On 30 August, India asked Pakistan to modify the Indus Water Treaty (IWT), a long-standing agreement that allocates the waters of the Indus Basin equally between these two often hostile neighbours. It was the fourth such request since January 2023.

The IWT is regarded as one of the world’s most successful transboundary river-sharing agreements. It includes a strong dispute-resolution framework that has endured multiple wars and crises. But both sides have expressed frustration with the treaty in the past few years. India’s recent requests are the most significant challenge to the IWT since its inception in 1960.

India presented Pakistan with three key reasons to modify the treaty: demographic changes, the need for clean hydropower, and security concerns over the disputed Kashmir region. The catalysts for their requests were Pakistan’s complaints about hydropower projects in Indian-administered Kashmir and the inability of the treaty’s dispute resolution mechanism to deal with these complaints.

As it receives most of its water from this one river system, Pakistan arguably has more to lose if the treaty is renegotiated.

India argues that the treaty favours Pakistan, only allowing India access to about 18 per cent of the basin’s water. Delhi also claims Pakistan has been “exploiting India’s goodwill”, citing ongoing terrorist activities originating from Pakistan. In 2016, after Pakistan-based militants attacked the Kashmiri town of Uri, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed his frustration with the treaty, saying “blood and water cannot flow together”. Pakistan, by contrast, has used the treaty’s dispute system to stall India’s upstream hydropower projects. As it receives most of its water from this one river system, Pakistan arguably has more to lose if the treaty is renegotiated.

There are signs of a thaw in relations, with the Indian government considering sending External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar to Islamabad for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Heads of Government meeting in October. Yet even this move is unlikely to resolve tensions in the historically adversarial relationship.

A potted history

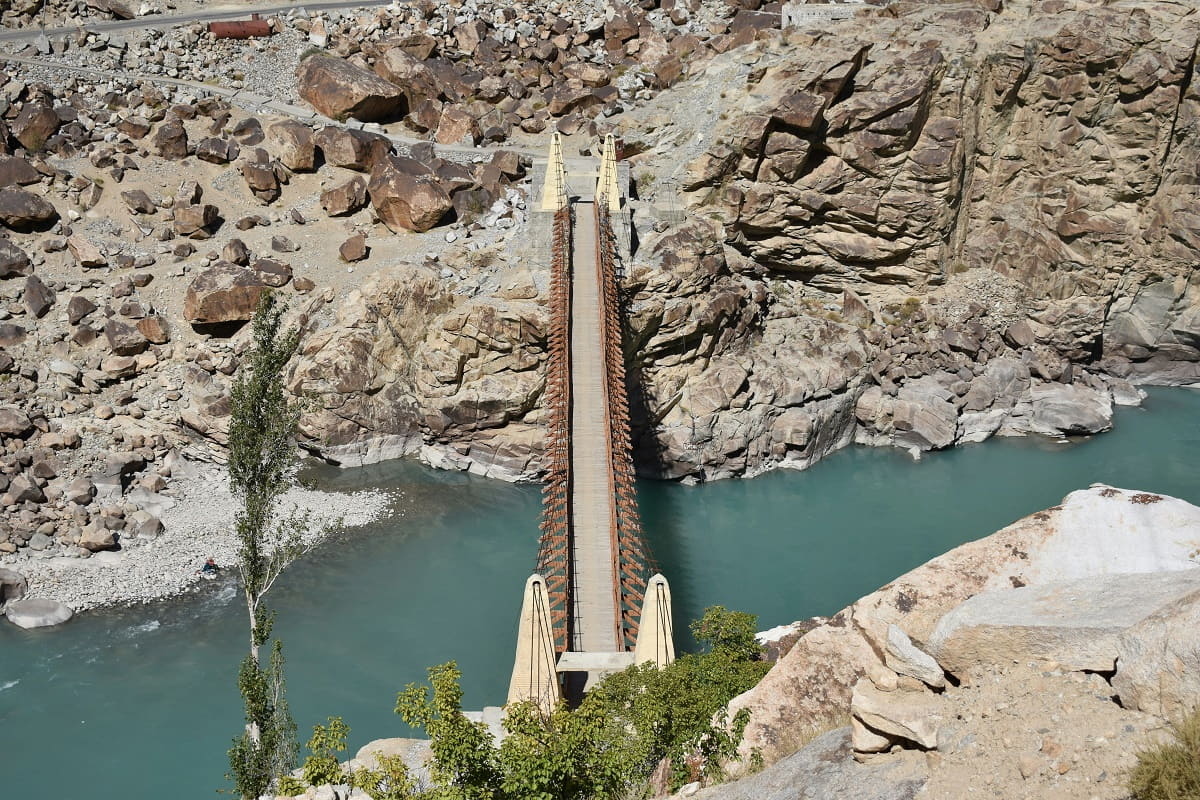

The Indus River catchment is geopolitically complex and hydrologically fragile. Its basin stretches from the Tibetan Plateau in China and northern Afghanistan through India and Pakistan and out to the Arabian Sea. It is home to 268 million people and supports the world’s largest contiguous irrigation network, which depends on glacier melt for up to 80 per cent of its flow. These rivers support 90 per cent of Pakistan’s food production, and across the border, the Indian states of Punjab and Haryana are known as the nation’s “food bowl”.

The IWT is a river-dividing agreement rather than a water-sharing agreement. It grants India sole access to the basin’s three eastern rivers — Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas — and limits its use of the three western rivers — Jhelum, Chenab, and Indus. The cross-border flows of the western rivers must meet Pakistan’s agricultural, hydropower, and “non-consumptive” needs.

The IWT is also legally strong. It has no end date or exit clause, and any modification requires consent from both parties. Requests for modification are the only formal means of renegotiating a treaty that had worked quite well until recently. However, both countries have now substantially increased irrigation systems on their separate rivers, building large flat dams to divert water through extensive canal systems.

The current treaty does little to address sustainability or account for expanding future water and energy demands due to population growth and accelerated economic development.

In the 2000s, Pakistan disputed the hydropower dams India was building on the upper Chenab and Jhelum rivers in Kashmir. Eventually, the international arbitrators ruled that the hydropower projects could be built as “run-of-the-river” dams and did not infringe the treaty by inhibiting water flows. But Pakistan’s complaints frustrated India’s hydropower ambitions. Unfulfilled in the highlands, India built a new barrage on the Ravi River that could entirely stem its flow into Pakistan.

Old water, new political bottlenecks

While India’s request for a review might jeopardise the current treaty, it may also encourage a re-examination that will bring the agreement into the twenty-first century. Rivers do not adhere to political borders, yet the IWT treats them like they do. At present, the treaty divides the rivers in a “divorce settlement” rather than promoting shared stewardship that reflects the river systems’ natural dynamics and potential future stressors.

Climate change has already intensified disasters in the basin. Floods have destroyed infrastructure, and droughts have increased groundwater extraction, affecting the quantity and quality of the basin’s water. Glacier loss and erratic weather patterns, driven by climate change, have altered river flow dynamics, exacerbating both countries’ water resource challenges. To find truly sustainable solutions, India and Pakistan must develop a new treaty that includes adequate flows to sustain wetlands and other riverine ecosystems.

The current treaty does little to address sustainability or account for expanding future water and energy demands due to population growth and accelerated economic development. Nor does it suggest a way to stop political disputes obstructing practical hydrological solutions. Without a concerted effort to re-examine the IWT and make future-focused amendments, this treaty will not continue its past successes.