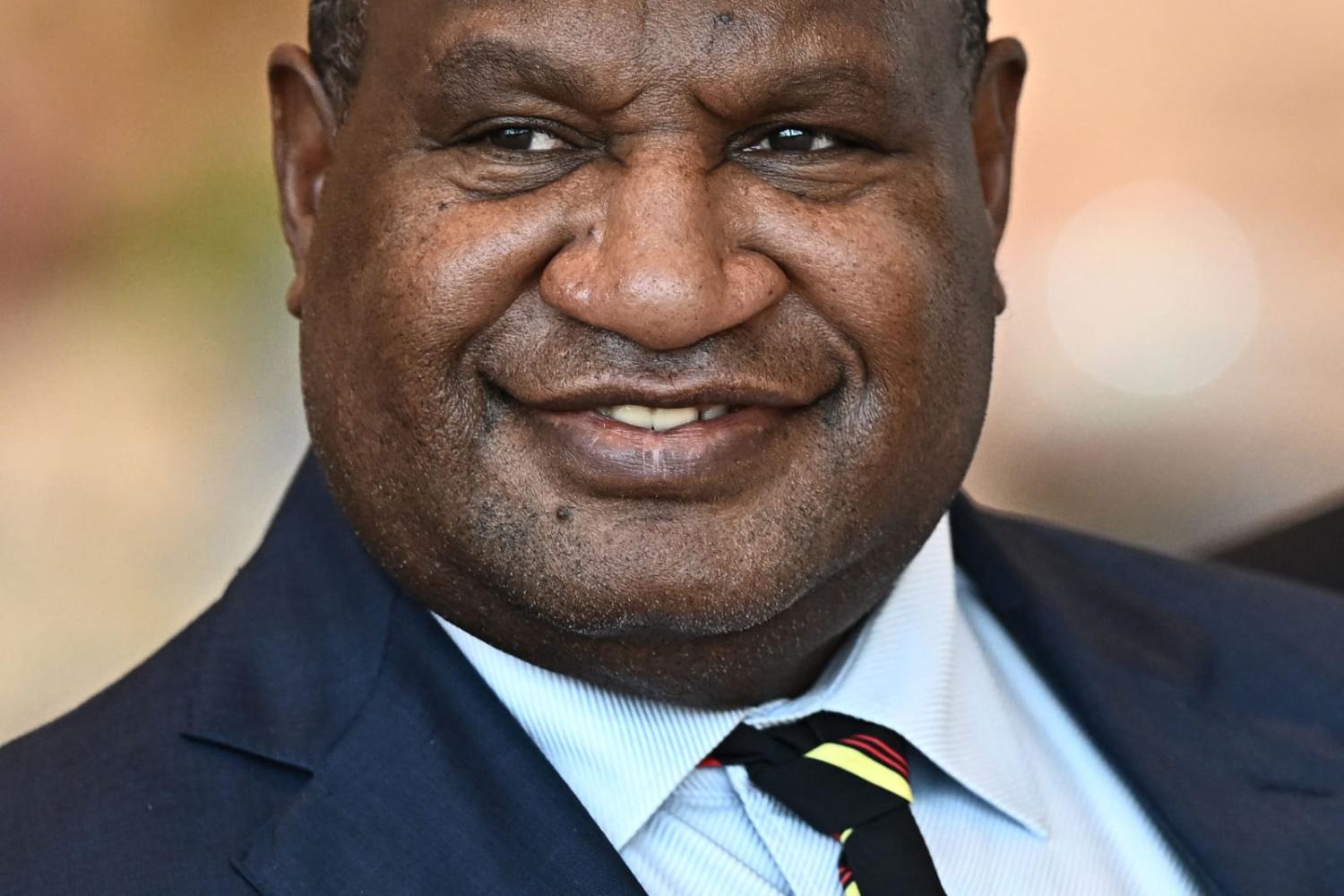

In January, Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister James Marape announced that the constituency development funds allocated to MPs will be increased this year to K3 billion (A$1.2 billion), up from the current K1.8 billion. This increase – assuming it is actually delivered, depending on government revenues – would see K20 million each allocated to the 96 open MPs representing the districts, roughly doubling the current allocation. The formula for the 22 regional MPs representing the provinces is yet to be determined, although previously a province was given K5 million for each of its districts, making Morobe, which had nine districts, the largest beneficiary with K45 million.

The nomenclature here is important to grasp the scale. Constituency development funds for the open MPs are known as the District Services Improvement Program (DSIP) funds, and the allocation to regional MPs is called Provincial Services Improvement Program (PSIP) funds. In addition to the DSIP and PSIP funds, the government allocates District and Provincial Infrastructure Program funds respectively to the districts and provinces. For 2023, a combined total of up to K2.4 billion will be distributed to PNG MPs.

Taken together, these funds as a share of capital expenditure rank as one of the highest in the world, alongside Solomon Islands. But such an approach raises questions about probity, governance and the distraction from MPs legislative duties.

One of the more troubling concerns is the speculation on social media (and on the streets) that increased violence during elections is tied to constituency development funds. While such claims are unproven, the logic goes that because much of PNG’s population is rural based, with high levels of unemployment, voters (as well as candidates for elections) see access to funds as the easiest (or the only) way they can benefit from state resources. The discretion allowed for MPs to direct the funding enables them to reward their electoral support base and ignore areas where they do not collect votes. Elections then become an opportunity to agitate for access to state resources rather than selecting the best representative. Tribes and clan groups fight, intimidate or bribe to ensure their candidate wins.

The United Nations estimates that about 265,000 people were affected by electoral-related violence during the 2022 campaign in the Highlands region alone. The increasing rates of strife are difficult to explain without a strong motivation, so if constituency development funds are indeed contributing to electoral violence in PNG, these funds have become a source of security concerns.

Governance issues are another worry. Senior officials have complained that 40 per cent of MPs did not adequately account for spending of funds last year – meaning more than K400 million was not acquitted. There are concerns about “ghost projects” or sub-standard proposals and a lack of resources to monitor delivery or quality, and such concerns go back years. Furthermore, these funds distract the MPs from their legislative duties as they prioritise their service delivery role. An example of this neglect is that about 370 of PNG’s laws remain outdated by more than half a century.

In announcing the increase to the constituency development funds, Marape singled out a role for the Independent Commission Against Corruption, which is not in operation, to prosecute any misuse of the monies. However, governments in PNG have failed to follow through on past promises to increase funding for anti-corruption agencies.

Constituency development funds have become embedded in PNG politics. The two instances where a PNG prime minister completed his term in parliament also coincided with high allocations, demonstrating the way the funds are used at a national level to win political support. Marape would be conscious that votes of no confidence will be allowed from the beginning of next year. MPs also see the funds as a vehicle for electoral success, while voters may see the discretionary fund as a reward for loyalty (although analysis has found the fund did not help MPs with re-election).

To break this spiral, the prime minister and MPs must measure the cost of constituency development funds against the responsibility to foster national progress. At the moment, the costs of this allocation tilt the scale in the wrong direction, and this style of funding should be abolished.