As the year winds down, it's time to look back on the biggest stories in the always-tense northeast Asian region. End-of-year lists are a useful, if soft, methodological tool in that they force a ranking or prioritisation on events. Issues that may seem like a big deal at the time can blow over, while others reveal themselves as more critical. In that vein, here are the five biggest regional shifts for the year 2016:

1. The election of Donald Trump

Asian security has turned, since World War II, on the American regional commitment. During the Cold War, the US and Japan held communism at bay. When China partially defected from ‘socialist fraternity’ in the 1970s, it informally lined-up with the American ‘hegemony’. Today, it would like the US to leave the region. As the region’s balance of power shifted after the Cold War, the US again played a dampening role, this time on China’s regional ambitions. Smaller states in the region have generally supported America’s post-Vietnam footprint here for that reasons.

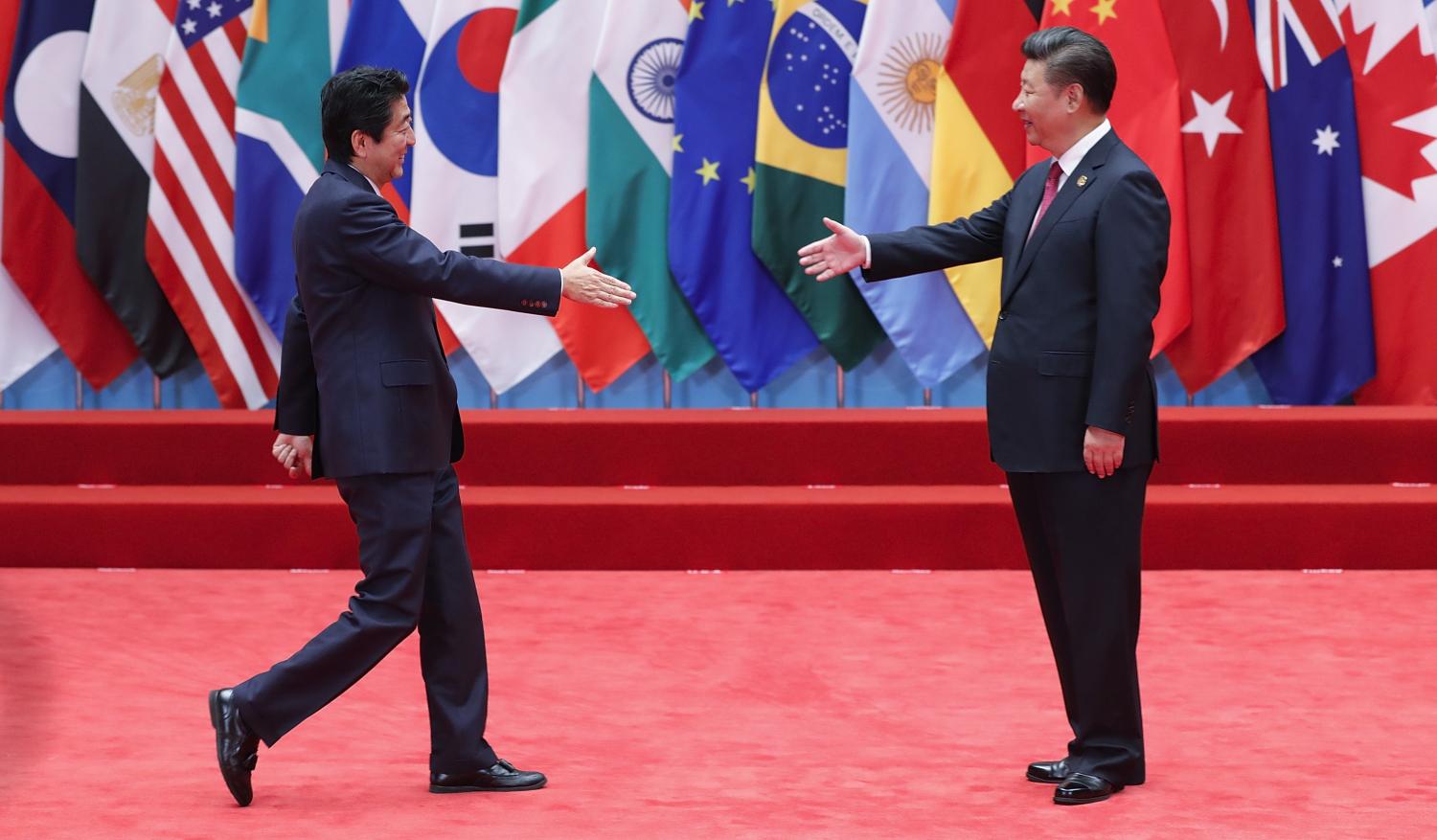

All of which makes the erratic, theatrical Donald Trump a hugely destabilising prospect. This is a business-like region, where elites tend toward dark suits, grey hair, and bland seriousness. Trump, right down to his orange skin and penchant for flamboyant lying, is the antithesis of this demeanour.

And indeed, the buffoonery and destabilisation have already started. Trump brought family business members, but not a US-side translator, to his first meeting with Shinzo Abe. He has already managed to provoke China in ways far more serious than he probably realises with the Taiwan phone call. By contrast, had Hillary Clinton been elected, that event would not have made this top five.

2. The impeachment of the South Korean President

Park Geun Hye was impeached by the South Korean parliament on 9 December. The vote was badly lopsided against her (234-56), and her approval ratings are at an astonishing 4%. South Korea’s Constitutional Court must now take up the case within the next 180 days. I believe they will impeach her, forcing a new presidential election within sixty days, which the left will almost certainly win (my thoughts on ‘Choi-gate’ are here, here, and here).

The left’s victory will likely re-orient South Korean foreign policy. The left here continues to believe in the Sunshine policy, a policy of engagement and dialogue (or appeasement, to conservatives) with North Korea. It continues to oppose intelligence sharing with Japan (even though South Korea benefits much more than Japan from that). And it continues to oppose the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense missile defence system (THAAD, see more at number five on this list). The latter two were pushed through by Park just prior to the explosion of ‘Choi-gate.’ If the left wins the presidential election by a wide enough margin, it may re-open those decisions.

Finally, the leading candidate on the left, Moon Jae In, has now begun speaking of South Korea taking a ‘balancing’ position between China and North Korea, and the US and Japan. This will almost certainly re-open US alliance issues, as an American defence commitment to South Korea is politically unsustainable, especially in the Trump era, if South Korea’s rejects its position as an ally.

3. The two North Korean nuclear tests

It is practically a requirement that any list such as this include North Korean shenanigans and hijinks. This year’s outrage was two nuclear tests in just nine months. The first, on 6 January, was approximately 10 kilotons; the second, on 9 September, was approximately 30 kilotons. The yield of that last test means Pyongyang now has a weapon more powerful than those the Americans used against Japan.

Two tests in nine months breaks North Korea’s pattern of roughly one test every three years. It is unclear what signal the second test was intended to send. Perhaps it was simple defiance. The fourth nuclear test provoked a tough new sanctions package, so perhaps the fifth test is to inform us that no matter how much we sanction them, they’ll just keep charging ahead.

The last test also finally revealed the open secret that no one seriously expects North Korea to denuclearise, when the American director of national intelligence admitted as much. Denuclearisation is formal US policy, but I cannot think of anyone in the North Korea analyst community, hawk or dove, who thinks it will happen. North Korea is now a nuclear-weapons state whether we like it or not.

4. South China Sea cat-and-mouse ramps up

This is not exactly in northeast Asia, but it involves China and likely will suck in Japan in the future. China’s expansion into the South China Sea has been twenty years in the works, but this year, the zero-sum nature of the tussle over control starkly emerged with Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s defection from the shaky coalition to push back against Chinese control.

Ironically, it was the Philippines that brought the issue to the Hague, where it won a major ruling in its favour in July. But in October, newly-elected Duterte jetted off to Beijing to apparently make a deal exchanging acceptance of Chinese claims for development assistance. He made sure to add while there, 'I announce my separation from the United States…Both in military, not maybe social, but economics also. America has lost'.

It is unclear if Duterte can bring the very pro-American Philippine military with him. Nor is it clear if Duterte can survive the public backlash if he surrenders the islet closest to the Philippines, Scarborough Shoal, to overt Chinese control. But like many states around China, he is far more eager to trade with China than fight with it. Hawks expecting a robust anti-Chinese coalition have not properly grappled with how well Beijing has forestalled that eventuality with offers of trade and assistance – which makes Trump’s decision to cancel the Trans-Pacific Partnership all the more misguided.

5. THAAD

This was also the year South Korea finally agreed to missile defence. The system is not nearly as destabilising as China says it is, but China has chosen to plant its flag on this issue, so it makes the top five. THAAD provides only enough shielding to partially deter North Korea and defend mostly US assets in South Korea. It does not provide robust coverage of South Korean cities, nor do THAAD radars peer into China (as the Chinese so duplicitously and endlessly argue). America has satellite assets that cover Chinese launches of strategic missiles.

Nevertheless, China has framed this as a fork-in-the-road issue for South Korea. An overt choice between the US and China has long been an existential anxiety for Seoul, and it is curious why Beijing chose this issue to force that choice. So uncomfortable was the South Korean left with Park’s acceptance of THAAD that several opposition lawmakers flew to China the day after the decision to apologise. Moon’s ‘balancing’ comments capture this strategic tug-of-war as well. China is now forcing on Seoul a long unwanted grand-strategy debate.