While many eyes are on China’s port investments in the Indian Ocean, Japan has also been busy. The scale of its infrastructure investments in the region rivals, and sometimes exceeds, that of China.

But Japan argues that its growing presence in the Indian Ocean is qualitatively different, focused on transparency, economic sustainability, and a rules-based order that should become part of regional norms. Australia must consider the role in can play in these projects.

Compared with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Japan’s investment activities in the Indian Ocean are barely promoted, and as a result its projects often fly under the radar. This obscures the fact that Japan has been very active in building infrastructure and “connectivity” across the region.

Indeed, spending on these projects is not too different from China’s spending on the BRI, which is sometimes inflated, double-counted, or based on vague future promises.

Japan’s “Partnership for Quality Infrastructure” initiative, first announced in 2015, involves infrastructure spending, over five years, of around US$110 billion in Asia. In 2016, the initiative was expanded to $200 billion globally (including in Africa and the South Pacific).

A list of recent Japanese-sponsored port projects since 2016* (with approximate Japanese funding in US dollars) indicates just how active Tokyo has been in the Indian Ocean:

- Nacala, Mozambique – port ($320 million)

- Mombasa, Kenya – port and related infrastructure ($300 million)

- Toamasina, Madagascar – port ($400 million)

- Mumbai, India – trans-harbour link ($2.2 billion)

- Matarbari, Bangladesh – port and power station ($3.7 billion)

- Yangon, Myanmar – container terminal ($200 million)

- Dawei, Myanmar – port and special economic zone ($800 million)

Japanese projects involving the development of connectivity between the Pacific and Africa have now been rolled into its Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (FOIP). Japan’s regional strategy is essentially about providing alternative responses to China’s growing economic role in the Indian Ocean region.

American analyst Michael Green argues there is an important difference between Japanese and US strategies: unlike Washington, which often sees China’s role in zero-sum terms, Tokyo recognises that all the nations encompassed in the arc from Africa to the Western Pacific desire investment and sustainable economic development. This means it is essential they are provided with concrete alternatives.

Anxiety about China’s BRI regularly centres on concerns that Chinese-controlled port infrastructure might one day be used for military purposes. But there are other reasons to worry.

China’s approach to building infrastructure is frequently criticised as being non-transparent, non-sustainable, and exclusive. Chinese companies often construct infrastructure on a sole-source basis and then gain exclusive access to what should be common-use infrastructure. Other projects may be economically unsustainable, and host countries may be left with a major debt bill for non-economic projects.

Japan claims that its approach to building connectivity has some important differences with the BRI. Its strategy emphasises the Ise-Shima Principles endorsed by the G7, including safety, reliability and resilience, social and environmental considerations, local job creation and transfer of know-how, alignment with host country development strategies, and economic viability. The strategy also emphasises norms such as transparency and non-exclusivity.

The Japanese initiative also positions India as a key partner and Indian Ocean economic hub. This might seem obvious, but it is a gaping hole in China’s BRI strategy, which bypasses India. Indeed, it is difficult to conceive of a regional economic system that does not include India as a central player.

In 2017, Japan and India announced the Asia–Africa Growth Corridor as a joint initiative to build connectivity between the Pacific and Africa. While its financial resources may be limited, India can still play an important role. For example, Delhi used its diplomatic influence in Bangladesh’s decision to award the Matarbari port project to Japan. India and Japan may also partner in other future projects, including at Trincomalee in Sri Lanka, and potentially (subject to US sanctions) Chabahar port in Iran.

While Japan’s strategy clearly competes with China’s BRI, it does not exclude China. In fact, if strategic rivalries can be overcome, there is considerable potential for cooperation. Tokyo hopes that the principles espoused as part of its initiative will become norms for future projects in the region. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has claimed that he expected the BRI will incorporate “a common frame of thinking, and come into harmony with the free and fair Trans-Pacific economic zone”.

What does this mean for Australia?

Japan has called for its “Quadrilateral dialogue” partners to join its Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy. This is consistent with Australian efforts to maintain a rules-based regional order.

Australia is unlikely to contribute finances to Indian Ocean infrastructure projects in any way approaching the major financial resources being mobilised by Tokyo. Nevertheless, Australia can play an important role as a country with considerable expertise in infrastructure services; for example, in port design and operation. Australia also has strong credentials in “soft infrastructure”, such as training and institution-building.

But it is not only technical expertise. Australia’s participation in some projects, even as a junior partner, may also be seen as useful by some Indian Ocean countries that would prefer to involve several countries (including China) in politically sensitive projects.

Diversifying the participants in these projects could truly be a win-win for all concerned. Australia needs to consider how it can work with both Japan and China in promoting open and sustainable projects across the region.

*The date was changed following publication.

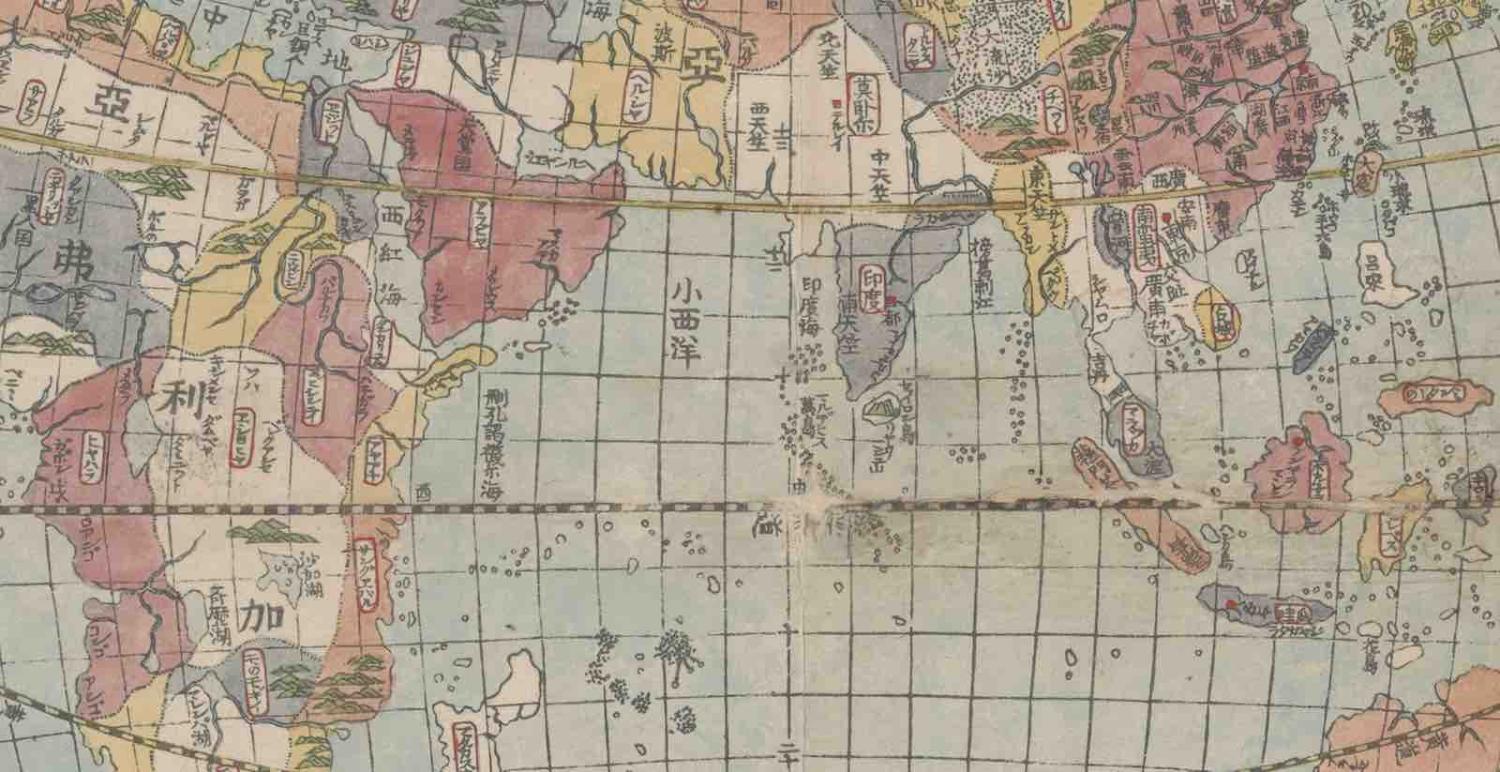

Photo via Stanford Libraries