The unassuming storefront sits in an old-school complex next to Singapore’s National Library, and is easily overlooked in the building full of bookstores and stationery shops.

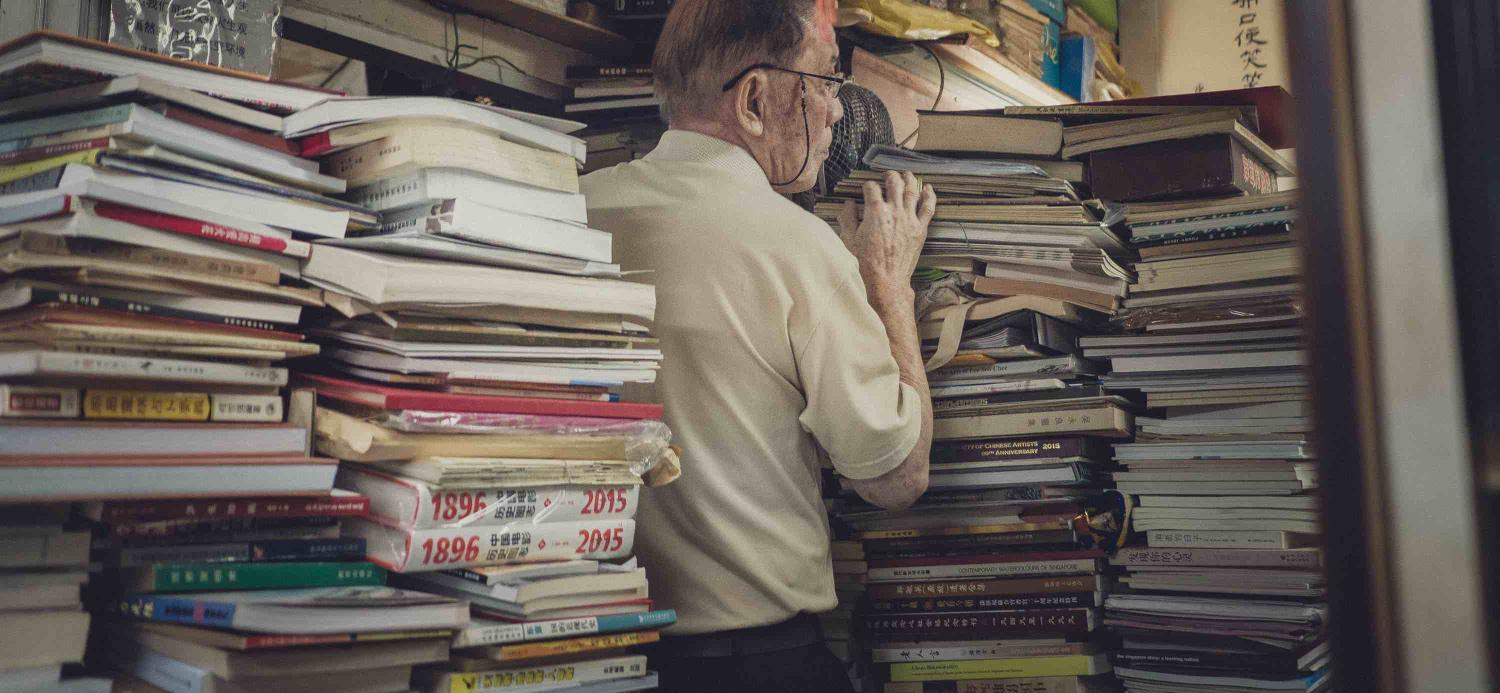

Inside, Xinhua Cultural Enterprises is part bookstore, part archive, and moving between its narrow aisles is a squeeze. Books, pamphlets, and magazines are crammed into shelves and piled in high stacks. Only its elderly proprietor, Yeo San Chai, knows where everything is.

Yeo spoke softly in Mandarin. He said business hadn’t been good for some time, but he had no intention of calling it quits. The store is more than just an enterprise to him. Having little formal education, Yeo credits the 64 years he has spent working in bookstores for who he is today.

But Yeo had another source of education: the 15 months he spent in detention, without trial, after his arrest in 1963.

“In those 15 months [it was as if] I was at the ‘School of Life’,” Yeo said. “It changed my outlook on life and the world. I see things more clearly and holistically [after my detention].”

On 2 February 1963, more than 100 unionists, anti-colonial activists, and politicians were detained without trial in a series of arrests code-named Operation Coldstore. The authorities justified the action as necessary to “safeguard against any attempt by the Communists to mount violence or disorder in the closing stages of the establishment of the Federation of Malaysia”.

Special Branch case files listed security classifications for each detainee, ranging from “communist” and “communist sympathiser” to the more vague “suspected communist sympathiser” and “fellow traveller”. None of these labels were proven in a court of law.

Although this operation holds the dubious honour of involving the largest number of arrests ever made in Singapore, knowledge of Coldstore among Singaporeans today is dismally low. A survey carried out in 2015 found that only 16.6% of 1500 respondents were aware of the event.

It seemed as if the history of the operation would continue to languish in obscurity, glossed over in school textbooks, until suddenly Coldstore was in the public eye, propelled into the spotlight by an unexpected source.

When my colleague Dr Thum Pingtjin appeared in March before the Singaporean Parliament’s Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods, he had expected to be asked questions about “fake news” and what Singapore should do about it. That was, after all, the committee’s stated purpose.

What he experienced, instead, was a six-hour cross-examination of his work as an historian of Operation Coldstore and communism in 1960s Singapore, after which his credentials as a University of Oxford academic were questioned.

Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam, a former litigator, seized upon a point made in Thum’s written submissions to the committee: that Operation Coldstore had been an example of the government, under the ruling People’s Action Party and its then-leader Lee Kuan Yew, spreading falsehoods. Thum argued that the operation had been:

conducted for political purposes, and there was no evidence that the detainees of Operation Coldstore were involved in any conspiracy to subvert the government.

It wasn’t the first time he’d made this assertion, but the government wasn’t going to let it go this time.

“These are serious allegations made in Parliament about our founding [prime minister Lee Kuan Yew],” wrote Shanmugam in a Facebook post defending the way he’d questioned Thum. “Either they have to be accepted, or shown to be untrue. Keeping quiet about them was not an option.”

The marathon session sparked a sudden interest in Coldstore and the interrogation of Singapore’s history. Journalists, academics, and politicians alike took to the mainstream media to argue their positions.

While this went on, Yeo continued running his bookstore in the city centre. Singaporeans following the news, or arguing on Facebook about the motivations of “leftists”, could have walked straight past his shop, oblivious of their proximity to someone with first-hand experience of the event in question.

In Singapore, history is often discussed as a series of fixed facts. Places and dates are memorised, and the “Singapore Story” is internalised and regurgitated when necessary. If someone is definitely right, another person has to be maliciously wrong.

This is a pervasive mindset, as exemplified by a statement from a member of the Select Committee who said, during my appearance at an open hearing two days before Thum’s session, that “there should really only be one truth”. The concept of history being a matter of interpretation, argumentation, and contestation is only now slowly taking root.

Yet Singapore is in a very particular position: the relatively young country looks like a major metropolis, but remains a small island at heart. Former detainees of Operation Coldstore have gone on to work as translators, doctors, lawyers, and, like Yeo, booksellers. They’ve had children and grandchildren. Singaporeans might be shocked to find themselves more closely connected to a former Coldstore detainee than they might believe. A son and nephew of Coldstore detainees even sat on the Select Committee itself.

Although the government insists that Thum’s work is “not scholarship, but sophistry”, it also refuses to declassify documents related to the period. A former Special Branch officer argued that, although 55 years have passed, declassification would be a “betrayal” of past informants.

The government has once again pledged to launch a series of discussions about the country’s future, open to all Singaporeans to participate in. Coming to terms with the past – even if this might expose the ruling party and its much-revered former leader to scrutiny and criticism – is surely an important part of a national dialogue on where to go next.

There is no better time for a national reckoning and reconciliation. While the decades have tempered the rawness of Operation Coldstore, the events are still recent enough for former detainees, such as Yeo, to add their testimonies – so sorely lacking in the mainstream discourse, even throughout this recent hullabaloo – to the conversation.

Kirsten Han is a freelance journalist and editor-in-chief of New Naratif, a platform for Southeast Asian journalism, research, art, and community-building that she founded with Dr Thum Pingtjin, among others. She had also appeared before the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods.