In 2018, when Australia shared security concerns about Chinese tech giant Huawei with allies and later banned the company from supplying equipment for the development of its fifth generation (5G) telecommunications network, it escalated a simmering row about Huawei’s presence in telecoms systems around the globe.

Since then, although Canberra’s firm stance against the company – and by proxy the Chinese government – has shown no signs of waning, the locus of the dispute has unquestionably shifted. As part of its rapidly deepening (though often inconsistent) confrontation with China, the United States in the last two years has led the campaign, encouraging countries all over the world to curb or end engagement with Huawei.

But while the quarrel has become one primarily between two superpowers on either side of the North Pacific, it has recently opened an unexpected opportunity for greater trans-Pacific integration in the Southern Hemisphere. Last month, the government of Chile announced that the route for its planned transoceanic fibre-optic cable would run through Auckland and have its terminus in Sydney.

The Chilean government left no doubt that it sees this 13,000-kilometre link to Australia first and foremost as a gateway to Asia.

Coming several years after a study carried out by Huawei that put forward three potential routes, all of which ended in Shanghai, the surprise choice is seen as a snub to China. Choosing a Japanese-proposed path with Australia as its final destination allows Chile to avoid some of the murky waters of the international confrontation. As noted by Chilean newspaper El Mercurio, while the decision comes in the context of pressure from the United States, at the same time it demonstrates “a certain independence in the face of the two hegemonic powers of the world”.

To be sure, not only does the Chile-Auckland-Sydney undersea cable sidestep some of the alleged risks surrounding Huawei and China, but it will also provide Chile and its neighbours with an alternative to the United States for Pacific telecommunications crossing. At present, all trans-Pacific fibre-optic cables land in the United States on the western side, meaning that Latin America relies heavily on US hubs for its telecoms activities with the Asia-Pacific region.

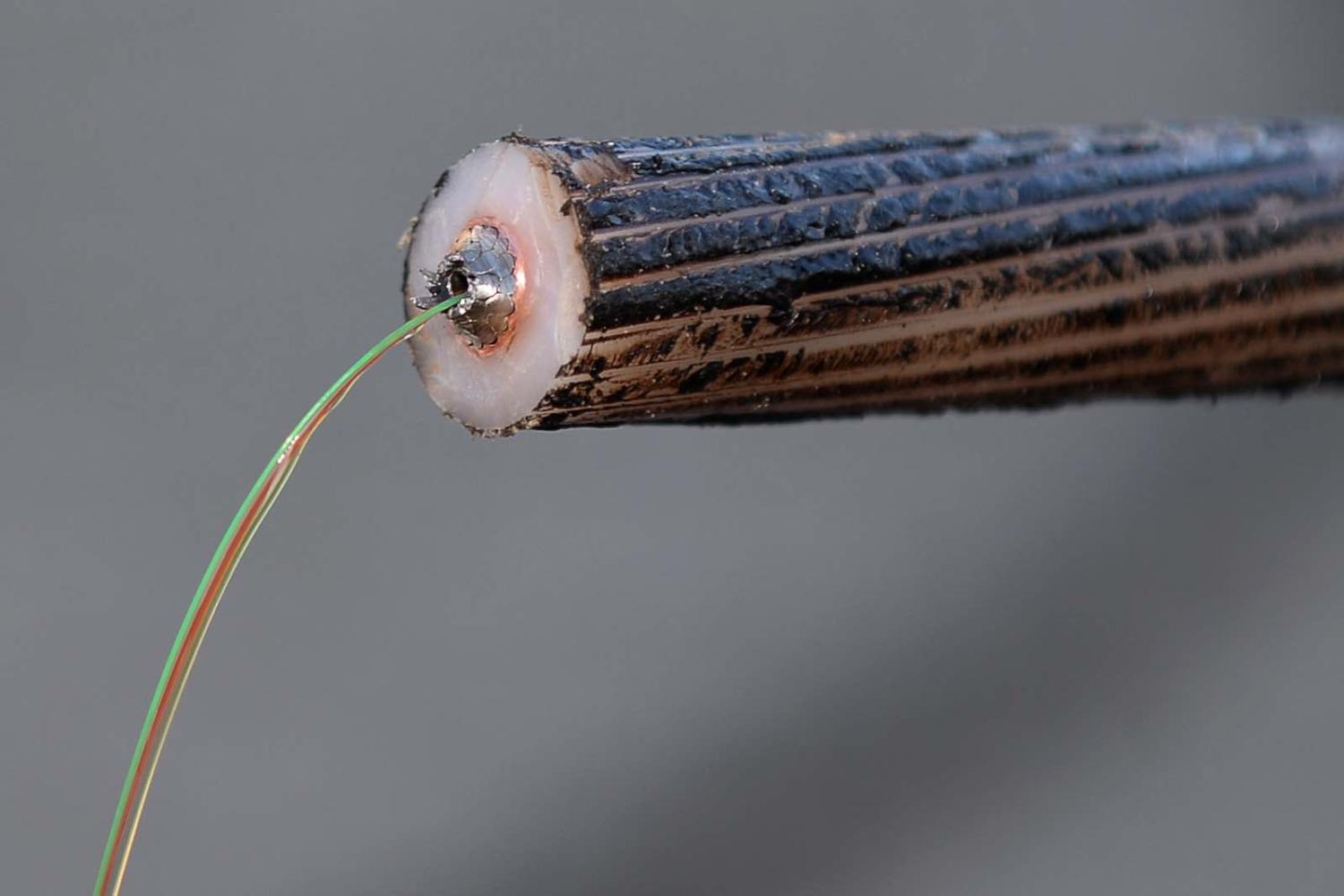

And it’s hard to overestimate the importance of these undersea connections. According to TeleGeography, a telecommunications market research company, while satellites are useful for certain applications, on “a bit-for-bit basis” cables are in a league of their own, transmitting “far more data at far less cost than satellites”. Undersea fibre-optic cables reportedly carry 95% of international communications, which includes internet data.

In announcing the decision, the Chilean government left no doubt that it sees this 13,000-kilometre link to Australia first and foremost as a gateway to Asia. Its statement called Sydney not only the digital hub of Oceania, but also an emergent hub of Asia, highlighting that Sydney has five cables that reach to the continent. Once the new cable is constructed, Chile hopes it can tap into these lines to better connect to markets such as Japan, South Korea and of course China, its largest trading partner.

But even without these Asia connections, the project holds promise for strengthening ties between Australia and Latin America. As I noted in a previous article, Latin America has been growing in economic import for Australia in recent years. Chile, for example, in 2009 became just the fifth country in the world with which Australia entered a free trade agreement, and this basis for exchange has only been bolstered through both countries’ membership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership – an accord that also includes Latin American nations Mexico and Peru.

ln addition to such agreements, the increased trade between Australia and Latin America has been stimulated by a gradual move by both sides away from their traditional reliance on exporting primary products and towards services and manufactured goods. As global commerce and trade become more and more digitised, particularly amid the potential long-term transformations brought about by Covid-19, exchange between these increasingly service-based economies could no doubt be accelerated by the new fibre-optic cable.

Nevertheless, the promise of the cable should not be overstated. Broadly speaking, the Australia-Latin America relationship remains nascent on many fronts, and telecommunications is no exception. According to Alan Mauldin, Research Director at TeleGeography, the actual usage demands for a Chile-Australia link are currently quite low. While the cable would offer favourable latency and route diversity and bring some benefits to governmental, corporate and individual consumers, Mauldin stated that “there’s a reason there is not a cable on this route already”. He noted that the project had required government involvement because private developers did not see a compelling commercial case. Construction is expected to cost about US$500 million, and contracting bids are scheduled for next year. In view of high demands on most cable suppliers in the next few years, Mauldin estimated that the cable may not be in service until after 2023.

Still, Chile’s announcement made clear that the decision arose more from a vision of the future than in response to current realities. Its statement noted that it was determined to move forward following a projection of telecommunications traffic across the South Pacific in the next 20 years. Already looking to engage neighbours such as Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay in the opportunities for increased connectivity, Chile is banking on becoming the digital hub of South America. With this digital bridge in place, Australia – as a hub itself – only stands to benefit if that vision becomes a reality.