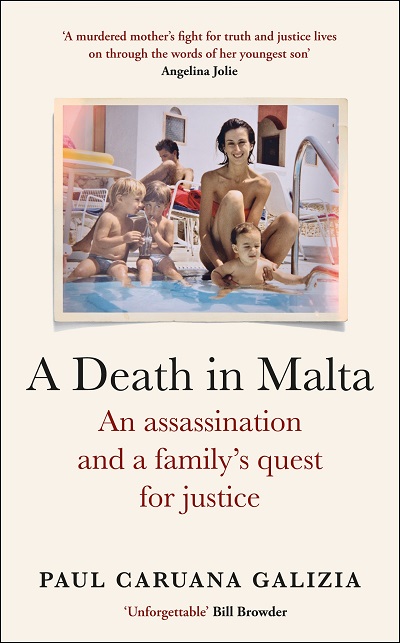

The heartbreaking task of chronicling her work and death has now been assumed by her youngest son, journalist Paul. His account, A Death in Malta: An assassination and a family’s quest for justice, is a gripping reminder of the value of the free press and the continuing importance of the profession of journalism.

In evidence given to an inquiry established by the Council of Europe, Galizia described how she had been targeted for three decades. This included arson attacks on her home, the freezing of her bank accounts, and dozens of criminal and civil libel suits being brought by government ministers and businesspeople, as well as misogynistic, dehumanising and abusive attacks online and in the street. She was branded a “witch”.

Like so many tin-pot authoritarians, local oligarchs seized on the licence that US President Donald Trump’s then newly minted “fake news” offered them to avoid public accountability.

After a hard fight, Galizia’s friends and supporters persuaded the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe to require Malta to hold an inquiry into her murder under the European Convention on Human Rights.

The public inquiry found that the Maltese State had “created an atmosphere of impunity, generated from the highest echelons of the administration inside Castille, the tentacles of which then spread to other institutions, such as the police and regulatory authorities, leading to a collapse in the rule of law”.

Despite all this, Paul Galizia concludes that there has still been no unequivocal acceptance of the horrors that his mother faced, let alone an unequivocal apology for it, from Malta. Nor, all these years later and despite four convictions of low-level hit men, have all the suspects in her murder been brought before a court. Four more face trial. Meanwhile, the Maltese State continues to preside over endemic corruption and fundamental structural failures.

The family’s UK counsel, Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC, summarised the position perfectly at the memorial service held to mark five years since Daphne’s assassination: “whilst that climate of impunity festered in Malta, the world stood idly by. The UK and other countries across Europe ignored what was happening under their noses, and left Daphne to her fate.”

Europe is not immune from horrific attacks on journalists. On 21 February 2018, just four months after Galizia’s murder, a young Slovak journalist, Jan Kuciak, and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová, were assassinated in their home. Kuciak worked as a reporter for the news website Aktuality.sk, investigating tax fraud allegations against businessmen with connections to top-level Slovak politicians. Despite the arrest and conviction of the assassins, the principal suspect was acquitted.

An alliance of press freedom groups said: “This case follows an all-too-common pattern in which the hitmen and facilitators involved in such crimes are put behind bars while the suspected masterminds who ordered the murder evade justice.”

Paul Caruana Galizia’s short and compelling book should be compulsory reading for all students of journalism and government. Daphne signed her last ever blog with the prescient words, “There are crooks everywhere you look now. The situation is desperate.”