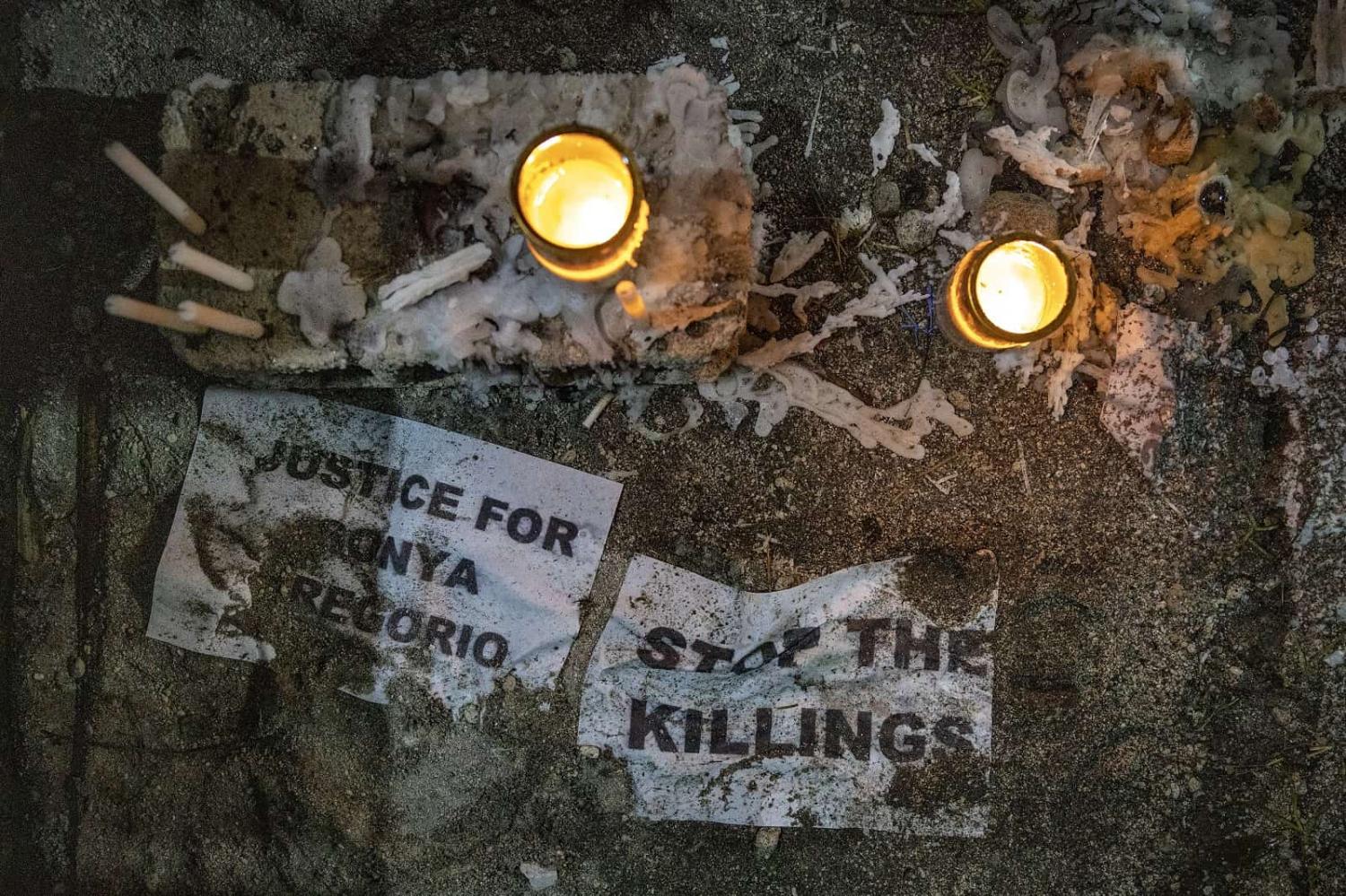

In a June resolution, the International Criminal Court prosecutor Karim Khan asked to resume an investigation into former president Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs, which was deferred in November 2021 at the request of the Philippine government. Government data has revealed at least 6,000 people were killed during anti-drug operations by the police across Duterte’s term from 2016 to 2022. But human rights groups believe that this number did not include victims of vigilante-style killings, raising the estimated toll to between 12,000 and 30,000 deaths.

Khan cited a 2022 report of the Philippines’ Commission on Human Rights (CHR), describing these deaths as the result of “excessive and disproportionate force” against drug suspects amid “a culture of impunity”. The CHR report also reaffirmed its initial findings that there is a:

“consistent narrative by law enforcers alleging that the victims initiated aggression or resisted arrest; who are mostly civilians killed in uninhabited locations sustaining gunshot wounds in the heads and/or torso; that there is non-cooperation by the police; and that there is a lack of effective, prompt, and transparent accountability mechanism to address the drug-related killings.”

The Philippine government, however, has challenged the ICC resolution, given that the country officially withdrew from the Court in 2019, the second country to do so after Burundi did likewise in 2017. Duterte made the decision to withdraw the Philippines’ membership after the ICC launched a preliminary examination into his anti-narcotics operations in 2018. According to Duterte, “the acts allegedly committed by me are neither genocide nor war crimes. The deaths occurring in the process of legitimate police operations lacked the intent to kill.” But this contradicted his previous public threats against drug suspects: “My order is shoot to kill you. I don’t care about human rights; you better believe me.” He also praised the rising body count of victims of police killings as proof of the “success” of his “war on drugs”.

The ICC, however, clarified that “it retains its jurisdiction over crimes committed during the time in which the State was party to the (ICC) Statute and may exercise this jurisdiction over these crimes even after the withdrawal becomes effective”. The prosecutor plans to investigate the drug war killings during Duterte’s presidency, from July 2016 to March 2019 (before the Philippines left the ICC), as well as incidents during his tenure as vice mayor and mayor of Davao City from 2011 to 2016.

Facing the consequences of his predecessor’s bloody legacy, newly-inaugurated President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos has opted to reiterate Duterte’s decision to withdraw from the court, categorically stating that “the Philippines has no intention of rejoining the ICC”. Though the Philippines’ withdrawal will not deter an ICC investigation, this will make it difficult for the ICC to exact cooperation from the government since the global court has no police power to support its investigation.

Marcos has also argued that: “There is already an investigation going on here and it’s continuing, so why would there be one like that [in the ICC]?” This reinforces an early pronouncement during his election campaign that: “We have a functioning judiciary, and that’s why I don’t see the need for a foreigner to come and do the job for us”. Yet the ICC’s Khan claimed that there has been no indication of “domestic authorities investigating the alleged systematic nature of these and other killings”, and described the Philippine Department of Justice’s investigation as a mere “desk review”.

Marcos’ evasion of the ICC probe leaves the impression of a political calculation and a personal discomfort towards human rights. He may be seeking to prevent antagonising Vice President Sara Duterte, a political ally, by shielding her father from accountability. And with a family history of past abuses under his father’s dictatorial regime, Marcos is predictably less concerned about upholding human rights and demanding accountability than preserving the political alliance.

More importantly, the Philippines’ non-membership in the ICC does not bode well for the country’s democratic ideals. Duterte’s decision to withdraw and Marcos’ subsequent resolve not to rejoin the Court highlights the grim reality that the Philippines’ commitment to human rights can be side-stepped and subjected to compromises depending on who is in power. The case of the Philippines also sets a precedent for other countries to leave multilateral institutions whenever state leaders feel intimidated or uncomfortable. If a long-established democracy such as the Philippines renounces the ICC, what is to hinder other countries, particularly neighbouring authoritarian states in Southeast Asia, from doing the same?