From trade to cyber, from the South China Sea to outer space, strategic rivalry between the United States and China is shaping the international order. The polar regions seem no exception.

At the recent Ministerial Meeting of the Arctic Council held in Rovaniemi, Finland, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo delivered a speech where he did not mention climate change, although he did on a number of occasions dismiss China’s claim to have a role to play in the Arctic as a self-proclaimed “near-Arctic state”. A month later, the US Department of Defense Arctic Strategy made clear that in America’s eyes, China (along with Russia) poses a challenge to the existing order in the Arctic.

The US statements followed China’s publication in 2018 of its first ever Arctic Policy White Paper. This declared China adhere to existing international law applicable to the Arctic in its ambition to build a “Polar Silk Road” as part of a larger Belt and Road Initiative. This ambition appears to have driven recent action by the US to allocate millions of dollars to fund three new “Polar Security Cutters” (icebreakers) for the US Coast Guard, to be delivered in 2023. Donald Trump’s seemingly outlandish offer to buy Greenland may have even been a further signal to China that the Arctic is a strategic zone for the US.

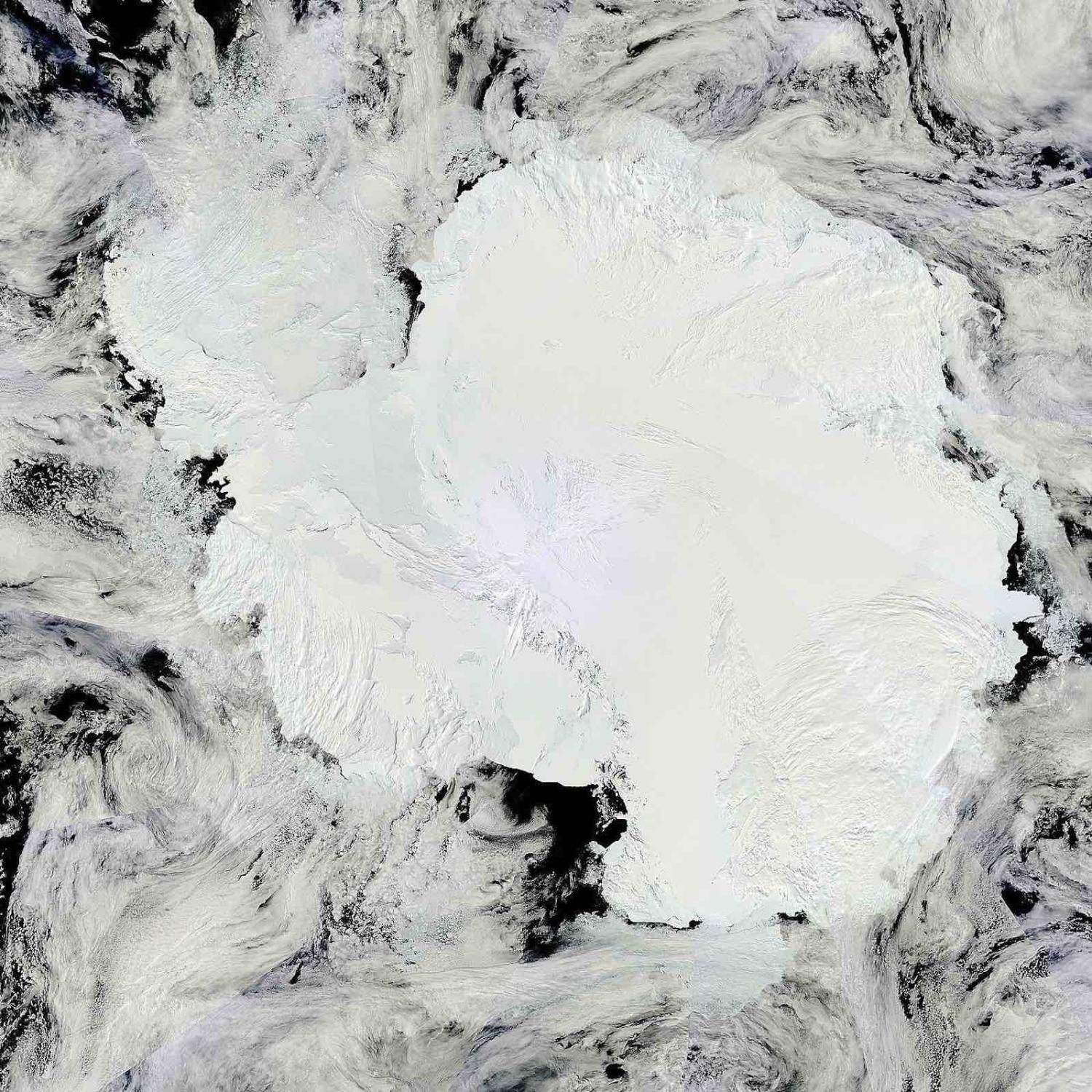

If the Arctic is now a contested arena, what about Antarctica? This near-pristine continent has been solidly governed by the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) for peace and science more than 60 years. But amid all the talk of “great power competition”, it is clear these shadows extend to Antarctica, too.

For many years, the US has been a mainstay of Antarctic governance. The Antarctic Treaty was, to certain extent, an American initiative in the Cold War to contain the expansion of Soviet Union, and hence became part of what is now regularly referred to as the rules-based international order, anchored by the United States after the Second World War.

The ATS has proved resilient and remains so. Unlike the Arctic Council, the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM), the decision-making body for Antarctic affairs, is attended by civil servants, rather than politicians or ministers. This mechanism facilitates consistent and technical work on Antarctic matters with less political influence.

Most importantly, a strength of the Antarctic Treaty is to neither deny nor accept any claim to sovereignty. But while this helped ensure territorial competition remained in the deep freeze, so to speak, it also serves China’s interests – especially a relatively recently industrialised and wealthy China.

Compared to the Arctic, the US-China competition in Antarctica is presently at its early stage, and that is a credit to the existing treaty system.

The ATS provides a peaceful and stable strategic environment, which guarantees China’s free access to Antarctica for scientific research. For example, apart from an obligation of conducting environmental impact assessment, under the Antarctic Treaty there is no legal obstacle to prevent Beijing from building research stations anywhere on the continent.

China now operates three research stations in the Australian Antarctic Territory, including the Kunlun Station in Dome A – the highest point of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. By 2022, China intends to have constructed a fifth Antarctic Station in the Ross Sea region, meaning it will boast three year-round stations, the same as the United States.

Access to resources could drive further competition between the US and China. The guiding principles of Chinese Polar activities are professed to be “Understand, Protect and Use”. This inevitably leads to questions regarding the balance between protection of the environment and the use of resources. This could test the ATS in future as countries vie for influence.

The establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) in the Southern Ocean is also a testing ground for emerging competition. Albeit reluctantly, China has supported the United States-New Zealand joint proposal to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) in the Ross Sea region, while still being concerned about the campaign for Southern Ocean MPAs, which may limit commercial fisheries opportunities in the future.

Mining is another contentious issue. Although mining is banned by the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol), this ban is subject to a potential review in 2048, and debate around the issue of protection versus use may then re-emerge.

None of this is to suggest the ATS is soon to collapse. Compared to the Arctic, the US-China competition in Antarctica is presently at its early stage, and that is a credit to the existing treaty system. But what could be a game changer is a perception by the United States, as the most powerful state in Antarctica, that China’s expanded activities on the continent pose a threat, even should Beijing follow the current rules.

There is reason for hope. In the Arctic, even after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, when relations between Russia and the West had fallen to their lowest point since the collapse of the Soviet Union, American and Russian delegations still worked together towards the adoption of the 2018 Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean. And with climate change the most imminent threat to Antarctica, this should be a powerful motivator to sweep aside national competition and work together to ensure a peaceful and stable Antarctica, in all countries’ interests.

This article is adapted from a working paper “The US-China Trade War and the Future of International Polar Law”, to be presented at the 12th Polar Law Symposium, Hobart, 1-4 December 2019.