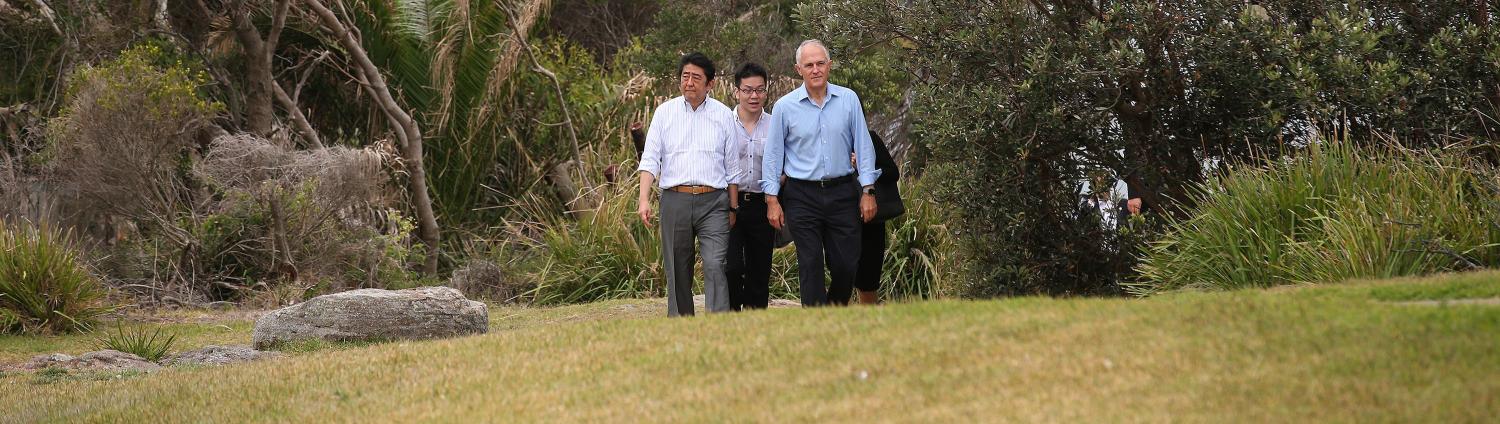

Although it took place at Kirribilli House, just around the corner from where I live, I can unfortunately claim no inside information on last weekend’s Sydney summit between Prime Ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Shinzo Abe. From this nosy neighbour’s reading though, the outcomes on defence and security cooperation fell substantially short of the relationship’s potential.

The main defence 'deliverable' announced was an upgrade to the existing Japan-Australia acquisition and cross-servicing agreement (ACSA). In addition, both sides pledged to deepen training and joint operations through a 'reciprocal access agreement' between Japan’s Self Defence Forces (SDF) and the Australian Defence Force (ADF), to be concluded later this year.

Although Abe and Turnbull met at the ASEAN summit in Vientiane last September, this was the Japanese Prime Minister’s first visit to Australia since 2014, and the first summit between the two leaders since the Turnbull Cabinet’s decision to award Australia’s future submarine contract to France. In that context, it is surprising there was not more ambition to deepening bilateral defence cooperation.

Defence professionals would understand that an upgraded ACSA constitutes a low bar for cooperation between the two US allies with probably the greatest potential for strategic partnership in the Western Pacific. The main augmentation to the 2013 ACSA will allow the SDF to supply ammunition to ADF where they operate alongside in UN peacekeeping operations and joint exercises. While welcome, this looks like a largely symbolic commitment, although the two militaries do operate similar (though not identical) weapons systems.

It is well known that Abe felt the disappointment of the submarine decision personally. In the awkward aftermath, Japanese defence officials uncharacteristically let it be known that they felt misled by the Australian Government. While it is also the case that some defence officials and industrialists in Japan were privately relieved that the Japanese bid fell through, many still expected at least a face-saving commitment by Australia to collaborate with Japan’s defence industry at some level. Mitsubishi, after all, opened a new representative office in Australia partly in anticipation of winning defence business not only relating to submarines.

Shared concern about China’s creeping takeover of the South China Sea, or the risk that the incoming Trump administration might dilute US defence treaty commitments ought, logically, to be spurring Canberra and Tokyo into greater activity. Yet beyond the above agreements and passing reference to North Korea and the South China Sea, there wasn’t much concrete evidence to support this from Saturday’s press conference. A joint statement reportedly goes somewhat further, expressing ‘serious concern’ about the South China Sea.

It is of course possible that areas of defence cooperation deemed too sensitive for public release were discussed between Mr Abe and Mr Turnbull. However, I suspect that the weekend summit failed to deliver any significant advance in defence and security cooperation for the more basic reason that Australia and Japan are currently more united in mutual caution than shared strategic ambition for the bilateral defence relationship. What might account for this?

On Japan’s side, since Tokyo’s acute threat perceptions towards China have hardly moderated, Abe could have elected to moderate his ambitions for a strategic partnership with Australia, judging the Turnbull administration either too fickle or risk-averse on China to justify investment of more political capital beyond 'natural' incrementalism in defence ties, as represented by the upgraded ACSA. In the run-up to Sydney, Abe’s visits to the Philippines (including a tour of President Duterte’s bedroom) and Indonesia were arguably more ambitious.

On the Australian side, the onus being on Turnbull as Abe’s host to take the lead on new policy initiatives, it arguably speaks to a prevailing caution on Canberra’s part to maintain some strategic distance from Japan, for fear of entrapment in Tokyo’s troubled relationship with Beijing, or upsetting the economic apple-cart of trade and investment from China. If Canberra is primarily worried about an apparent US tilt towards a more confrontational approach towards China under Trump, then alliance considerations could, in fact, act as a brake on bilateral defence cooperation with Japan. A more assertive Washington can be expected to press its security treaty partners in Asia to adopt new roles and missions potentially beyond their comfort levels, seeking opportunities to ‘trilateralise’ inter-alliance cooperation. The Trump factor may have reinforced Turnbull’s natural caution about being ensnared in the Thucydides trap.

I may be wrong. But if I’m right, and last weekend’s summit constitutes something of a plateau in Australia and Japan’s strategic cooperation, this does not bode well as a signal for the wider region. As this recent article by the Thai scholar Thitinan Pongsudhirak persuasively argues, there are sound strategic reasons for Southeast Asia to pursue defence cooperation with both Japan and Australia. If Japan and Australia are either unwilling or unable to get their bilateral defence act together beyond a cosmetic ACSA upgrade and reciprocal access agreement, then more equivocal players in the region are unlikely to set their own bar much higher.