The recent visit to Canberra by French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna put the seal on the determination of both Australia and France to forge a partnership that transcends the controversies of AUKUS. But in doing so Australia needs a clear understanding of France’s regional imperatives. France’s Pacific and Indian Ocean Island territories lie at the core of its Indo Pacific Strategy and a France-Australia partnership will almost inevitably involve these islands in different ways. Some in Australia may be tempted to see the French territories as just post-colonial holdovers. But the story is much more interesting than that.

France prides itself in being an Indo-Pacific power. It leads the Indo-Pacific strategy of the European Union and is the only European country with Indo-Pacific territories, which includes five major territories with some two million people and numerous uninhabited islands. These drive France’s political and economic interests and its substantial regional military presence.

I recently visited the French territory of Mayotte to take the temperature and discuss local security priorities. One of the first questions I was asked how an Australian even knew that Mayotte existed. I laughed, but it was a fair question. It’s a tiny group of islands in the Mozambique channel in the farthest reaches of the Indian Ocean, and indeed, only those with eagle eyes would spot it on a map.

A geopolitical analysis of Mayotte would point to its “strategic location” in anchoring France’s interests in the Mozambique Channel, one of the busiest shipping routes in the region, and potentially one of the biggest sources of offshore oil and gas in the world. Perhaps – but such an analysis would probably miss the most important reasons why France is there.

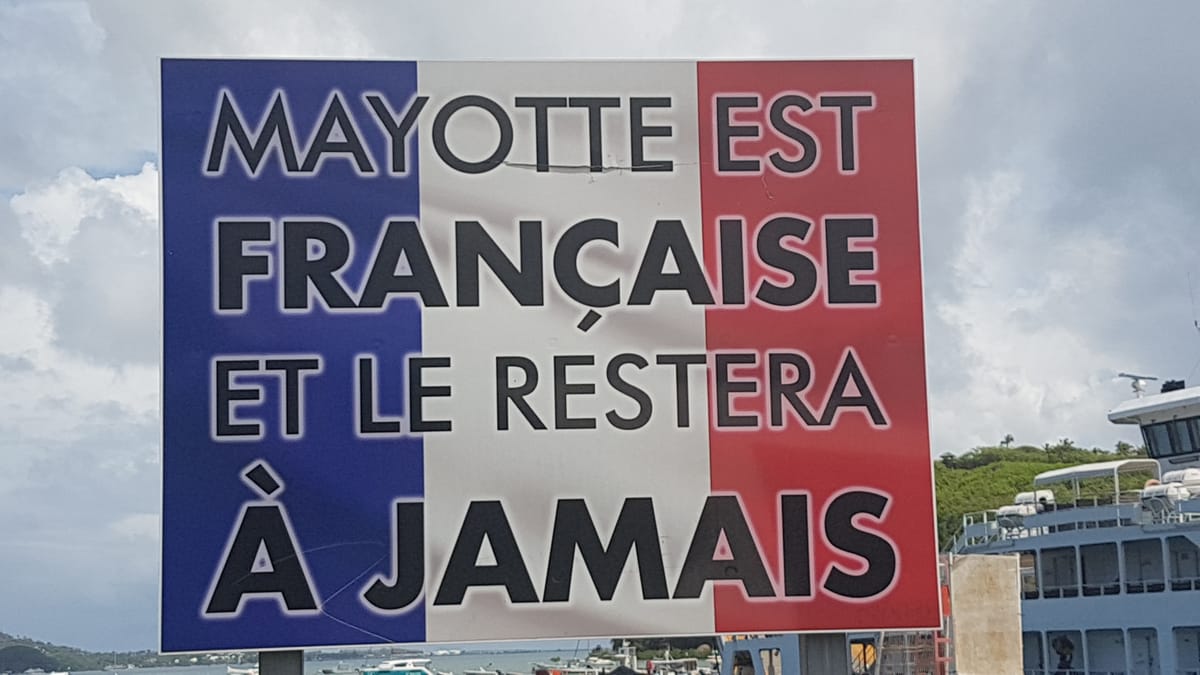

Mayotte is a wonderfully picturesque group of lush, green, volcanic islands rising steeply out of the sea – the two main ones helpfully called Grande Terre (Big Island) and Petit Terre (Small Island). Mayotte’s people, the Mahorans, are just as extraordinary, with a rich mix of Arab and African backgrounds. Their local language is a melange of Swahili and Malagasy, with a hint of Portuguese. But most of all Mahorans are French, and they want to stay that way … forever.

Along with La Reunion, which sits to the east of Madagascar, closer to Australia, Mayotte is a “department” of France. Officially at least, it is as much an integral part of France as Paris is. But Mayotte is also the poorest department of France and probably the poorest part of Europe.

As one might imagine, a piece of France off the coast of Africa has a tangled history. In 1841, Mayotte’s last Sultan, fearful of domination by neighbouring kingdoms in Madagascar and Comoros, asked for French protection, which gave the French the excuse to move in. In the late 19th century, after having administered Mayotte for around 50 years, France forcefully took over neighbouring Madagascar and Comoros.

France’s Indian Ocean empire lasted till the 1960s and 1970s, when Madagascar and Comoros gained their independence. But in contrast to its neighbours, in two referendums held in 1974 and 1976, the Mahorans voted overwhelmingly to stay part of France. They saw their destiny as quite different from other post-colonial peoples around the world.

In 2009, another referendum was held to confirm Mayotte’s constitutional relationship with France, with Mahorans overwhelmingly voting by some 95% to become a French department. This meant rejecting the status of a French overseas territory like New Caledonia or French Polynesia, which came with greater political autonomy and but also greater financial responsibilities. Instead, Mayotte elected to become an integral part of France, for which the French government has direct financial responsibility.

But this decision wasn’t just about the financial benefits. It was principally about the Mahorans guaranteeing their Mahoran and French identities.

Mayotte’s relations with Paris is not without friction. There is a feeling that Paris is too sympathetic to the needs of large numbers of illegal immigrants from Comoros, who receive free education and health care. They also resent that Mayotte is treated as a second class compared with its sister department, La Reunion, which Paris unofficially sees as its regional capital in the Indian Ocean. As local leaders like to remind “recalcitrant” officials from Paris, Mayotte has been French since 1841 – before even the city of Nice was annexed to France – and they expect to be treated as such.

This French destiny has never been accepted by neighbouring Comoros, which claims Mayotte as its own. This complicates Mayotte’s regional relationships. Mayotte can’t join the African Union and it has also been vetoed from membership of the Indian Ocean Commission, the regional grouping of Indian Ocean islands. Flight connections between Mayotte and its neighbours are sparse.

Mayotte’s status as a French department also complicates its security. When I asked Mahoran officials to list their top three security concerns (illegal fishing? drug smuggling? China?), the answer was “migration”, “migration” and “migration”.

Mayotte is the favoured destination of illegal migration from poorer neighbours, the great majority from Comoros but increasingly also from Sub-Saharan Africa. They seek a better life, access to French social welfare and a European passport. The official population of Mayotte is some 320,000 people, but the real number may now be more than double that.

The Comorans come in small fishing boats and are supposed to be detained before being deported, but that hardly makes a dent. Mayotte’s hospitals are kept busy with visiting Comoran women giving birth, thus giving their babies a priority path to citizenship.

Mahorans now comprise less than half of Mayotte’s total population. Although ethnically related to Comoros, the Mahorans feel that they are being swamped by their larger neighbour with permanent impact on their demography.

A host of consequences stem from this migrant influx. Considerable friction arises between the different communities, including frequent riots by young Comoran males. Mahorans blockade the building new hospitals and schools, which they see as attracting more Comorans. The growth in population has created significant environmental pressures, with Mayotte’s capital, Mamoudzou, experiencing regular water stoppages. For Mahorans, illegal immigration represents an existential threat.

France provides generous aid to Comoros, including building its maritime security capabilities in the hope that Comoros will stop the flow of migrants. But Comoros authorities have little incentive to stop too many boats. Comorians in Mayotte send a lot of money home, and in any event, isn’t Mayotte just part of Comoros?

France’s relationships with its Indo Pacific territories are dynamic and evolving, and it’s important not to assume that they are just colonial relics. In the case of Mayotte, the Mahorans have chosen France in order to maintain their identity. But this destiny also has its own complications. This includes dealing with neighbours that may publicly reject the Mahorans’ choice while also leveraging it for their own benefit.