Ahead of a visit to Australia last month, Timor-Leste’s President Jose Ramos Horta sought to play the China card, raising the possibility of asking Beijing to finance the Greater Sunrise gas project in the Timor Sea. This project has been central to the rather tenuous Australia-Timor-Leste economic relationship for well over a decade after Timor-Leste first expressed its hesitations about plans to pipe gas to Darwin, instead preferred to develop the Tasi Mane industrial zone on Timor-Leste’s southern coast.

How credible is Horta’s “threat” and how likely is it that China will step in to finance this project?

We have been comparing Chinese development finance in Timor-Leste to that of traditional development partners. It would seem unlikely that China would finance this project but with a strong caveat. China does have commercial interest in Timor Leste, where its state-owned enterprises are investing in major connectivity and energy infrastructure projects – this does add some credibility to Horta’s claims.

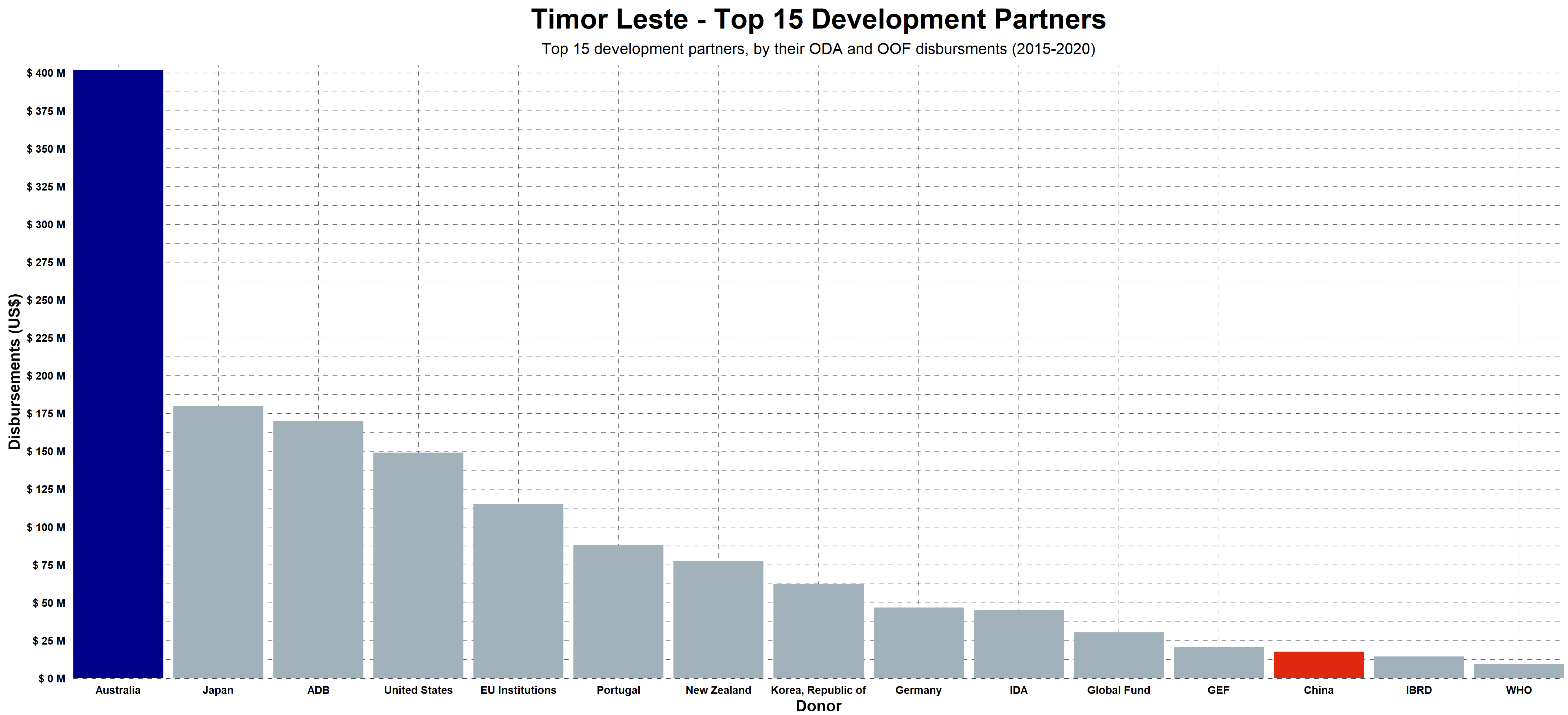

As far as development finance is concerned, our preliminary findings suggest that China is a minor donor as aid and development finance partner to Timor-Leste. Compared to other development partners, Chinese aid projects, that we define as being supported by China’s largest policy banks or the government itself, accounts for one per cent of total development finance flows to the country, making China the 13th largest donor in Timor-Leste.

In contrast, Australia remains the largest aid donor to Timor-Leste based on actually disbursed aid. In fact, Australia provides more aid than the next two biggest donors (Japan and the United States) combined. Australia far outstrips China when it comes to aid and development financing in Timor-Leste in almost every sector, as China mainly provides in the health and education sectors. Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong has pushed back on Horta’s requests related to Greater Sunrise as she maintains that Australia wants to push for an economically resilient Timor-Leste through Australia’s aid program in the country.

However, plainly outspending China does not necessarily make Australia the winner in this geo-economic competition. Questions remain about the political salience of Australia’s aid – while it is focused on human development, it is not fulfilling the energy infrastructure needs that would earn Canberra political currency in Dili.

China’s aid and development finance flows to Timor-Leste seems unlikely to increase dramatically given the economic slowdown and the financial difficulties it faces at home.

China’s commercial interest in Timor-Leste, however, does add some credibility to Horta’s claims. China’s state-owned enterprises are financing three major connectivity and energy infrastructure projects – Suai Highway, Tibar Deep Sea Port and Timor-Leste State Grid. While not supported directly by the Chinese government or its policy banks, these projects do highlight China’s commercial interest in Timor-Leste. Such investments do raise the question about the blurred lines between Chinese development finance and the commercial activities of Chinese state-owned enterprises. While these projects are not financed by the government or policy banks, they are connected to Tasi Mane, which would not be viable if the Greater Sunrise project is not built.

This does provide further context to Horta’s talk about asking China for funding, noting also that in 2019 Timor-Leste’s state-owned gas company rejected reports of seeking a $16 billion commercial loan from China’s Export-Import Bank (EXIM) – the leading financier of China’s aid and development finance in Southeast Asia – to finance the Greater Sunrise project.

The key dividing issue is the commercial viability of building the processing plant in Darwin, which is what commercial venture partner Woodside is insisting, whereas Horta is adamant that the plant be built in Timor-Leste. Feasibility studies that had stated it would cheaper to construct the plant in Darwin have now been contrasted by more recent findings that reportedly assess operating costs for the plant in Timor Leste would be $1.3 billion cheaper than in Darwin.

There is an uneasy tension between good economics and good geo-economics. Understandably, Australia has, so far, been non-committal given the commercial questions and risks involved. Similarly, China would also have to do a cost-benefit analysis of funding such a huge project amid its domestic economic and political turmoil. Would the risks outweigh the influence Beijing could obtain from signing on for this project? In a fashion, Australia and China find themselves in a similar position in calculating how to respond to Horta’s request for financial assistance.