I have a modest proposal to make for Australia to directly engage with North Korea.

Australia maintains diplomatic relations with North Korea, but has no representation in Pyongyang. Instead, Australia's embassy in Seoul is cross-accredited, a common arrangement among countries that lack an official presence on the ground. Likewise, there is no North Korean embassy in Canberra. The job of handling relations with Australia falls to Pyongyang's mission in Jakarta.

Australia's official relationship with North Korea has been a stop-start affair. The two countries opened embassies under the Whitlam government in 1975. But the experiment did not last long and within a few months Australia's diplomats were unceremoniously told to pack their bags.

Relations improved following then-Foreign Minister Alexander Downer's visit to Pyongyang in 2000, as part of a wider Western thaw. A North Korean embassy was re-established in Canberra, but shuttered in 2008. North Korea requested permission to re-open a mission in 2013, but this was turned down. The Obama administration is understood to have approached Canberra about re-establishing an Australian presence in Pyongyang, but Canberra has been cautious about committing scarce start-up resources to such a see-saw relationship.

Australian diplomats, including Australia's ambassador in Seoul, have normally visited the North yearly. However, these visits have recently stalled and Australia's current representative in Seoul, James Choi, has yet to present credentials in Pyongyang. North Korean officials do travel to Canberra, but infrequently.

In the current climate of tensions over Pyongyang's nuclear and long-range missile tests, Australia's diplomatic relationship with the North is likely to remain at a low ebb. There is no appetite in Canberra for upgrading ties, especially when Washington is leading a campaign to diplomatically isolate the North, prompting several countries (in Latin America, Europe and Africa) to declare the resident North Korean ambassador persona non grata and to otherwise downgrade relations with Pyongyang.

Still, Australia can use its lean diplomatic profile with North Korea to advantage. Even the conservative columnist Greg Sheridan recently argued the potential benefit of some engagement with the regime, including the potential re-opening of an Australian Pyongyang embassy in the future.

There is an alliance value to consider. Washington is highly receptive to receiving counsel on North Korea from close allies such as Australia, especially given the severed links between the Trump administration and the Republicans' traditional caucus of US-based expertise on Asia and Korea. The value of Australian advice and intelligence on North Korea has never been higher.

It is also clearly in Australia's direct interests to be shaping the contours of US North Korea policy as constructively as possible, and to be heard by Pyongyang and the other key players on the Peninsula. More broadly, Australia should not be afraid to articulate what kind of US North Korea policy it wants to see.

Washington has other close allies, notably the UK, that maintain embassies in Pyongyang. I was a regular visitor to the UK embassy between 2004 and 2009. One of those trips coincided with the visit of Lord Guthrie, former Chief of the UK Defence Staff. Occasional contacts such as these were not exactly backchannels, but they nonetheless opened doors to the Korean People's Army (KPA) that might otherwise have remained shut. There is no reason Australia could not do something similar.

Maintaining backchannels or simply informal contacts with the North Korean military, in both sending and receiving mode, is of heightened importance at times of crisis.

So here is my modest proposal. Australia's embassy in Seoul should invite a former Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) to join a Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade delegation visit to Pyongyang. Washington would be consulted in advance, and there is good reason to think that key figures in the Trump line-up, including Secretaries Rex Tillerson and Jim Mattis, would be receptive to this. A former CDF would have sufficient 'entrée' to meet with senior KPA officers, without handing Pyongyang the kind of propaganda opportunity that both Canberra and Washington wish to avoid. As a vocally non-nuclear power, as well as a close ally of the US, Australia would be well-suited to this role. While the US has its own channels to North Korea (three according to Tillerson), military-to-military dialogue is an obvious blind spot – all the more so following Trump's 'save your energy Rex' Twitter admonishment to his Secretary of State.

A former Australian CDF would not be there to negotiate. But he (they all are) would have the authority to convey messages from Washington discreetly, without the same political baggage. And he would be there not only as a messenger, but to impress an Australian viewpoint to the North Koreans – if only to remind them that Canberra has its own concerns and interests in play, including being on the receiving end of recent North Korean threats.

This kind of engagement should not be confused with rewarding bad behaviour. It may, in fact, dovetail with the US administration's emerging good cop/bad cop routine on North Korea. Any mistaken notion that Australia was breaking ranks by visiting Pyongyang could be quickly dispelled.

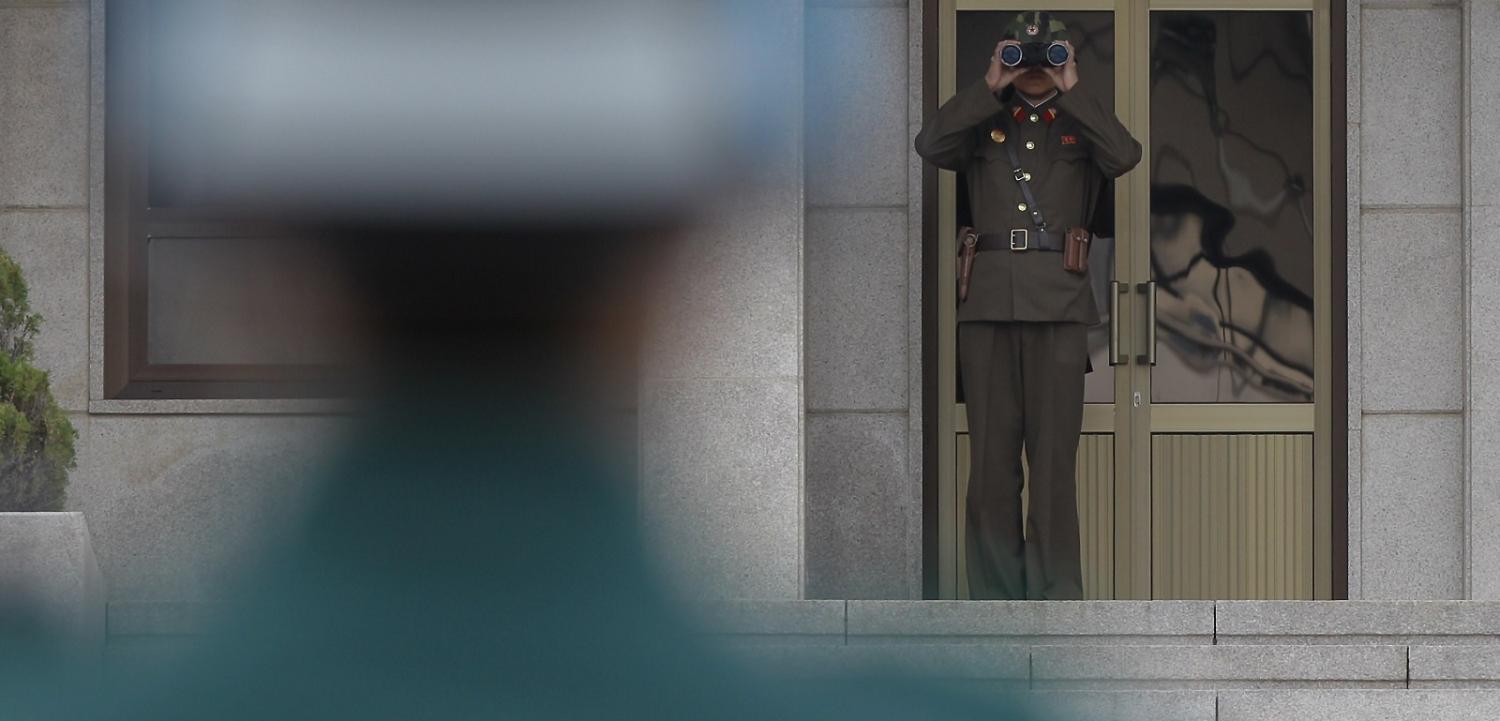

It is possible that the KPA leadership might just recognise anew the dangers of self-imposed isolation, now that its break-neck progress towards a nuclear Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) has raised the stakes of accidental conflict to such high levels. Hotlines across the Demilitarized Zone that are designed to prevent this scenario have gone unanswered by the KPA for several years. A visit from Australia's former top person in uniform could present the KPA with an overdue and potentially face-saving opportunity to re-establish crisis communication links – but also to begin a necessary dialogue on nuclear crisis management.

The North Koreans may very well say no. But there's little harm in trying. Even if North Korea test launches an ICBM tomorrow, the logic will still apply.