In May, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution to include an item about “the Responsibility to Protect” on the Assembly’s annual agenda. On one view, the resolution is not a big deal. There are more than 100 standing items on the annual agenda, on topics ranging from counterterrorism to sport for development and peace.

The UN Secretary-General has produced a report on the Responsibility to Protect, also known as R2P, every year since 2009. Nonetheless, supporters of R2P viewed Resolution 75/L.82 as a major triumph. R2P sceptics viewed it with dismay. This is because in the topsy-turvy world of international law, resolutions are like magical spells. If enough states say the same thing enough times, words can sometimes become reality.

The problem with a reality that includes R2P is that no one is sure what it looks like. There has been forceful advocacy for its implementation on several occasions, but only once has the principle been applied.

The principle of R2P was developed in the early 2000s, in the wake of genocides in Rwanda and Serbia. Those atrocities called into serious question the capacity of the United Nations to fulfil its most basic post–Second World War mandate – to preserve peace and prevent the destruction of entire peoples. In Rwanda, UN representatives were on the ground before the massacres began and gave clear warnings about which way the winds of atrocity were blowing. In Serbia, genocide took place under the watch – literally – of UN peacekeeping forces. When NATO forces intervened in Kosovo to prevent widespread death and destruction, they were accused of breaching the UN Charter by using force without Security Council approval.

While critics of R2P point to inconsistency, hypocrisy and the likelihood of economic rather than humanitarian reasons underpinning the application of R2P, its proponents point to the fact that the principle stands for more than intervention.

Against this backdrop, then–Secretary-General Kofi Annan in March 2000 asked this question in what came to be known as the Millennium Report: “If humanitarian intervention is, indeed, an unacceptable assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a Srebrenica – to gross and systematic violations of human rights that affect every precept of our common humanity?”

In 2005, an Independent Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty answered Annan’s question in a report authored by a constellation of eminent political figures, including Australia’s former foreign minister Gareth Evans, Michael Ignatieff, who went on to become Canada’s opposition leader, South African politician and current president Cyril Ramaphosa, and former Philippine president Fidel Ramos. The report concluded that military intervention to prevent large-scale loss of life and ethnic cleansing was justified, as a last resort, when states failed in their most basic duty to protect their own populations. The Commission concluded that states seeking to intervene should seek Security Council authorisation; and that the Permanent Five members of the Council, who hold veto power, should not obstruct the passage of resolutions for military intervention for humanitarian purposes.

Following the outcomes of the 2005 UN World Summit, these principles eventually became cast into three “pillars”:

- Every state has a responsibility to protect its populations from four mass atrocity crimes: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing.

- The wider international community has the responsibility to encourage and assist individual states in meeting that responsibility.

- If a state is manifestly failing to protect its populations, the international community must be prepared to take appropriate collective action, in a timely and decisive manner, in accordance with the UN Charter.

Gone was the earlier suggestion that intervention without Security Council authorisation might be permissible in circumstances where the Council failed to act in a timely way. Gone also was the suggestion that the five permanent members of the Security Council should refrain from exercising their veto in humanitarian cases.

Libya remains the only case where R2P has been implemented. In February 2011, Muammar Gaddafi responded to anti-government protests by proclaiming he would “cleanse Libya house by house” of protestors and that his supporters should attack the “cockroaches” who were demonstrating against his rule. In what Gareth Evans described as a “textbook case of the R2P norm working exactly as it was supposed to”, the Security Council authorised the use of force by NATO to prevent mass murder in Benghazi.

In Syria three years later, when President Bashar al-Assad made similar threats to quell the Arab Spring by murdering his own population and then used chemical weapons in a suburb in Damascus, there was a view that military intervention might do more harm than good. Regardless, there is little doubt Russia would have used its veto in the Security Council against any such proposition.

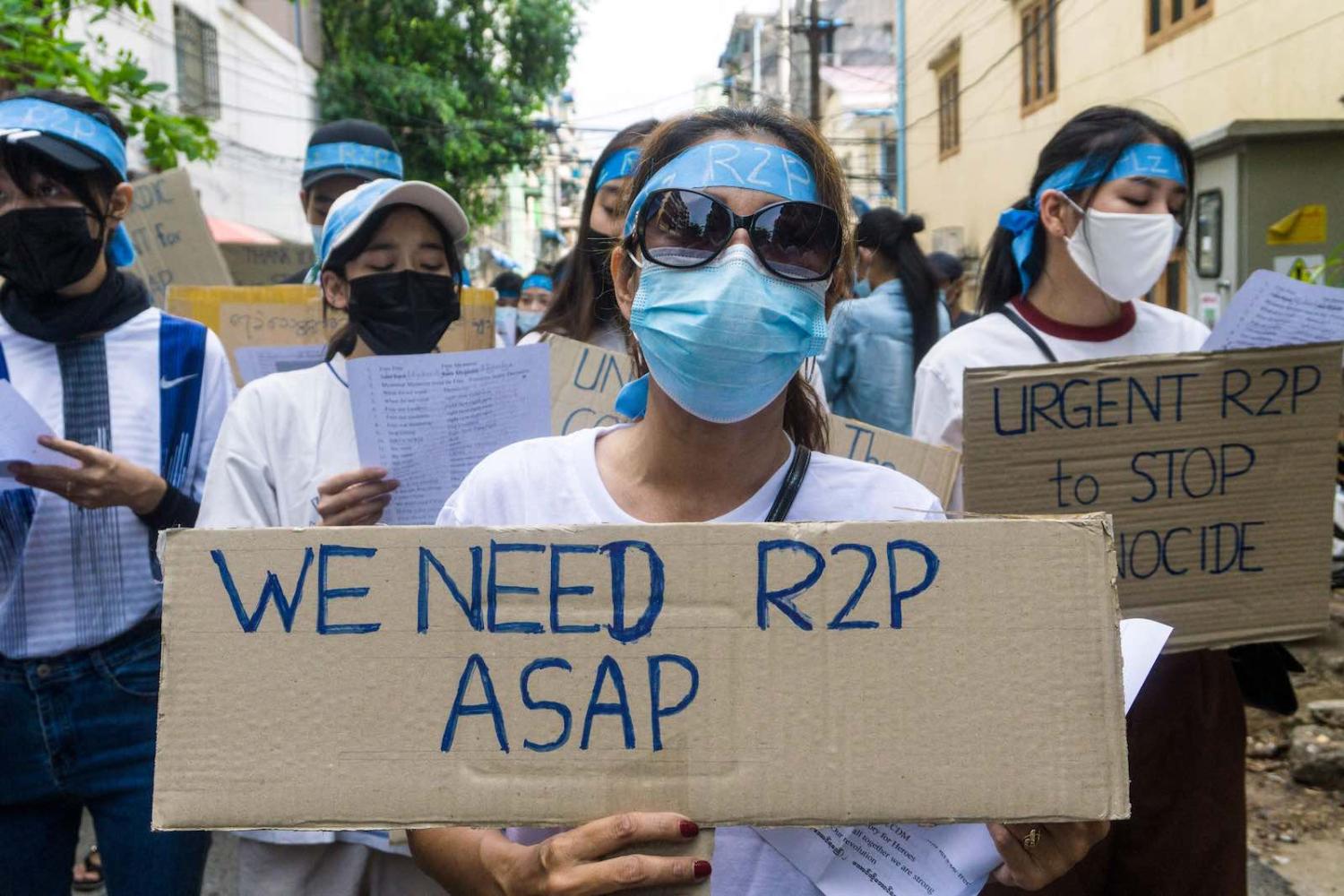

Most recently, the beleaguered state of Myanmar has emerged as a potential site for R2P intervention. On 1 February, a military coup overthrew the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi, leader of the National League for Democracy. The people of Myanmar responded with widespread and peaceful protests. They were met with machine-gun fire, mass arrests and the death of more than 700 civilians. Again, Evans described the situation as one that “unequivocally demands the application of R2P principles”. Once again, however, there were serious impediments to the principle’s implementation. How could military intervention be effective in a country that is bigger than France, and that lies between China and India? Why would India and China, both sitting on the Security Council, agree to intervention when both sell arms to Myanmar’s military?

While critics of R2P point to inconsistency, hypocrisy and the likelihood of economic rather than humanitarian reasons underpinning the application of R2P, its proponents point to the fact that the principle stands for more than intervention. It is, they argue, a reminder to states they have a responsibility to protect their populations, rather than slaughter them. And it is a reminder to the international community that it has a responsibility to help states fulfil their obligations.

The problem is that when these reminders matter most, they are least likely to be heeded – we can reference here Myanmar’s generals and its closest neighbours. Resolution 75/L.82 will not change this reality. It will sit on the annual agenda of the UN General Assembly like “the Question of Cyprus” and “the situation in Afghanistan” – as a recurring sign of the noble reach but limited grasp of the United Nations.