This is the second of a series of three articles on the Rohingya crisis, featuring Morten Pederson on the domestic drivers of conflict, and Andrew Selth on the potential danger from transnational terrorist networks.

Most of the Rohingya who were forced from their homes in Myanmar last year now find themselves stuck, perhaps in perpetuity, on the Bangladesh side of the border. While there have been outpourings of material and rhetorical support from both the Western democracies and from across the Muslim world, the crisis was slowly fading from the top of the global agenda.

The release last week of a powerful United Nations fact-finding report is, in the next breath, another sobering reminder of how badly the Rohingya have been treated in Myanmar. The word used is “genocide”.

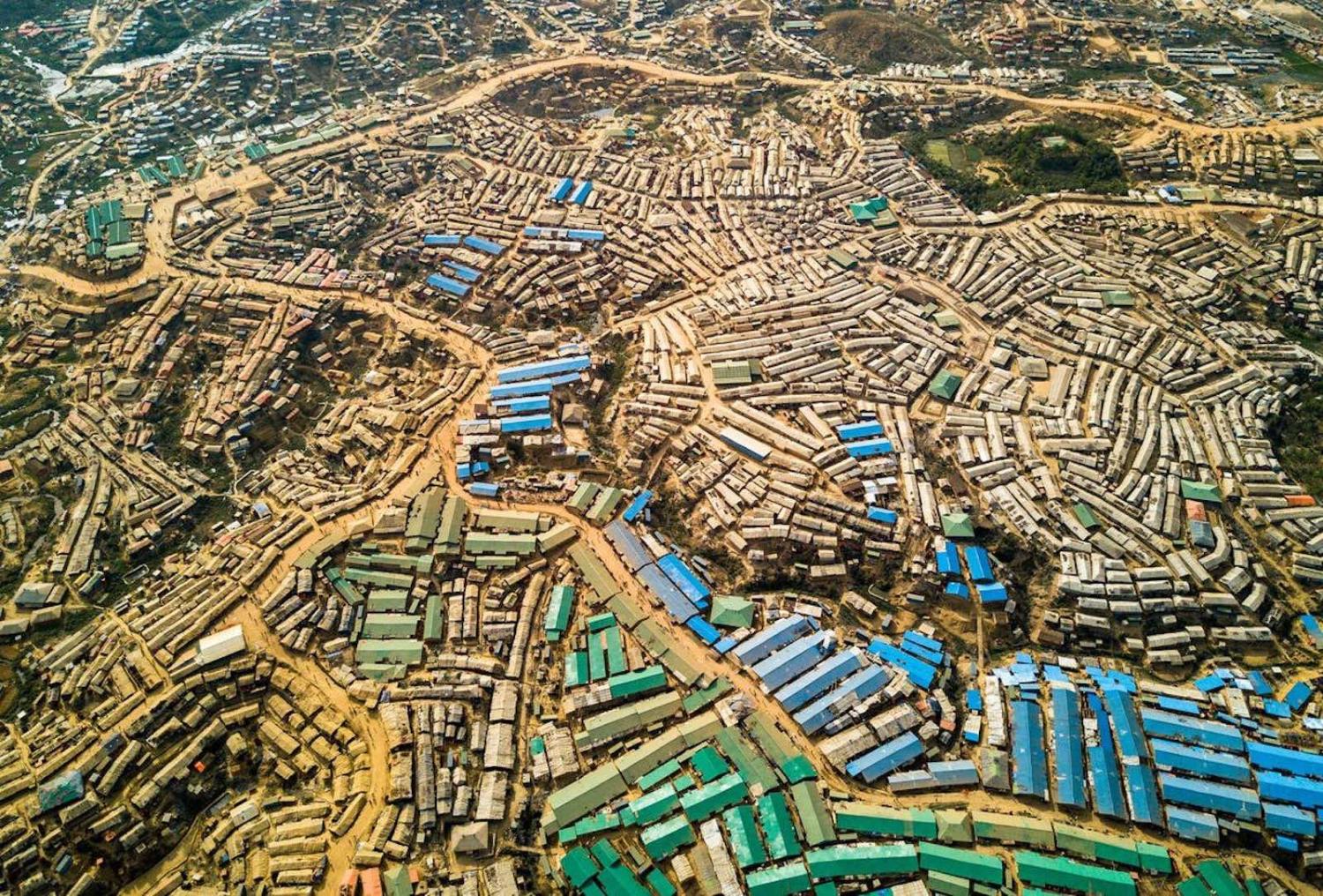

To its credit, Bangladesh’s well-entrenched government, led by Prime Minister Sheik Hasina, has made room for a large-scale humanitarian response in the region around Cox’s Bazar. Yet this does not imply comfort with what will, over time, become another economic and strategic fault line in one of the world’s most densely populated parcels of land.

There is a reasonable chance that during the next sailing season, or the one after that, Rohingya will start to move in large numbers ... It is a perilous journey and more will die.

Return to Myanmar’s Northern Rakhine State, a heavily militarised and antagonistic landscape, is not a serious option for most Rohingya. The brutal violence and rampant impunity of 2017, and the virulence of lingering anti-Rohingya attitudes in Myanmar, have condemned many of the displaced to the margins of Bangladeshi society.

Some Rohingya will eventually seek to leave by sea, air or land. Those escape routes are all constrained, to varying extents, by logistical, political and natural obstacles. Taking to small boats aiming for destinations in Southeast Asia has been a common strategy of recent years, but the regional regime targeting irregular migration adds extra layers of complexity and danger.

For their own reasons, third countries are hardly queuing to resettle the Rohingya: an impoverished, vulnerable, friendless people.

There is, as such, a reasonable chance that during the next sailing season, or the one after that, Rohingya will start to move in large numbers, probably aiming, again, for Malaysia. It is a perilous journey and more will die. But the air and land exits remain blocked for all but the most intrepid or well-resourced. Life as a labourer in the Middle East might be fit for some – but conditions in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates are still grim for those on the bottom economic rungs.

And, for now, the security situation around Cox’s Bazar remains fraught. For generations, Bangladesh’s secular, mostly socialist, ruling elite has fought a low-level civil war against their country’s own Islamists. The multi-tentacled security operation in Rohingya settlements is an effort to stomp on those looking to light the fuse of communal hatred. It was only six years ago that Buddhist villages and temples across southeastern Bangladesh were burned to the ground by rampaging Muslim mobs.

The fear is that, eventually, the Rohingya will realise that they have been abandoned by the wealthy countries of the Muslim world and will increasingly seek support from those groups that call for vengeance. Some ISIS-style extremists may want to exploit the Rohingya crisis, but, for now, security agencies have proved equal to the task.

Bangladesh is also playing a geopolitical game, and could, under the wrong conditions, undermine the fragile stability that has been imposed in Myanmar’s Northern Rakhine State. The most obvious mechanism would be to loosen security on militias, whether Muslim or Buddhist, seeking to use Bangladesh as a launchpad for further violence. Tempers, in this scenario, could fray quickly.

At the same time, there is concern in Naypyidaw, among State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi’s advisors and key security officials, that Myanmar has now vaulted up the list of targets for groups seeking to take the fight globally to enemies of Islam. An attack against Myanmar interests would change the equation quite significantly, reinforcing the need for the sternest counter-terrorist action.

Whatever happens next, dealing with the potential for such future violence is only one of the issues, and far from the most important. With hundreds of thousands of children now condemned to grow up in haphazard settlements, in the mud, with limited access to education, the consequences of the 2017 violence will reverberate for a very long time to come.

Sadly, there is almost universal social endorsement, in Myanmar, of last year’s anti-Rohingya pogrom. Spite against the Rohingya has probably only increased over the past year.

What does this all mean for the Rohingya now stuck in Bangladesh? Like the rest of us, the Rohingya need to have hope in a reasonable future for their children. At the moment many may imagine that, before long, the world will offer third country resettlement, or engineer a peaceful and sustainable return to Myanmar, or give them long-term rights to life and livelihood in Bangladesh. From what I can see, none of those things will happen any time soon.

It would take an enormous and ambitious global response to resolve this humanitarian, cultural and political crisis. Pragmatists see that there will be no easy victories.

But if hope dies for the Rohingya, we will all face more problems. Violent extremism will be one obvious outcome. Criminality and exploitation are inevitable. People movement, too. Avoiding the worst possible outcomes will require serious resources from the rest of the world and almost infinite tolerance on the part of the Bangladeshis.

And even that may not be enough to save the Rohingya from further calamity and despair.