It’s a lesson in not believing exit polls, or not believing breathless hype, or listening closely to reporting from the grassroots, or all of the above.

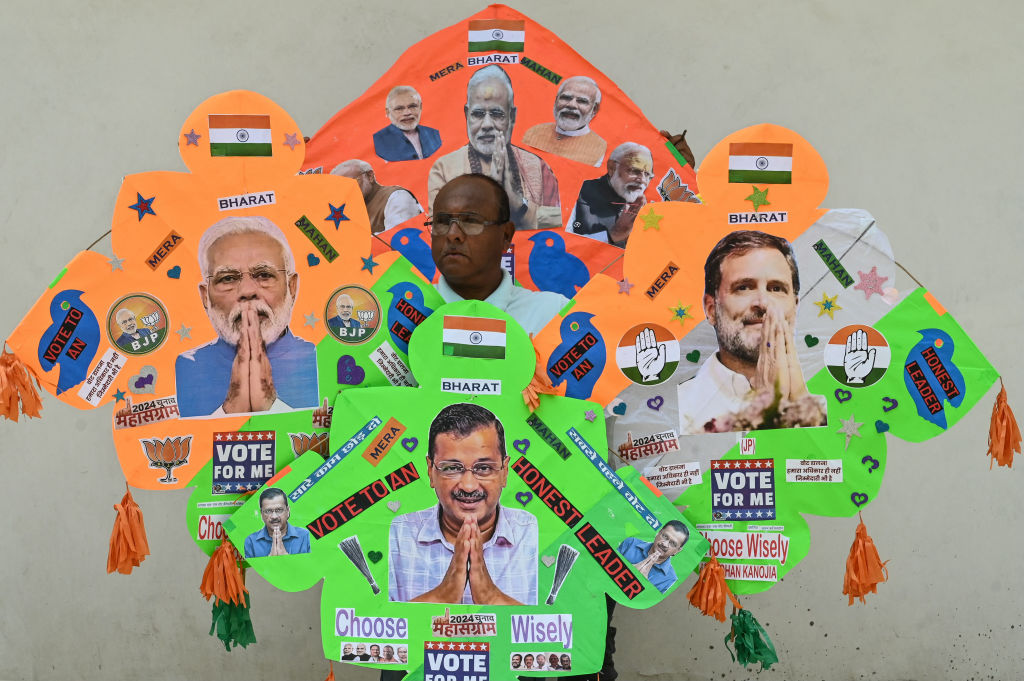

While the Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party has claimed success in India’s national elections, it is somewhat of a Pyrrhic victory, with the BJP ceding significant ground to the opposition INDIA alliance. Modi’s government has secured a third term in office – but the margin is far slimmer than expected, and it looks like the BJP won’t clinch a majority in the 543-member parliament so will have to rely on the support of coalition partners.

As prominent Indian journalist Rajdeep Sardesai tweeted: “the bigger message is this: India prefers a strong opposition to a single party, single leader dominance.” India’s proud history of anti-incumbency is back.

The impact was felt almost immediately on the markets, in particular by the Adani group, the company of magnate Gautam Adani, long close Modi, which at the time of writing had lost a combined $US45 billion on Tuesday – the biggest single-day rout ever for the conglomerate. Expectations the day before of a Modi electoral landslide had driven the shares up. Adani saw his personal net wealth also plunge by $25 billion.

With a wider lens, the Indian election result could even be seen as a vindication of liberal democratic values around the world, which is notable this year in particular.

From the voting results reported, it appears that rural India voted heavily against the BJP – although it’s worth noting that each state has its own political makeup and often localised parties. For example, the party lost power in the seat that is home to the controversial Ram Temple in Ayodhya. Elsewhere, jailed Khalistani separatist leader Amritpal Singh beat the closest candidate in his Punjab seat by almost 200,000 votes. And it appears likely that the son of the man who assassinated former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi will also win a seat in the state.

The election result can be seen as a vindication of liberal democratic values: that Indians, deep down, prefer these over an authoritarian state, no matter how charismatic the authoritarian or how loud the cheers for him. With a wider lens, the Indian election result could even be seen as a vindication of liberal democratic values around the world, which is notable this year in particular. This election result may shed more light on where global trends are headed – not because India is the only country where democratic ideals have flagged, but simply because of the timing of this poll, six-odd months before a big one in the United States.

For Australia, there are now a few things to keep watch on. Canberra is likely low-key delighted that the Modi government has been returned: virtually all of Australia’s big wins in the relationship have been under it, from the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership status in 2020, to the Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement in 2022. A new leadership may have meant rebuilding key relationships or prolonged renegotiations. For its part, India’s Ministry of External Affairs and the government appear on board with bringing Australia closer. The third term spells a degree of stability for the Australia-India relationship. However, there is always the caveat that this might be undermined if India decides to get more muscular in its foreign policy.

In Australia, it is widely known that there is a large and fast-growing Indian diaspora. (From next month, you can read writings directly from this diaspora in Growing Up Indian in Australia, which you can pre-order here). There have been some indications in recent years that the Indian government is starting to view its diaspora as a cohort of Indians that simply lives abroad, and can be harnessed for morale-influencing duties. An example is the 2022 visit here by BJP youth leader Tejasvi Surya, during which he urged the Hindu community to vote for parties that “exclusively protect Hindus”.

It is worth drilling down into some of the detail for another potential win for the Australia-India relationship: what happened in Uttar Pradesh.

The project has already had negative outcomes, such as violent clashes between Hindus and Sikhs in western Sydney in 2021. And last year, there were tensions between Sikhs and Hindus in connection with the Khalistani referendum. The election of Amritpal Singh in Punjab will doubtless give rise to escalated efforts by the Khalistani movement, and given the issue’s propensity to spill across borders, this is an issue that Australian authorities probably will want to be prepared for. Already, the government has identified domestic social cohesion in the Indian community as a major issue to contend with.

Finally, it’s worth drilling down into some of the detail for another potential win for the Australia-India relationship: what happened in Uttar Pradesh. In India’s most populous state and the so-called “cow belt”, the ruling BJP, led by Hindu monk Yogi Adityanath, widely seen as a potential successor to Modi, has lost a lot of ground to the Samajwadi Party, led by Akhilesh Yadav. The Samajwadi Party has gained 37 of the state’s 80 seats, ahead of the BJP, which has 33 at the time of writing. Yadav, from a political family, served as the state’s chief minister for five years. He also studied at the University of Sydney in environmental engineering. The connection didn’t necessarily do much for the relationship last time round, but perhaps an older and wiser Yadav in the chief ministerial office might lean into sentimentality and open the door a little wider to Australian visitors.

In coming days there will be more clarity on the formation of the ruling NDA alliance, various leadership positions – and the fate of some key leaders in particular who failed to perform well at the polls. But one thing is clear: democracy in the world’s largest democracy is as sound as it can be.

Aarti Betigeri is the editor of Growing Up Indian in Australia, which is out on July 2.