Getting the leaders of five Asia-Pacific nations together for the photograph amidst the tumult of a APEC Leaders Summit in Port Moresby last November was a triumph of logistics.

But the last-minute scramble to get an upside down Papua New Guinea flag turned the right way up was maybe a sign of how quickly the PNG Electrification Partnership had come together.

The unspoken theme of the summit in Port Moresby had become how the “traditional” powers in the Pacific could counter the growing presence and prominence of the emerging regional superpower – China.

With President Xi Jinping spending two days on a state visit ahead of the summit, and expectations of more big-ticket project announcements – the “traditional” partners, led by Australia, needed something to demonstrate their continued relevance and relationship.

And the Electrification Partnership would be how they did it.

Australia, along with the US, New Zealand and Japan joined together to pledge they would help PNG meet its target of connecting 70% of the country to electricity by 2030. It checked all the boxes: infrastructure, alliances and meaningful development outcomes. And the benefit of an APEC signing photograph with five beaming leaders.

But four months on from the announcement, there’s uncertainty about what the Partnership means – and whether it can realise the ambitious goal of connecting nearly two thirds of PNG’s population to electricity within the next decade.

Per capita, PNG is one of the world’s least-electrified countries. Just 13% of the country’s eight million citizens have the power on. Most of them are in urban centres.

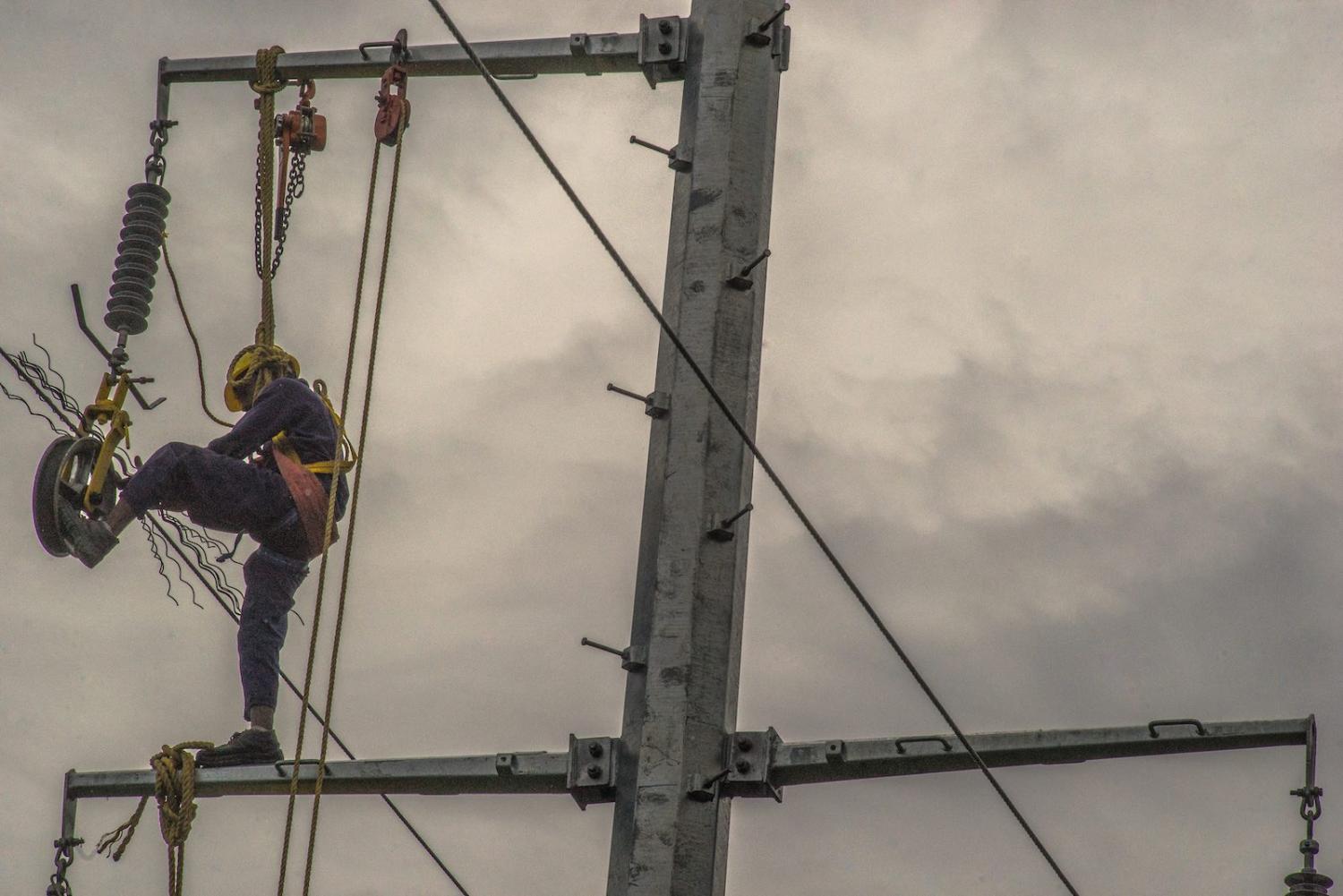

It’s difficult delivering services in one of the world’s most rugged and diverse countries, where four in five people live in traditional rural settings.

Lifting electricity supply has been identified as one of the key goals of the country’s Development Strategic Plan. Launched in 2010, the policy called for 70% of the country’s people to be connected to electricity within 20 years. It projected that achieving the 2030 goal would lift gross national income by 12% and GDP by 10%.

But progress has been extremely limited – with a lack of funding, a complicated government and regulatory regime, and the difficulty of delivering services in one of the world’s most rugged and diverse countries, where four in five people live in traditional rural settings.

That’s before you factor in the complexity of negotiating with landowners for access for infrastructure; and the question of how to get potential electricity customers – who live outside the formal economy – to pay for their electricity – to make the supply sustainable. Access to electricity is estimated to have grown by only 3.4% in total since that 2010 goal was set. An interim target of lifting total access to 33% as part of the 2022 Medium Term Development Plan is well behind schedule.

That’s where Australia and its partners in the PNG Electrification Partnership come in.

Great to be in Wapanamanda with @PM_GOV_PG to launch the Tsak Valley electrification project. It will connect 30,000 to the grid. It will drive prosperity, education and women's empowerment. Being delivered under PNG's leadership through the #PNG Electrification Project pic.twitter.com/arZ5S9z1Bu

— Bruce Davis (@AusHCPNG) April 6, 2019

The agreement was heralded as a “true partnership” between PNG and its key partners; aligned with PNG’s plans and priorities and delivered through existing structures – including the existing state-owned provider, PNG Power Limited.

Australia will lead the partnership, and Prime Minister Scott Morrison took time to highlight the principles that will guide its work. In a statement, Morrison said:

The Papua New Guinea Electrification Partnership is intended to focus on the importance of principles-based, sustainable infrastructure development that is transparent, non-discriminatory, environmentally responsible, promotes fair and open competition, upholds robust standards, meets the genuine needs of the people of Papua New Guinea and avoids unsustainable debt burdens.

In the context of China’s growing influence – and interest – in funding big scale projects, that language was particularly pointed. And you don’t have to look far to see the types of deals that the partnership has in its sights.

PNG’s government wants to develop the Ramu-2 hydroelectric project in the Eastern Highlands – its output is slated to be prioritised for big mining developments in neighbouring Morobe and Madang provinces. Work is slated to commence soon led by a consortium headed by the Shenzen Energy Group from China, to be delivered under a Public-Private Partnership over 25 years in a deal reported to be worth up to US$2 billion.

PNG’s opposition says the Chinese involvement in that and other projects already has some of the Partnership members – notably the US – worried about their agreement – although that has been denied by the Partnership countries. It prompts the question of what the Partnership will be investing in.

The Asian Development Bank has been the biggest international donor working with PNG to achieve its long-term electrification goals. Through programs targeting electricity supply in regional towns, the national capital and provincial centres, it has been working with PNG Power on designing and funding upgrades tied to social outcomes.

As an example, the 2017 concept plan for the ADB’s Power Sector Development Investment Program had aimed to lift electricity connection to 19% by 2029, building more than 1200 kilometres of new high-voltage transmission lines and 1600 kilometres of distribution network as part of a ten year investment program.

It’s feasible that some of that work could be taken up by the PNG Electrification Partnership and its members.

But large scale investments may not be the cheapest or most effective pathway to achieving PNG’s 2030 electrification goals. A 2015 report prepared for ANZ Bank considers the challenge by bringing in most recent understandings of renewable, off-grid and micro-generation technologies.

Author Grant Mitchell points out that because 80% of PNG’s population lives in rural areas, the big hurdle in electrification will be getting power to remote population centres – villages that might have just a few hundred people.

Fully 65% of the population in those areas will need access to power if the 2030 goal is to be met.

But as new stand-alone generation alternatives become available, the case for extending PNG’s electricity network’s poles and wires weakens. And the economic case for big scale investments in big generation projects – like multi-billion-dollar hydroelectric dams – might also be questionable.

Mitchell’s analysis suggests that for villages with populations of less than 2,000 people, unless they are within five kilometres of an existing power line, it is cheaper to use local power generation rather than a grid connection. Larger provincial towns – he uses the example of Wewak – would need populations of more than 100,000 people or be closer than 50 kilometres to the grid to make the numbers stack up.

Both of Mitchell’s assumptions are based on using high-cost diesel to run local generators. So, as wind, solar and small-scale hydro become cheaper, local generation instead of the grid becomes even more attractive. Mitchell’s report also contemplates the big infrastructure investments on the generation side that will be needed to meet an estimated tripling of national electricity demand.

Mitchell says it is only at large scale that expensive investments such as hydroelectric dams become cost-competitive against other generation technologies. And even those investments struggle to compare where loads grow incrementally over time. He points out that additions of gas generation capacity when it’s needed can achieve the same results as large scale hydro at similar costs, and without the difficulties of capital and land acquisition.

Which points to the challenges facing all the key decision-makers when it comes to electricity.

The monopoly state-owned provider, PNG Power, will be central to whatever happens. Its CEO Carolyn Blacklock has been positive about what the Partnership will mean, and how it can help her organisation to lock in financing for big investments.

The minister responsible for her state-owned corporation, the Energy Minister Sam Basil, says the government has work to do to get its policy and governance framework in place to deliver the National Electrification Roll-Out Plan (NEROP). He’s pushing ahead with the creation of a National Energy Authority to oversee the industry’s development, which may include new private generators.

And the potential investors – Australia, the US, New Zealand and Japan – need to think about what they want to do to help PNG to achieve its electrification goals. A delegation of stakeholders from the Partnership nations are visiting PNG over coming days to start to think about what they want to do next.

Having committed themselves so publicly to the big ambitious electrification goal, they have limited time to get started if they want to reach the target.