Shortly after (now former) President Donald Trump incited a mob of supporters to attack the US Capitol, there was a moment in which it appeared possible that 17 Republican Senators would join their Democratic colleagues in a vote to convict Trump in an impeachment trial and bar him from holding elected office again. This potential outcome – broad bipartisan action to hold an authoritarian leader accountable – represented a long overdue but optimal democratic response to the last four years.

But three weeks is a long time in Trumpian politics, and a Senate vote this week established that only five Republicans support holding an impeachment trial at all. For those who care about the health of American democracy, it’s difficult not to feel disappointed and perhaps infuriated.

The dynamics at play are a reflection of ongoing struggles within a Republican party that either will or will not break with Trump. Whether that break occurs is outside the control of most reasonable people, so it would make sense to focus on what can be done with a new administration. Patience will be required during the pandemic, but on this front, there is reason for tempered optimism.

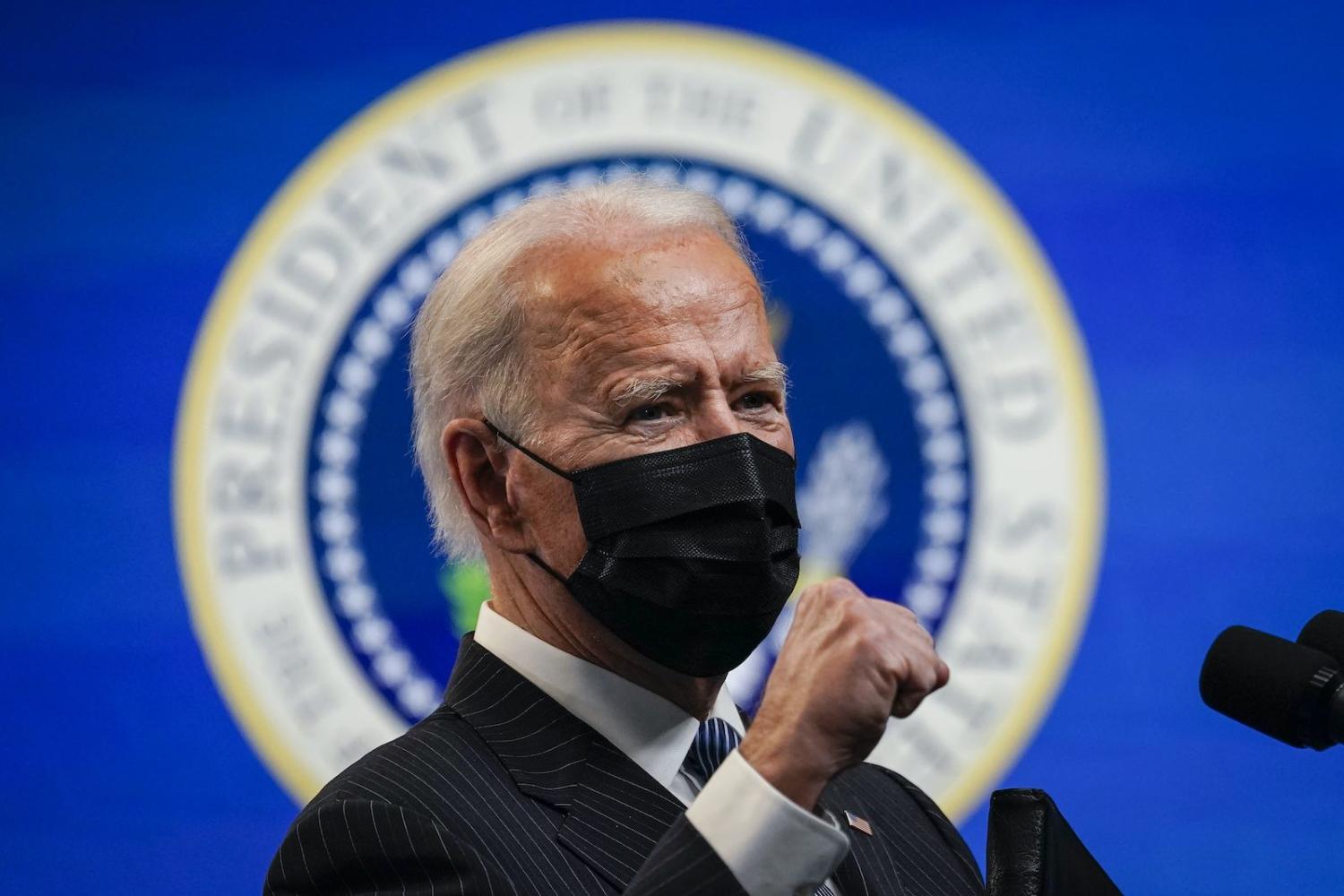

In the first week of Joe Biden’s presidency, Jennifer Rubin, a columnist for The Washington Post compiled a clever list of 50 things that are better already, which included examples of the new administration following the law, conforming to norms and projecting tolerance for all Americans. Rubin’s list captured how a return to normalcy brought many Americans a visceral sense of relief. That sense of relief will need to sustain Americans for a while as the new administration rebuilds the government.

It’s difficult to find anyone these days who feels positive about the Senate’s prospects, but Biden may see things others cannot.

On the most significant challenge facing Americans – the coronavirus pandemic and economic fallout – Trump was mostly absent last year. President Biden has now assumed responsibility for the pandemic and released a federal response plan. Members of Biden’s economic team are engaging with a bipartisan group of legislators to talk through the details of Biden’s $1.9 pandemic relief package. The public health and economic crisis remain dire, but the work has begun.

Republicans have been critical of Biden’s liberal use of executive orders to reverse Trump-era policies and enact a progressive agenda. In many cases, however, such action was necessary to realign Washington with democratic values. For example, the end of the so-called Muslim travel ban, the stop on construction of the southern border wall and the repeal of an aggressive deportation approach all signal a more inclusive and empathetic government. Notably, the Biden team also submitted a comprehensive immigration bill to Congress for consideration.

Legislative progress depends on the capacity of the administration to work with a Senate split 50-50 (with Vice President Kamala Harris providing the tie-breaking vote). To this challenge, Biden brings 36 years of experience in the Senate and a belief that the institution can move beyond the paralysis that has defined the last decade. It’s difficult to find anyone these days who feels positive about the Senate’s prospects, but Biden may see things others cannot.

In late 2020 – post-election but prior to the Senate runoffs in Georgia – Republican Senators were slow to acknowledge Biden’s victory, and slow to schedule hearings for his Cabinet nominees. In December, Biden’s aides reportedly grew concerned and discussed an aggressive public campaign to support the nominees. Biden counseled patience, explaining that the Senate needs some space and can get to yes on its own.

It appears he was right. The initial rounds of confirmation hearings for Biden’s nominees were relatively quiet and courteous. When Secretary of State nominee Tony Blinken sat in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (SFRC), Republican members struggled to identify many areas of disagreement. Blinken, who served as the Democratic Staff Director for the SFRC prior to his time in the Obama administration, is well prepared to establish a productive working relationship with the Committee, which he will need in order to rescue a deeply demoralised State Department.

Further, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell backed down on his demand that the new Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) commit to leaving the filibuster in place for legislation prior to agreeing on the organisation of the new Senate. The filibuster requirement for a supermajority generally applies to legislation, but not to confirmation of judges and Supreme Court nominees.

Biden currently opposes getting rid of the filibuster, but there are different ways to work around it. Policy that could be passed through the budget reconciliation process only requires 51 votes. And some filibuster reform advocates have suggested getting rid of the filibuster in one specific area that would produce immediate democratic benefits: voting rights.

Finally, Biden’s longtime Senate career means that he brings a unique perspective on the presidency – namely that he does not believe in the imperial presidency. In recent decades, Congress has ceded powers to the president related to trade authorities and national security, powers that allowed Trump to institute the travel ban and apply tariffs to America’s allies, for example. Legislation returning these powers to Congress would protect the country from the next Trump.