The rules-based order (RBO) concept is a bit like the Australian property market – just when it seems to have peaked, it surges again.

The RBO has endured despite its extremely uninspiring name and the return of “great power competition”. Observers might expect that this competition would come at the expense of rules. But the RBO was invoked again and again in the latest round of US-led summits.

In its communique, leaders of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) reaffirmed their commitment to the RBO and asserted that “China’s stated ambitions and assertive behaviour present systemic challenges to the rules-based international order”. That echoed US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s earlier statement that “our purpose is not to contain China, to hold it back, to keep it down. It is to uphold this rules-based order that China is posing a challenge to.”

Where did it come from?

The RBO emerged in the early 1990s under the shadow of the “Liberal international order (LIO)” – a term that is still much more widely used.

Australian political leaders were early adopters – and pushers – of the RBO. Early in his first term, then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd deployed the term in a 2008 speech about China in Washington. Two years later, as Foreign Minister, he issued a joint statement with US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. She appears to have been the first US cabinet member to abopt the RBO.

The following chart via the Google Books Ngram Viewer shows term “rules-based order” has been used in English-language books, journals and articles more frequently since 2014, but “liberal international order” continues to be the dominant terminology.

The two terms are now often used interchangeably. Scott Morrison referred to a “liberal, rules-based order” in his speech at the Perth USAsia Centre before departing for the G7 summit. But, for the most part, Australian leaders seem much more comfortable describing the order as “rules-based” than as “liberal”. That may reflect deep-seated suspicion of American liberal internationalism, which goes back to the days after the First World War and Australian prime minister Billy Hughes sparring with American president Woodrow Wilson at the Versailles Peace Conference.

Although the RBO may sound less ideological than the LIO, a closer look at the history of both concepts suggests that the RBO was conceived in far more ambitious terms.

Capturing globalisation

The LIO really came into being during the dark days of the Cold War. It described the order that liberal democratic states created between themselves. It was international but never global. No one ever claimed that the Soviet Union was part of the liberal order.

By contrast, the RBO was coined in a wave of post-Cold War optimism. It was then widely assumed that, with the collapse of communism, it was only a matter of time before all states would come to accept the Washington Consensus, and the LIO would expand to cover the globe.

The term “rules-based order” began to rapidly overtake the phrase “rules-based trading” from 2005 onwards. It is now the most commonly used term of the two in English publications online, as this Google Books Ngram Viewer chart shows.

The RBO was almost certainly coined to describe a globalising LIO. It’s unlikely the first users were simply seeking a dull synonym for the LIO. It’s more likely they saw that – as ideologues were replaced by technocrats – the adjective “liberal” was becoming redundant.

This process was most advanced in the multilateral trade system. The Uruguay round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) negotiations that began in the final years of the Cold War led to the creation of the World Trade Organisation. The adjective “rules-based” was most often used to describe this emerging trading system before it was used to describe the global order.

An anachronism?

Viewed in this light, the RBO looks like a strange anachronism. The surge of post-Cold War optimism in which it was born now looks somewhat naïve, and at times hubristic. By daring to ask whether the End of History had been reached, Francis Fukuyama made himself the straw man for countless opinion pieces in the decades to come. But the RBO continues to grow.

Acknowledging the RBO’s history doesn’t mean that global institutions and rules don’t matter.

It grew fastest from 2014–16, most likely in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and China’s island-building in the South China Sea. The term appears 56 times in Australia’s 2016 Defence White Paper. Of those 56 references to the RBO, more than 40 refer to the global order and only three refer to the regional order.

More building, more regional

RBO rhetoric can be an obstacle to policy development and prioritisation. Defending a global RBO that may never have existed – at least not in the form that is now often claimed – is an overwhelming challenge. On the other hand, almost any policy can be justified as part of this effort. For example, the 2016 White Paper explains Australia’s military commitments outside its region, especially to the Middle East, as support for the “global rules-based order”.

Acknowledging the RBO’s history doesn’t mean that global institutions and rules don’t matter. Nor does it detract from the worthy goal of strengthening them.

But it requires a shift in emphasis away from defending the RBO and towards building an RBO – especially in this region.

The extent to which what it now called the Indo-Pacific was ever part of the LIO and, its successor, the RBO is open for debate. Post-Cold War globalisation – including of rules – has clearly played a major role in the region’s prosperity. But assertions that the rules-based global order has delivered 70 years of peace and security in the Indo-Pacific are ahistorical and unhelpful. The bloody conflicts in Korea and Vietnam may have been peripheral to the Cold War and the LIO, but they were central to this region.

The development of a more rules-based order for the Indo-Pacific remains a daunting challenge. But without a clear-eyed understanding of the RBO’s history, it will be even harder.

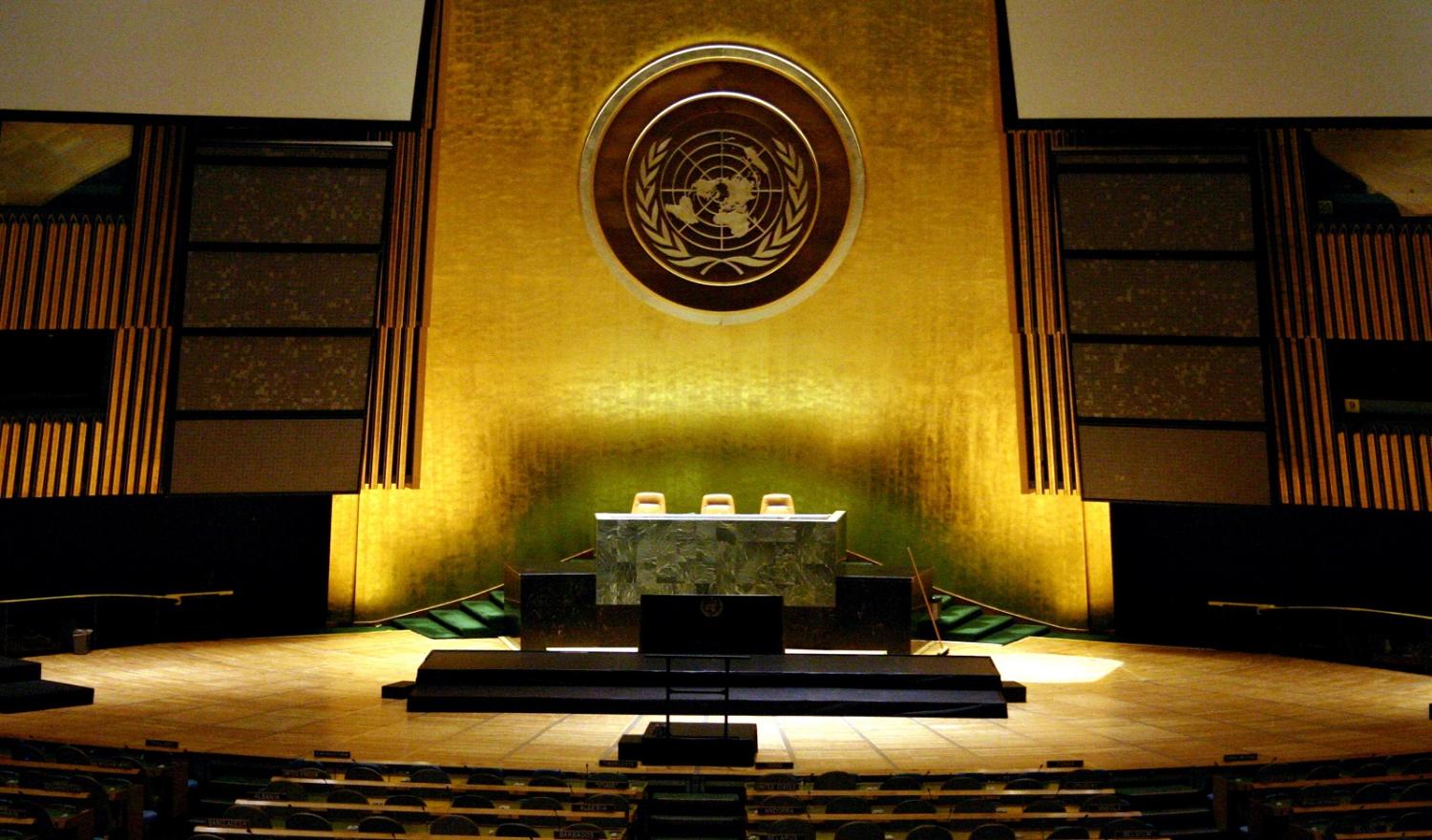

Main image via Flickr user Patrick Gruban