Vulnerable cases

Early efforts to contain Covid-19 focused on quarantining those travelling by air, leaving the impression of coronavirus as a disease mostly affecting stable and industrialised nations with busy transport networks. Of course, the danger was always more widespread, particularly in fragile countries already under pressure from long-standing conflicts.

So in worrying developments from Iraq, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reports 83 new cases of the virus in the country since 10 March, the first of which were recorded in a camp for internally displaced persons.

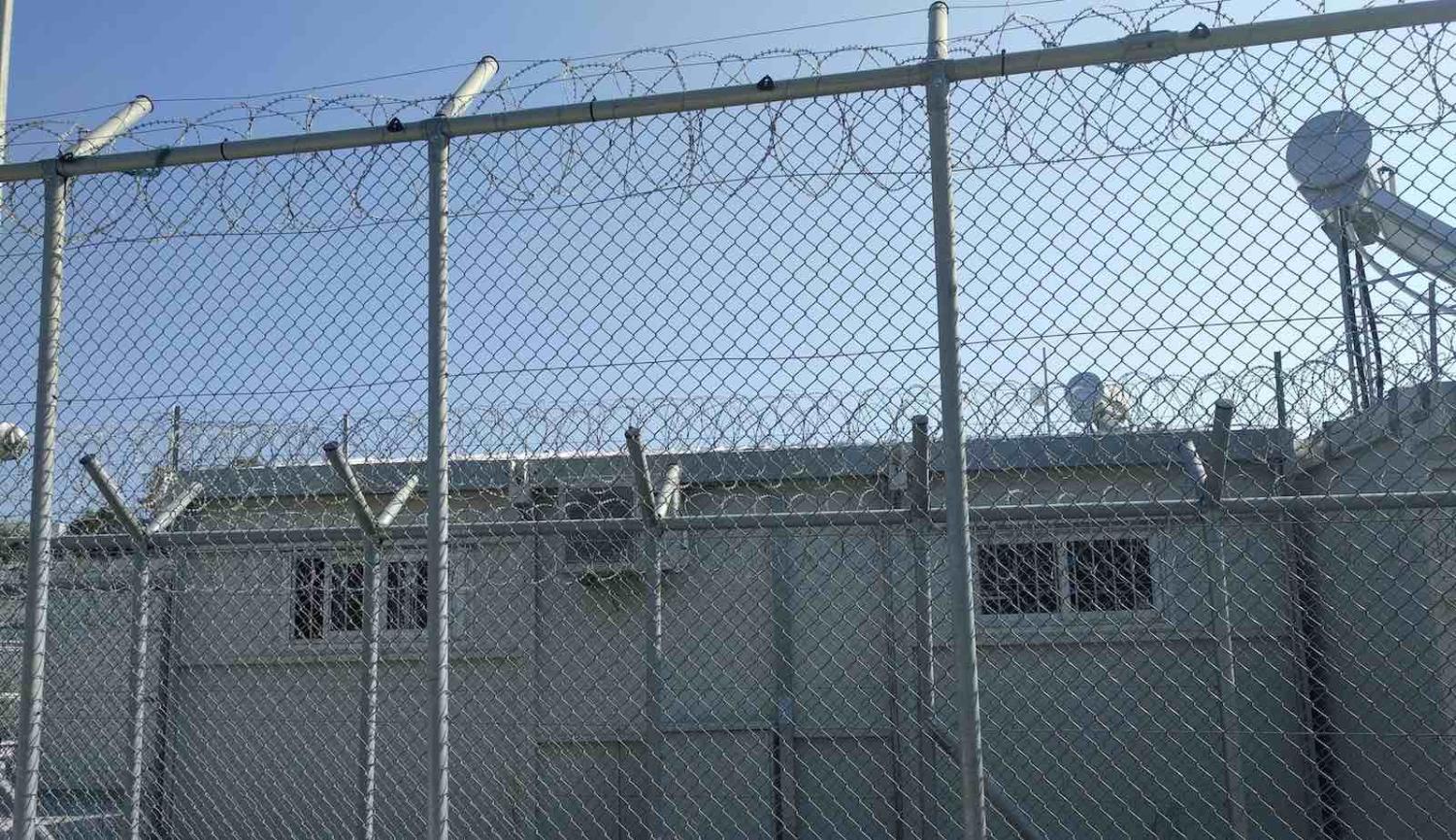

But outbreaks are also evident elsewhere where people have fled. A confirmed case of Covid-19 on the Greek island of Lesbos has also sparked fears of an outbreak at the Moria refugee camp, where over 20,000 refugees live in squalid conditions without proper access to medical care. Violence on the island has already led to humanitarian organisations suspending operations there.

As if refugees didn’t have enough to worry about, the pandemic now seems inevitable among refugee populations.

Refugee standoff

A Turkish court has sentenced three people smugglers to 125 years each for their involvement in the drowning death of Syrian Kurdish toddler Alan Kurdi, his brother, and the children’s mother in 2015. The image of Alan’s tiny lifeless body of lying face down on a Turkish beach provoked global outrage and sympathy at the plight of refugees in the grip of a mass migration wave in 2015.

The image resonated particularly strongly in Germany, which went on to take in more than a million Syrian refugees – a move that has had profound political consequences for Germany’s domestic politics – and indeed Europe more broadly. It also precipitated a deal between the European Union and Turkey in which Turkey agreed to step up border patrols and take in millions of Syrian migrants returned from Europe in exchange for roughly $12 billion in aid.

But after a blistering air campaign by Syrian government forces and their Russian backers against civilians in the Syrian province of Idlib prompted a new wave of displacement, Turkey reneged on the deal, announcing it would once again fling open its gates to Europe and assist Syrian migrants in attempts to flee to the continent.

A tense standoff between Turkish and Greek border guards ensued; with 35,000 Syrian migrants massed at the border, Greek border guards fired tear gas to repel the crowd, including women and children. Footage also showed Turkish security officials standing by while migrants tore down parts of the Greek border fence.

Now, the same week as the sentencing, Turkey has announced it will suspend its operation to aid the migrants to Europe.

So the crisis appears averted for now. Taken together, these events can be interpreted as an indication Turkey is once again willing to play a part in stemming a new wave of migration to Europe.

It is also a reminder – as no doubt Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan intended – that Turkey holds significant leverage in controlling the flow of migrants to Europe, which remains beholden to Turkish whims, and that Turkey is willing to use the plight of refugees to secure its objectives as required.

Water wars

Sudan is leaning towards Ethiopia in an escalating disagreement with Egypt over a Nile dam project – a dispute many fear could lead to war.

Ethiopia initiated the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project to provide much-needed electricity for its 100 million people. Upon completion, it will be Africa’s biggest hydroelectric plant.

With the dam more than 70% complete, an agreement is becoming increasingly urgent, but further out of reach.

Egypt says the dam project was initiated without consultation and fears filling the dam’s reservoir too quickly could lower the Nile’s flow and impact Egypt’s water supply. Egypt relies on the Nile for 90% of its water supply to its 100 million population.

The US has sponsored talks between Ethiopia and Egypt in the ongoing dispute and has said the dam should not be completed without an agreement in place. Ethiopia failed to attend the last round of talks in Washington and has accused the US of overstepping its role as a neutral observer. US Donald Trump enjoys cordial relations with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El Sisi.

Sudan has now refused to get on board with an Arab League resolution which expressed support for Cairo’s position that the dam should not infringe on its historic rights to the River Nile waters. Sudan is hoping the dam will also provide it a cheap source of power.

With the dam more than 70% complete, an agreement is becoming increasingly urgent, but further out of reach.

MBS purge

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s ruthless quest for power has seen him purge more senior officials. On Sunday, 298 officials, including military and security officers, were arrested on charges involving bribery and exploiting public office. It follows the arrest last week of two of MBS’s senior family members – his uncle and brother to the King, Prince Ahmed bin Abdulaziz, and the cousin he deposed as crown prince in 2017, Mohammed bin Nayef.

As the well-connected Michael Stephens of the Royal United Services Institute RUSI has pointed out, only MBS can know the reason behind this latest purge, and, in reality, the two senior royals posed little threat, having already been silenced or put under house arrest.

What is worth noting is that MBS seems entirely uninhibited by the international reputational damage his actions cause – including the order for the dismembering murder of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate Istanbul in 2018, and Saudi Arabia’s disastrous war in Yemen.

This latest purge has prompted renewed speculation that the health of his father, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, may have deteriorated significantly – the implication being that the ageing monarch was unaware of his son’s power grab. But on Sunday, the Saudi royal court circulated photographs of the 84-year-old monarch performing royal duties.

Alternatively, the move has led to reasonable speculation that an attempt at a coup was under way, and that the king has given his son approval to carry on quashing dissent unopposed in any way he sees fit.

Still on Saudi Arabia and The New York Times’s talented Beirut-based Middle East bureau chief Ben Hubbard has just released a new book profiling the young prince, MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed Bin Salman. Hubbard has spent more than ten years covering the Middle East, and some of his most fascinating work was filed from Saudi Arabia.