A visit to the United States this month has further added to Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s growing list of foreign policy achievements, even as his administration continues to be plagued by domestic political problems. Hosted by President Joe Biden for a state dinner on 10 April, the two leaders then welcomed Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jr the next day for a historic trilateral summit. Security issues took centre stage in both meetings: the US-Japan bilateral saw an upgrade to the partnerships command and control structure, while the trilateral summit’s joint statement made explicit reference to China’s “dangerous and aggressive behaviour” in the South China Sea while pledging enhanced maritime cooperation.

Ever since assuming office in October 2021, Kishida has made foreign policy a priority. His administration has pledged significant additional investment to the country’s defence budget, set to increase 16.5% this financial year, with further increases planned to 2027 that will see the country spend close to 2% of its GDP on defence.

Japan has also continued engage more through regional initiatives such as the quadrilateral partnership between Australia, India, Japan, and the United States (Quad) and the new trilateral cooperation between Japan, South Korea and the United States, in addition to penning numerous security-based investment deals with regional partners under its new Official Security Assistance (OSA) framework.

Kishida’s visit to the United States also produced new speculation about Japan’s potential role as a cooperative partner in the AUKUS pact, which would be another logical consequence of the country’s more activist foreign policy.

Japan’s renewed focus on multilateral engagement, while still taking place under the umbrella of the Japan-US security alliance, has rightly drawn a focus within the context of enhanced regional tensions. This extends beyond China’s increased assertiveness in the South China Sea to include the escalation in violence following the February 2021 coup d’état by Myanmar’s military, the continued security threat posed by North Korea, as well as the global hardening of strategic alignments in response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Kishida has also benefitted from willing partners. Biden has recommitted the US to internationalism, while the Marcos administration in the Philippines and the Yoon administration in South Korea have steered increased engagement with Japan. It is the potential for future shifts in the domestic political environment of participating countries that has seen the recent Japan-South Korea-United States and Japan-Philippines-United States trilaterals feature mechanisms aimed at ensuring sustainability, including clear schedules for lower-level meetings. In essence, they are designed to outlast their respective administrations, to “Trump-proof” or “Duterte-proof” regional deterrence.

Kishida is facing his own domestic political challenges. His Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has been beset by two major scandals. First, the aftermath of the assassination of former prime minister Shinzo Abe exposed deep ties between many LDP lawmakers and the controversial Unification Church. Second, a major political slush fund scandal broke in December 2023, implicating members of Kishida’s own faction (now disbanded). This has eroded public trust in his administration.

The NHK monthly poll tracking approval in the government this month sunk to its lowest figure in almost two years, with 58% expressing dissatisfaction in the administration. Other polls have public support for the administration even lower, and the LDP faces difficult by-elections at the end of the month.

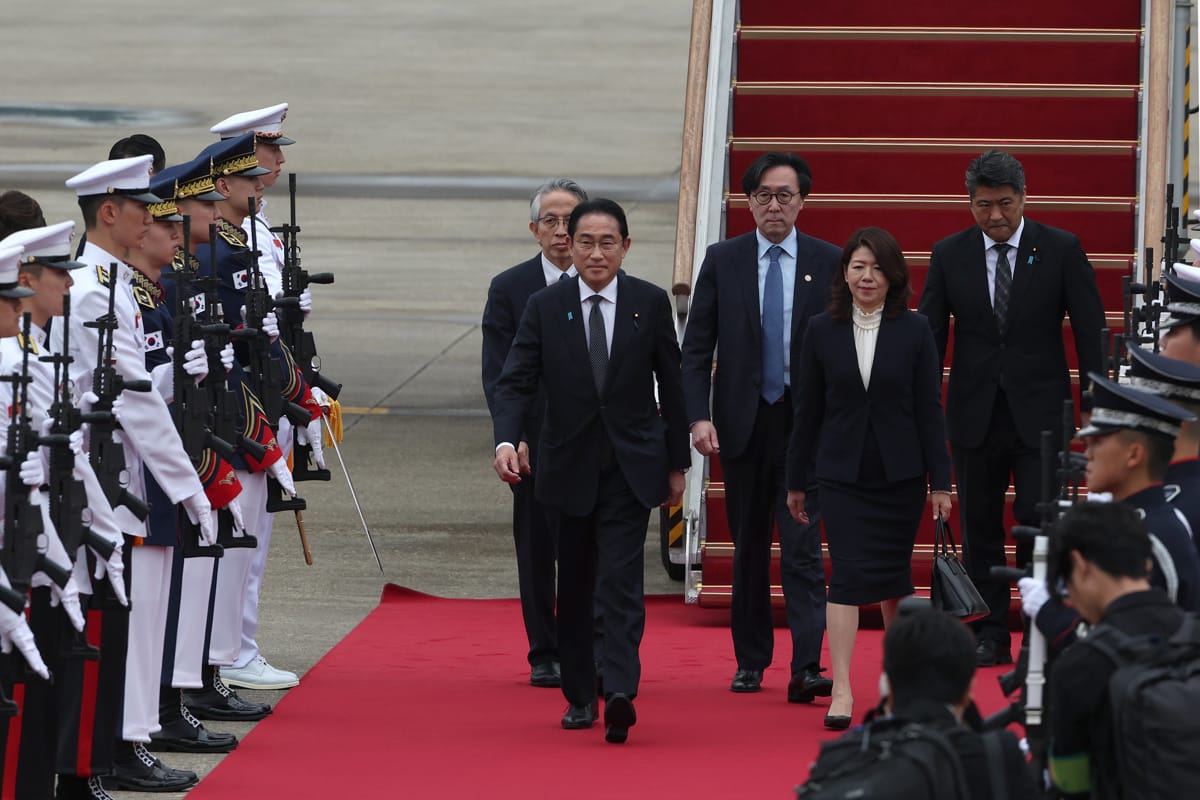

Kishida will be hoping that his foreign policy achievements, and specifically the red-carpet treatment he received in the United States, will bolster his sagging approval ratings. Ironically, it is the focus on sustainability in its recent foreign policy engagements that will put regional and international partners at ease. In contrast to a potential Trump administration in the United States, a future electoral win by a member of the Duterte clan in the Philippines, or the return of the Democratic Party in South Korea, any potential replacement to Kishida will not come with a foreign policy re-alignment by Japan.

But it follows then that foreign policy will also play a limited role in deciding Kishida’s fate. He has recently denied rumours of calling an early election in June, instead tying his political future to the internal LDP leadership ballot to be held in September. If his approval ratings don’t rebound by then, the LDP will likely decide to reset with a more palatable candidate not tainted by political scandal.

There is at least one data point in Kishida’s favour. According to the NHK poll, his approval ratings saw a sharp uptick when he hosted the G7 Summit Hiroshima in May 2023. While he might hope for a repeat following his trip to Washington, political history suggest that foreign policy will not be enough to save Kishida’s job.