Singaporeans will go to the polls on 10 July, after a characteristically speedy campaigning period of nine days, along with a “cooling-off day” on which electioneering is banned.

Unlike most elections elsewhere, a general election in Singapore isn’t about choosing between different political parties vying to form the government. Instead, it’s a question of how complete the dominance over parliament the People’s Action Party (PAP) – in power since 1959 – will have.

The PAP is asking Singaporeans for a “strong mandate” to lead the country into the post-pandemic world. Opposition parties, on the other hand, are urging the electorate not to hand the ruling party a “blank cheque” and to vote in opposition members who can speak up and hold the PAP to account.

In deciding between these sales pitches, Singaporeans will also have to navigate the quirks of Singapore’s electoral and political system.

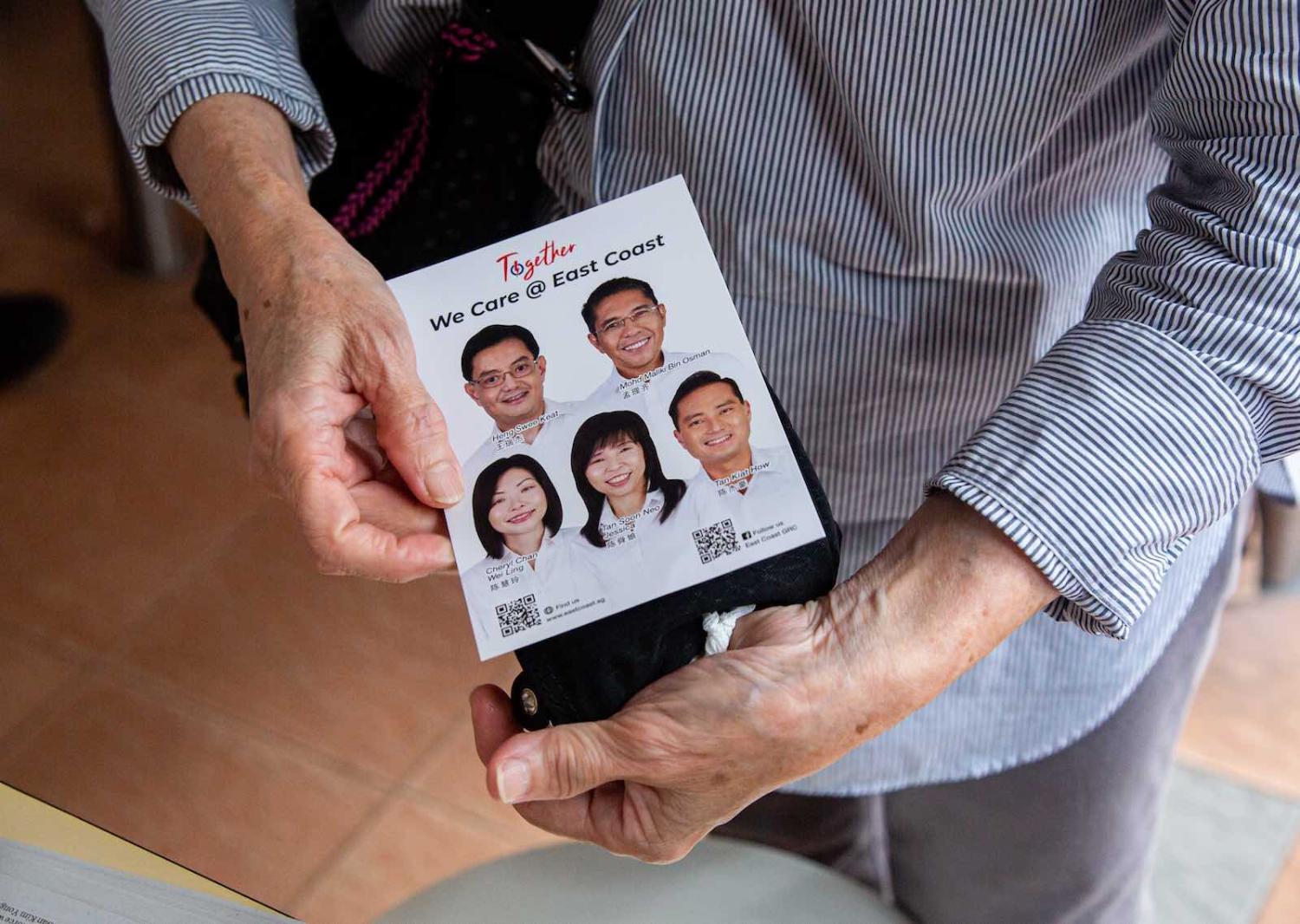

One unique feature is the Group Representation Constituency (GRC) system, introduced in 1988. Electoral divisions were put together to form mega-constituencies, contested by candidates who ran as a team. Singaporeans then cast their vote for the whole team, rather than individual politicians. Originally justified as a move to ensure minority representation in the House, GRC teams are required to have at least one minority candidate, certified by a committee to assess whether one is to be considered a Malay candidate, an Indian candidate, or a representative of a minority group that falls under the amorphous “others” category.

While the PAP might now characterise the NCMP scheme as affording Singaporeans a plurality of voices in parliament, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s stated motives were far more self-serving.

While the principle of minority representation is uncontroversial, it has been pointed out that the GRC system has given the incumbent PAP the upper hand. The party has a practice of spreading out its more senior and popular politicians and deploying them to lead GRC teams across the island. Voters are then left with the dilemma of either voting for the PAP or facing the prospect of losing an experienced cabinet minister. In such a way, the PAP has been able to “parachute” new and untested candidates into parliament, even into cabinet.

But the GRC system is also beginning to demonstrate that it’s a double-edged sword. In 2011, the Workers’ Party became the first opposition to wrest a GRC from the ruling party, kicking out two cabinet ministers in the process.

Even before the election campaign period officially kicked off this year, the pitfalls of the GRC system became apparent again.

Shortly after his introduction, PAP candidate Ivan Lim was called out on Facebook by a person who had served in his military unit, claiming that Lim had been arrogant and condescending. This was followed by further social media testimonies by others from Lim’s student days and his position as general manager of a shipyard.

These accounts, from people using their real names on social media, stoked an online firestorm. Comments about Lim ended up overshadowing the party’s own manifesto launch. An online petition attracted thousands of signatures in a matter of days, ending up with more than 20,000 signatories when Lim was dropped from the PAP slate.

If Lim had been running in a single-member constituency, people might have been willing to bide their time and vote him out at the polls. But Lim was to be fielded as part of a team helmed by the popular and widely respected senior minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam. If allowed to make it to Nomination Day, Lim would have been a shoo-in to parliament, despite all the negative accounts of his character.

The petition, then, was the only way Singaporeans could make their voices heard without also losing Tharman. It was a democratic exercise that needed to take place outside the electoral process to deliver the desired result.

As the PAP seeks the largest seal of approval they can get, party members have also argued that there’s no need for Singaporeans to elect any opposition members at all. If people are looking for alternative voices, the PAP argues, there will always be Non-Constituency Members of Parliament (NCMPs).

The NCMP scheme was introduced in 1984, three years after the PAP’s complete hold of parliament was broken by the Workers’ Party in a 1981 by-election. The idea behind the scheme is to set a quota for non-PAP members in the House: if fewer than the stipulated number of opposition candidates are elected, opposition candidates with the closest margins can enter parliament as NCMPs. Following constitutional amendments in 2016, the next parliament will require at least 12 non-PAP members.

While the PAP might now characterise this scheme as affording Singaporeans a plurality of voices in parliament, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s stated motives were far more self-serving. Allowing NCMPs into parliament, Lee said, would provide younger PAP MPs the opportunity to practise and sharpen their debating skills, while also protecting against accusations of cover-ups of alleged wrongdoings, by giving them vent through an apparent opposition. Another rationale was that the scheme would show Singaporeans that the need for official opposition was a myth, and that there was a limit to what the opposition can do.

Opposition parties have thus been hard at work to rebut this argument. As the only party to have had a toehold in the last parliament, the Workers’ Party has been particularly focused on this point. NCMPs, they point out, represent no constituency, and therefore have limited access to resources and a physical base from which they can continue to organise and build grassroots support. As unelected members, NCMPs can also be more easily dismissed as not having received a mandate from Singaporeans.

For the public, these elements all add up to a tricky exercise in tactical voting. It’s much less about weighing the merits of opposing candidates than about deciding on trade-offs between teams and trying to guess how everyone else will be choosing. And with the publication of opinion polls banned during the campaign period, Singaporeans are left second-guessing one another, blindly.