Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang's visit to Hungary for the sixth China-Central and Eastern Europe Countries (CEEC) Summit last week demonstrates that China has become an increasingly important player in the post-Soviet space. Its presence in Central Asia is now an undeniable fact, but less well-known is its rapidly growing presence at the other end of the former Soviet empire, in the heart of Europe.

Notwithstanding China's historical ties with central and eastern European countries following the Sino-Soviet split, China's push into the heart of post-communist Europe is relatively recent. In 2011, while in Budapest, former premier Wen Jiabao proposed that ten EU members (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Romania and Bulgaria) and six non-members (Croatia - which became an EU member in 2013 - Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia) deepen their cooperation with China in five main areas: trade, investment, infrastructure, finance, and people-to-people relations. A year later in Warsaw, Wen launched the platform officially named the 'Cooperation between China and the Central and Eastern Europe Countries' or '16+1' framework to formalise cooperation in these areas. The 16+1 Secretariat is located within the Chinese Ministry of Foreign affairs.

Beijing has managed a commendable tour de force in herding together a group of heterogeneous countries that have little in common, except perhaps their communist past. Taken together, these 16 countries constitute a body that divides Europe along a north-south axis, separating Europe's established liberal democracies to the west from post-communist countries to the east. The re-creation of what looks like an eastern European bloc under the auspices of a communist great power is an admirable historical irony.

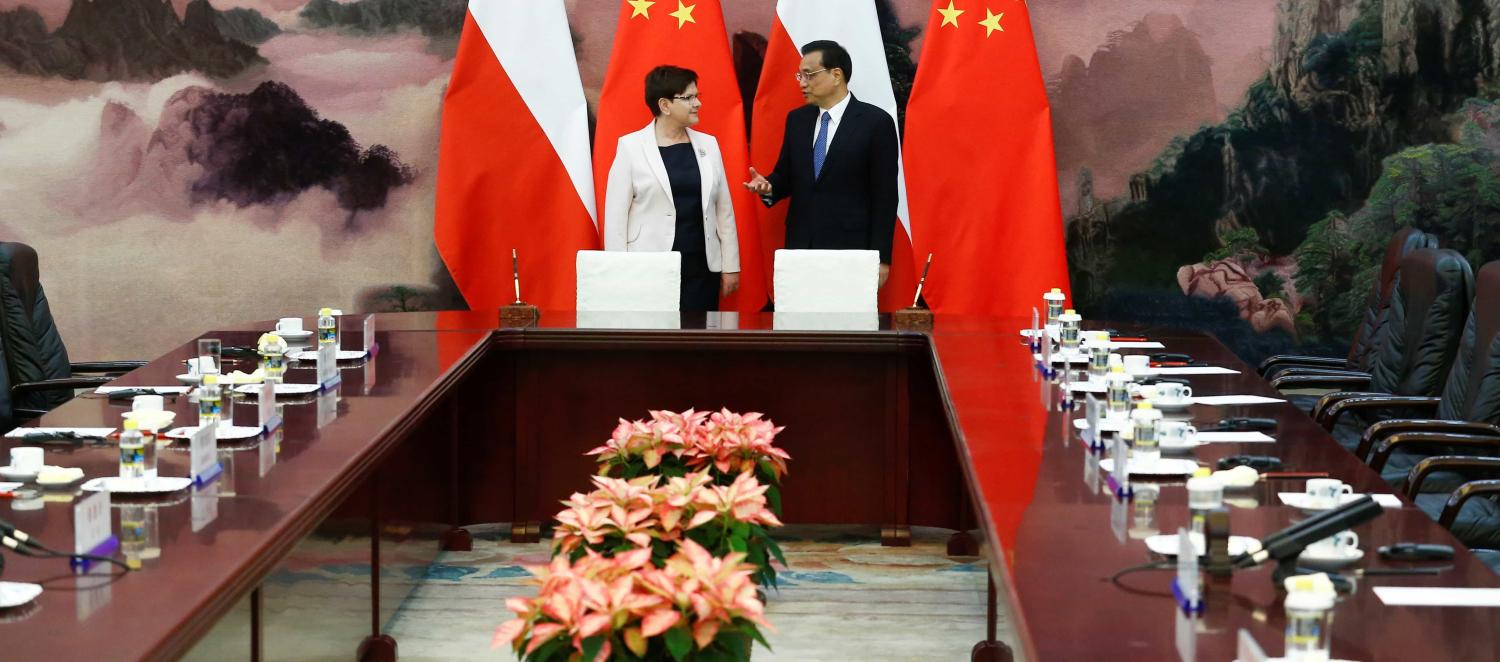

As on the rest of the Eurasian continent, the shadow of China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) looms large in China's dealings with central and eastern European countries. Quite naturally, the 16+1 format has been subsumed under the Belt and Road banner since 2013: the areas for cooperation identified back in 2011 are in fact the same as those BRI purports to promote. In typical fashion, local countries are now competing against each other to become Beijing's new 'gateway to Europe', as if China did not already enjoy multiple highways (literally and figuratively) to access EU markets and technologies. Poland, Hungary and Slovakia are the first central European countries to have signed BRI-related memoranda with Beijing.

Despite China's recurrent promises of financial largesse, the creation of a dedicated state fund in 2016 and the creation of a permanent secretariat for the promotion of investment in the CEEC established in Warsaw in 2014, Chinese direct investment in Europe remains mainly focused on advanced industrialised countries such as France, the UK and Germany, and is comparatively modest in central and eastern Europe.

But for those countries, there is more to gain from cooperating with China than just money. Some of them now face a rise of nationalism and populism and have become increasingly critical of European values. While these countries sometimes share with Moscow a common repugnance for what is seen as Western 'decadence', they are inhibited from cooperating with Russia because of historical grievances and suspicions. China, on the contrary, does not appear as an immediate security threat. China offers cooperation without political pressure, lectures on the deterioration of democratic values, or demands related to the accommodation of Syrian or Libyan refugees. It presents an inspiring model that combines state-led economic success with political authoritarianism, 'a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence' as Xi Jinping put it during the 19th Party Congress.

For those who would like to see liberal democracies flourish, it is disturbing that countries which rejected the Iron Curtain and enthusiastically threw themselves into Europe's welcoming arms after 1989 would now be lured by the sirens of socialism - albeit, this time around, 'with Chinese characteristics.'