Geography is a tricky inheritance. For most countries, fate is sealed depending on their position on the map. For some states, the hand dealt by the natural forces condemns them to mediocrity at best or being a floundering fiasco at worst. Ask the erstwhile Yugoslavia, the now-tottering Myanmar or dysfunctional Afghanistan. Geography, in these cases, is coldly tyrannical.

On the other hand, the same physical forces are a blessing for others. The United States would not be what it is without the Atlantic and Pacific as its oceanic benefactors. A safe distance, not too close yet not too far, from Europe allows the United Kingdom to pick and choose its neighbourhood battles. A favourable location entitles London to stay aloof from continental intrigues when necessary or intervene when the European balance of power dramatically alters.

However, too much of the good stuff also leads down a slippery slope. Heady internationalism, born of no direct regional threats and perceived pre-eminence, led Washington to the blunders of Iraq and Afghanistan. Woolly ideas like “manifest destiny” have long been a part of American foreign policy.

There is much that major and middle powers alike can learn from their smaller and more successful counterparts.

The situation is very different for small countries in crowded neighbourhoods. With larger states prowling in close vicinity, the margin for error is drastically thin. The Omans and Qatars of the world do not have the liberty of a United States whose mistakes are chided and forgotten. For small states, to make strategic blunders is to court oblivion.

There is much that major and middle powers alike can learn from their smaller and more successful counterparts such as Taiwan, Singapore, Qatar and Oman. The essential need is to be clinical about national interests and the state of the world. Foremost to all is survival, followed then by expanding the scope for domestic prosperity.

The quest for survival and prosperity demands small states to make themselves indispensable to larger powers that be. That is by making themselves relevant to the region in which they operate. In such cases, pragmatism entails developing strategic and economic policies in a way that all major powers have a deep stake in one’s survival. In a few words, relevance by enmeshment.

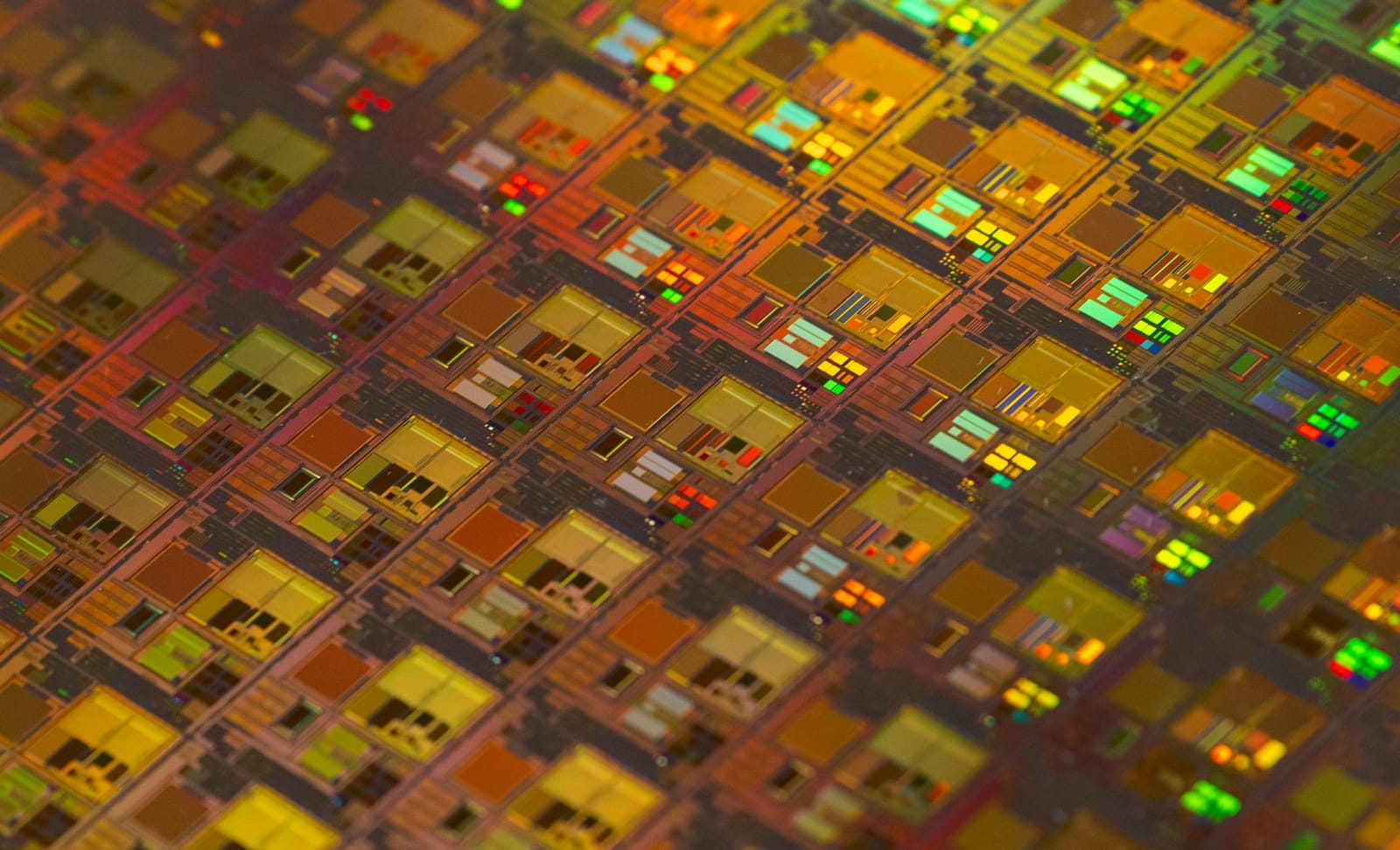

Take Taiwan for example. In the early 1970s, Taiwanese leaders grasped the impending global economic trends of rapid globalisation and the rise of electronics and advanced manufacturing. If Taipei could make itself a critical node in the global supply chains of high-end electronics, the major powers would have a stake in its survival. At the same time, advanced manufacturing could propel Taiwan’s domestic prosperity. The Taiwanese government therefore set up the Industrial Technology Research Institute in 1973, under the astute Morris Chang, providing the research base from which the semiconductor industry would take off.

Today, Taiwan produces more than 60 per cent of the world’s semiconductors and over 90 per cent of the advanced ones. For China to enter Taiwan uninvited would mean a $10 trillion heart attack for the global economy. Make no mistake – neither China nor the US want a catastrophe in Taiwan anytime soon. Such an eventuality would spell disaster for their economies. In China’s case, it could even undermine the legitimacy of the regime, threatening political change.

Singapore is another pertinent case of why not to strike off the agency of small states. Through grit and a sense of hard-nosed pragmatism, Singapore from the time of its visionary leader Lee Kuan Yew believed in the agency of small states. As an indomitable Singaporean diplomat Bilahari Kausikan puts it, his country was never to be “cowed or limited by our size or geography.”

Over the decades after its separation from Malaysia in 1965, Singapore’s technocratic and political elite have sedulously developed its relevance and usefulness as a critical node in global shipping lanes and supply chains. Even courting foreign capital in the 1960s and 70s, when regional powers such as China, India and Vietnam could not resist the addiction of misplaced protectionism, gives a taste of Singapore’s agency and counter-intuitive freshness.

Like Taiwan and Singapore, two small states in the inflammable dungeon that is the Middle East also offer lessons in cultivating relevance. Qatar and Oman. Doha and Muscat painstakingly cultivate their relevance by keeping doors open with everyone, be it state or non-state actors. This has made them indispensable actors in crisis times. While Qataris prefer direct mediation, Omanis like indirect facilitation.

Be it US negotiations with the Taliban, the Russia-Ukraine grain deal or the ongoing efforts to reach a ceasefire in Gaza, Qatar’s dainty imprint is conspicuously visible. As one analyst puts it, “only Qatar can talk with Sunni extremists and the Ayatollahs, as well as the Saudis, Turks, Israel and the United States.” Similarly, Muscat’s usefulness lies in facilitating back-channel talks between the United States and Iran, between the various warring sides in Yemen, and setting up talks between the Saudis and Iran. Even the now-defunct nuclear deal between the Security Council permanent members, Germany, the European Union and Iran was a fruit of Omani facilitation.

Put simply, national security is enhanced when states make themselves critical to the major powers.