Book review: The Future of Geography by Tim Marshall (Simon & Schuster, 2023)

Book review: The Future of Geography by Tim Marshall (Simon & Schuster, 2023)

Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot stay in the cradle forever.

~ Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, rocketry pioneer

Former foreign correspondent-turned-bestselling author Tim Marshall foreshadowed an abiding interest in outer space in his book on geopolitics, The Power of Geography. His latest, The Future of Geography, accelerates full-throttle into “space as a warfighting domain”, and his passion for the subject is clear.

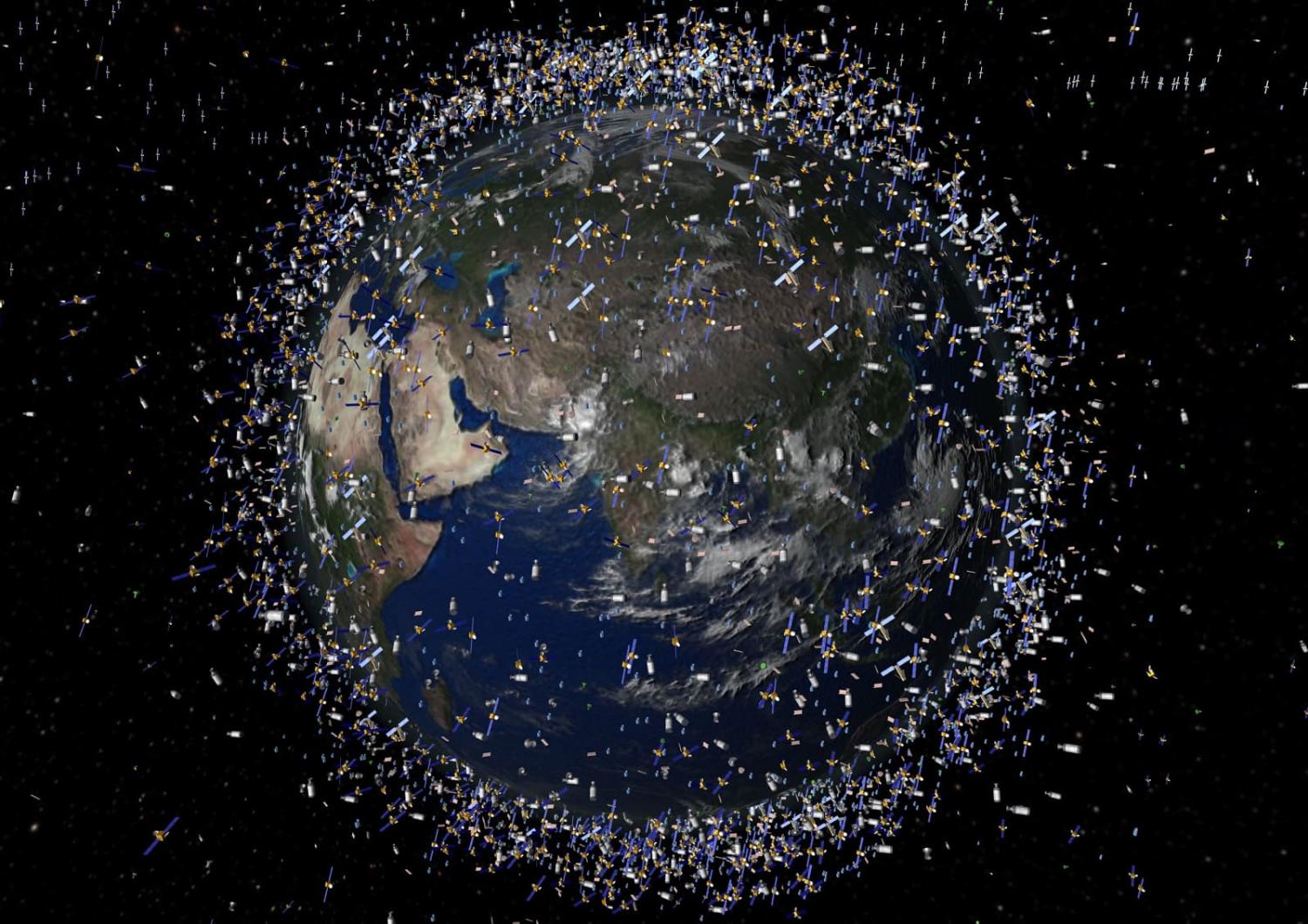

After a brief history of human-powered flight, Marshall explores the motivations of three major players on the stellar stage: the United States, China and Russia. Like Earth, “[space] has corridors suited to travel, regions with key natural assets, land on which to build and dangerous hazards to avoid.” The contest for dominance beyond the Earth’s atmosphere has shifted (slightly) from technological grandstanding during the Cold War to a combination of economic imperatives and gradual militarisation, with control of the skies above a determining factor on the ground below. Once the space-faring powers can construct and control a supply line to low Earth orbit, they can control who else can launch satellites and at what cost, and limit access to the resource-rich solar system beyond. In other words: whomever dominates low Earth orbit can shape the long-term future of humanity.

Existing laws that might otherwise govern conduct in space are outdated, vague and contested, and Marshall highlights the difficulty that could arise when the major powers confront each other (or even their allies) in space. Who has jurisdiction, for instance, if a Japanese astronaut kills a French astronaut on board the International Space Station, between modules manufactured in the United States? Can Elon Musk be considered a US proxy combatant, given his company provides Starlink satellites to Ukraine that can be used for military communications? What good is UN jurisdiction on Mars if nobody ever arrives to enforce it?

Marshall goes on to describe how other countries approach the issue. During the 1980s, France believed it was being lured into a conflict between Libya and Chad by outdated American satellite photographs. The French – no strangers to losing wars on other continents – decided to invest in a domestic satellite capability, which would later capture some of the first reliable images of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. The United Kingdom was the third country to have a secure military communication satellite, but only recently developed a domestic launch facility in Cornwall – it has mostly relied on the United States getting its satellites into orbit, in exchange for quietly hosting National Security Agency infrastructure. Israel initiated its space program in response to the failures of its terrestrial early-warning systems during the Yom Kippur War in 1973, and now launches payloads over the Mediterranean, and against the spin of the Earth, partly to ensure its space-faring vessels are not mistaken for missiles by its ever-suspicious neighbours.

Marshall also touches briefly on Australia’s own space exploits, in which he links the announcement of the AUKUS security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States in 2021 to the establishment of the RAAF’s Defence Space Command shortly after. AUKUS, of course, is focused on supplying nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, but the Department of Defence has since put out a tender for “scalable, rapidly deployable and reconstitutable” satellites as part of the necessary communications infrastructure. AUKUS also includes cooperation on electronic warfare and artificial intelligence, and the need for a more advanced satellite capability will hardly come as a surprise.

The Future of Geography is an excellent primer on space as an unavoidable (though regrettable) extension of cold geopolitical logic. It is a well-written and engaging introduction to the subject, and Marshall is ambitious for a future in which our actions in space improve the quality of our lives on Earth, rather than the length of them on a battlefield. Not all readers will appreciate the free press for Elon Musk, whom Marshall name-checks a few more times than I thought necessary.

But one figure to whom Marshall pays regular and rightful tribute is Professor Everett Dolman. Dolman’s 2001 book, Astropolitik, is a dense meditation on the complexity of strategy in space, in which “the entirety of the Earth is reduced to a single component of the total approach”. As Marshall points out, the total volume between low Earth orbit and geostationary orbit is almost two hundred times the volume of Earth, where encounters take place at supersonic speeds, and usually in the dark. The Future of Geography, then, is a cautionary tale, which amateurs and professionals alike will benefit from reading as they look up – and forward – to what follows.