The informal grouping of Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, Turkey, Australia, known as MIKTA, was once called a new dynamic in diplomacy – a new form of middle power activism and the newest acronym in global governance.

But at five years old, it’s less dynamic and less active, and no longer the newest acronym. Indeed, its only success may be that it still exists.

With limited resources and a highly ambitious foreign policy agenda, South Korea must choose carefully where it commits resources.

A middle power diplomatic initiative is best defined as a structured diplomatic measure or strategy to respond to, or more characteristically, to alter anticipated disturbances in the external policy environment. They routinely involve a degree of innovation (new partners, structures, approaches), focus, and maximise the use of limited resources. Such initiatives seek partnerships with, and support from, like-minded states and are presented as contributing to the global good.

Characteristically, there is a clear link between aim and initiative. This can be seen between agricultural trade liberalisation and the formation of the Cairns Group. Other examples include open (non-exclusive) regionalism and the formation of APEC, or the prevention of genocide and the establishment of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty. Yet it is here that MIKTA fails.

The 2015 “MIKTA Vision Statement”, and 2017 “Guidelines on the Works and Activities of MIKTA”, use all the keywords – “agenda-setter”, “facilitator”, “cross-regional consultative platform”, and “global governance reform”. The website highlights its activities – electronic commerce, migration and refugees, gas security, terrorism, natural disasters, nuclear issues, as well as parliamentarian, journalist, and academic conferences. What it doesn’t highlight is a clear link between aim and initiative.

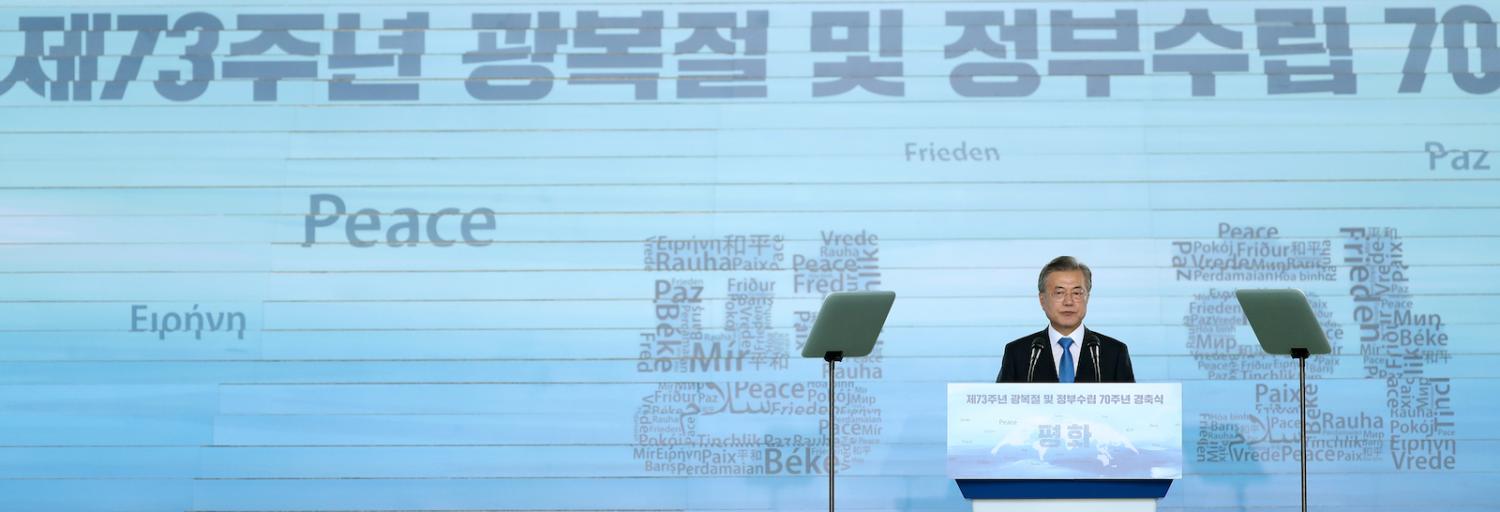

For South Korea, MIKTA is now a challenge for the Moon Jae-in administration. Seoul will again lead in the grouping in two years time. With limited resources and a highly ambitious foreign policy agenda, South Korea must choose carefully where it commits resources.

Moon’s administration has three broad foreign policy aims, which distinguish it from its predecessors. First, it seeks support for reconciliation with North Korea. Second, it seeks to diversify diplomatic interaction and move away from a reliance on the US and China. Third, it seeks to promote “people’s diplomacy”, carrying on the “candlelight revolution” that brought it to power by better reflecting public sentiment in foreign policy.

MIKTA does not immediately present itself as an ideal diplomatic tool to support any of these aims. The Moon administration has two options.

The first option is to fit square pegs into round holes. It could squeeze out yet another weak MIKTA declaration on peace and North Korea, bring MIKTA to the diplomatic diversification carnival with an ASEAN-MIKTA or India-MIKTA talk-fest, or wholeheartedly re-label each and every minor MIKTA outreach initiative as people’s diplomacy. This option would discredit the Moon administration’s foreign policy and further discredit MIKTA.

The second option is to double down on MIKTA, using the weak link between aim and initiative to transform, strengthen, and actually use MIKTA. The Moon administration could turn to MIKTA as an engine to drive its three broad foreign policy aims of reconciliation with North Korea, diversification of diplomacy, and reflection of public sentiment in foreign policy.

Defining the Korean peninsula as a global governance issue, involving nuclear proliferation, conflict risk, and division, justifies a middle power role, in which each MIKTA state has historical, political, economic, and/or security interests. MIKTA could potentially serve as an avenue for a more creative middle power approach to Korean peninsula affairs – an approach which goes beyond the limits of crisis diplomacy and leadership summits.

MIKTA could lead an international commission reporting on the long-term challenges to Korean peninsula reconciliation. MIKTA could establish a “council of elders” to investigate middle power roles in what has traditionally been seen as a major power concern. MIKTA could establish an oversight committee to provide accountability and transparency in disarmament/incentive processes. An array of creative, innovative options to actually use MIKTA do exist.

Working closely with MIKTA would diversify South Korea’s diplomacy, and give it a stronger voice in negotiations with both the US and China. Coalition building increases a middle power’s negotiating leverage, adds access to important networks and resources, and tempers overly ambitious goals. Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey, and Australia are ideal partners, and through their reach would substantially enhance South Korea’s capacity.

Additionally, working through a MIKTA body would better reflect public sentiment in foreign policy by increasing transparency and accountability. MIKTA allows interaction at multiple levels, including officials, academics, journalists, non-governmental organisations, and students. Importantly, it would also increase the likelihood that initiatives would continue after the Moon administration. Embodying progress in a multilateral or regional body encourages subsequent administrations to sustain initiatives to avoid impacting the state’s reputation as a reliable partner.

Whether the Moon administration seeks to fit square pegs into round holes, or chooses to double down, the next few years will be critical for MIKTA. At five years old, from next year each state will be leading the grouping for a second time. With South Korea to lead in 2020, it’s time for the Moon administration to think more creatively about MIKTA and the Korean peninsula.