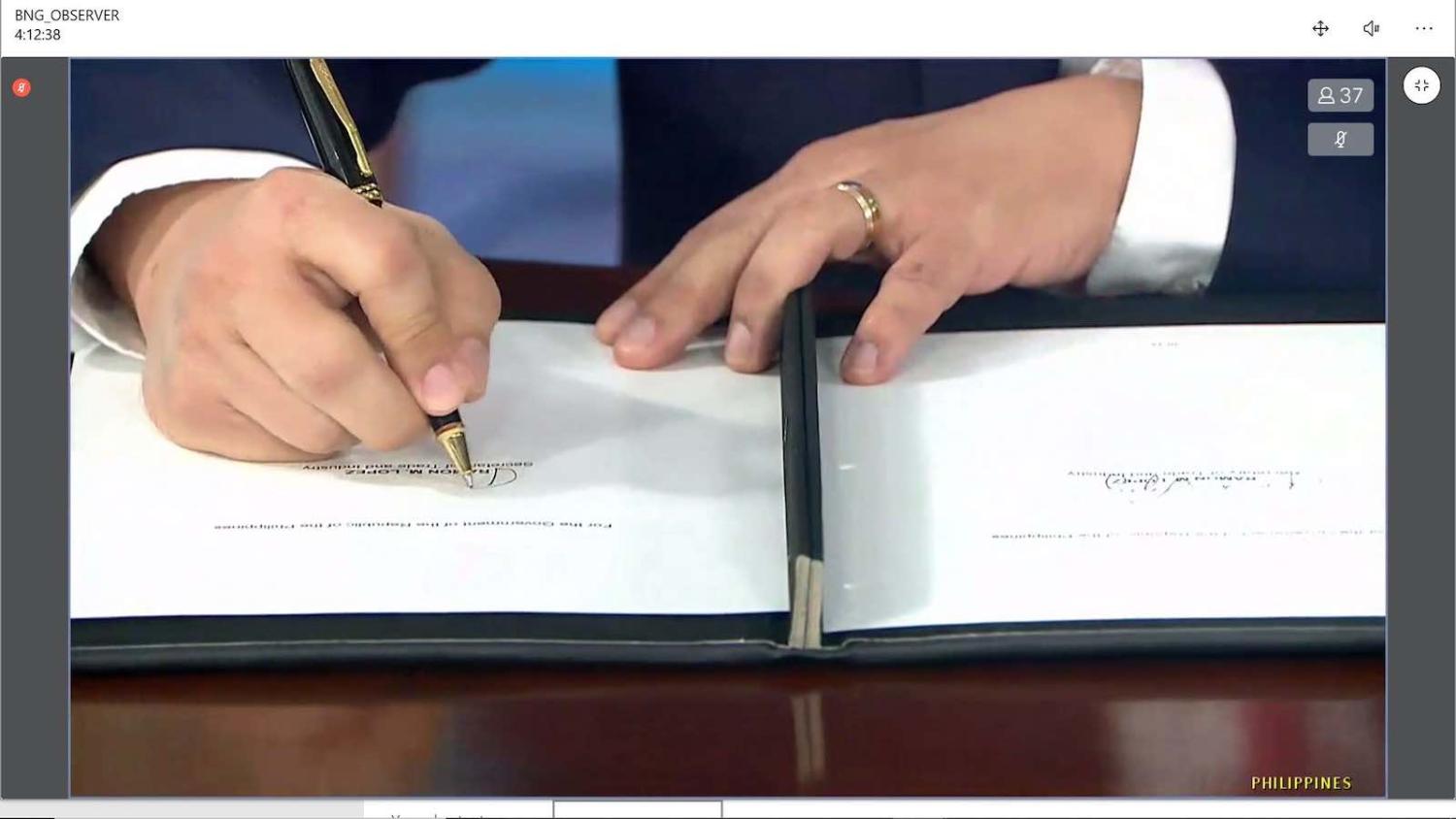

News that 15 governments had signed the text of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement did not force either Covid-19 or the presidential transition in Washington off the front pages. It probably attracted the attention it did because it was a virtual signing ceremony – a super Zoom meeting of leaders in the Asia-Pacific region.

In these times of continuing economic turmoil, where the signs of downside risk to the global economy are much more prevalent than stories of upside growth, the rather bored reception that RCEP got was not surprising. Particularly as ratification by each signatory is necessary to bring the text into force for their jurisdiction. The agreement, which includes the 10 ASEAN nations plus Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea, will take effect when three non-ASEAN and six ASEAN members have duly ratified.

Why the bored reaction? In part because it has been a long time in coming (negotiations began eight years ago). Second because it does not seem to offer much that is new in the trade policy world. Third because India is not a signatory, and the US is excluded from another trade agreement in Asia. And fourth because the concrete gains seem small. (The New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade says, for instance, “RCEP does not therefore deliver significant new market access for goods exports as a result of tariff cuts”.)

Another reason for scepticism is that in the real world, trade agreements do not seem to have much bite anymore. Australia, which has a bilateral free trade agreement with China, is experiencing trading difficulties which such an agreement would normally mitigate, if not resolve amicably. The European Union–United Kingdom Brexit negotiations are also not a shining light of modern-day practice.

And the United States is nowhere to be seen. So the strategic question of how the world’s largest economy fits into the framework is not answered. Those hoping for a better world under Joe Biden may have to wait a while yet.

Still, you have to look a bit more deeply. In terms of geographical coverage, RCEP goes even further than the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), so it does offer a bigger grouping than any other. India is staying outside it, but there are those who would say that that is better than India inside it.

In practical terms, its biggest achievement is on rules of origin, that arcane term which often makes trading flows difficult. Under RCEP, there will only be one qualification for all trading partners: any product produced from materials originating in the area will be acceptable all over. No longer will an exporter in Australia have to worry whether parts from Malaysia qualify for goods going to South Korea, for instance. Given that rules of origin were at the heart of the North American Free Trade Agreement renegotiation, and are at the heart of the Irish issue in Brexit, this is real progress.

There are also modest improvements in areas such as transparency, documentation, investment, geographical indicators and cutting of red tape. Clearance of perishable goods gets some priority as well, which suits exporters such as Australia and New Zealand. Not shattering, but worth having.

Let us in these times of protectionism and nationalism offer some thanks that trade liberalisation is not totally dormant.

Under the cover of RCEP, China, Japan and South Korea are for the first time together in a free trade area. This was a target of direct negotiation some 15 years ago, but it proved too difficult for the three of them to do. Now it will have real consequences.

And, finally, there is now a framework that offers new supply chains across East Asia and the Pacific, as global manufacturing reassesses both the risk of too many eggs in the China basket and the potential effects of home-shoring.

With regard to China, it is now party to a multilateral agreement of substance to make up for its exclusion from CPTPP. The new agreement is not, for all that, a China-led initiative. It flows from work done for many years by ASEAN, in the ASEAN Plus Six framework.

There is the tantalising question of what the United States will make of all this. Clearly, a Biden administration is not going to reverse completely Trump trade policies, particularly given the hostility of parts of the Democratic vote. But it will not contemplate with indifference the absence of the US economy from both CPTPP and RCEP, especially as the evidence suggests that it is in East Asia and the Pacific that economic recovery from Covid-19 will be stronger.

Looking further ahead, we can see the outlines of a wider arrangement that might eventually encompass both CPTPP and RCEP. This is at present remote, but we should not underestimate the incrementalism of trade policy objectives over a longer time, particularly after periods of disruption such as the Covid-19 pandemic. Who could have thought, for instance, in 1947, that the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which had 23 signatories, could lead to a World Trade Organisation with 164 member states?

Finally, let us in these times of protectionism and nationalism offer some thanks that trade liberalisation is not totally dormant.

New Zealand, as Chair of APEC 2021, is going to have an interesting time: a global economy still suffering under coronavirus, but growth in China, Japan and elsewhere in Asia, a new US administration searching for a role and a policy, and all this being managed remotely. A big challenge.