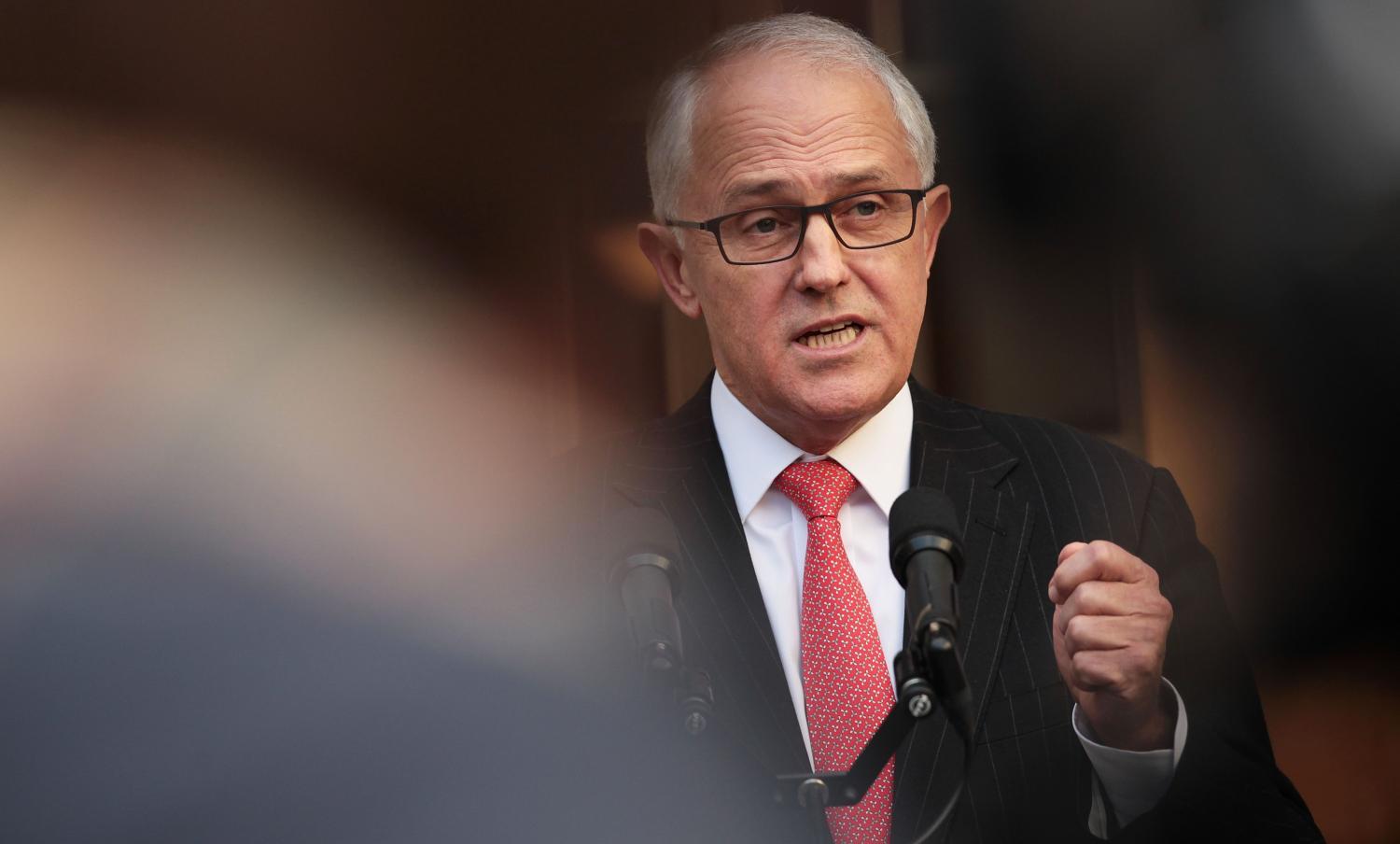

More than 30 years after he gained international prominence for inflicting humiliating defeat on Margaret Thatcher's British government in the Spycatcher case, espionage is back on Prime Minister Turnbull's agenda, but in an utterly different form.

Sometime towards the middle of this year, the report of the Independent Intelligence Review will lob on Turnbull's desk. It will be the first time since his acclaimed victory over Thatcher and the British intelligence establishment in 1986 that Turnbull will have had to give his full attention to the complex issues of balancing the imperatives of secret intelligence gathering and security and defending liberty and freedom.

The report will be a heavyweight document. The make-up of the review panel – former Howard government adviser Michael L'Estrange and intelligence community heavyweight Stephen Merchant, plus British intelligence expert Sir Iain Lobban as a consultant – guarantees a comprehensive and insightful assessment of the state of Australia's intelligence agencies.

The review has much to grapple with. The national and international security environments are facing major changes and challenges. Domestic security agencies are being tested by a heightened risk from domestic terrorism while also dealing with increased demands for national border protection. Cyber-threats from foreign powers are emerging as a serious security concern. Increasingly unpredictable regional and global security issues pose big tests for the capabilities and the judgment of the intelligence community and for policymakers. These changes demand a new and piercing look at the current state of Australia's security and intelligence agencies. What is the right structure and allocation of resources for the major agencies? Should there be changes to the powers and responsibilities of the agencies? And who should run them? These are key decisions that the government will have to take, based on the review's advice.

For Turnbull, who three decades ago personally inflicted a brutal lesson on the British intelligence establishment by using legal argument to expose its over-zealous secrecy, arrogance and duplicity, the task now will be to address the challenges of national security from the other side of the fence.

The security of the nation is Turnbull's first responsibility as Prime Minister, but one for which some with long memories question Turnbull's credentials. Right wing activists and arch-conservatives have warned that Turnbull's historic libertarian and 'leftist' instincts may bias him against the intelligence agencies and their work. Blogs can be found on the internet branding Turnbull's custody of the security apparatus as dangerous.

Such material is dismissed inside the Turnbull government as 'raving nonsense'. A senior Cabinet minister told The Interpreter that the idea that Turnbull might have an innate 'anti-intelligence establishment bias' was absurd.

'Malcolm takes his responsibilities to protect the security of Australia extremely seriously,' the minister said. 'He has approached the intelligence review absolutely focused on the need to ensure that we have the best people and structures we can have in place to protect the Australian people.'

Another insider said: 'Just because Malcolm didn't announce the review surrounded by Australian flags and people in uniform doesn't mean he is downgrading the issue of national security. On the contrary, he sees it as far more serious than an opportunity for putting on a show to score political points.'

In the intervening years between the Spycatcher case and his prime ministership, Turnbull made only limited forays into national security debates. His most significant contribution was a speech in March 2011, when he was shadow communications minister, titled 'Reflections on Wiki-leaks, Spycatcher and Freedom of the Press'. The speech can no longer be found on Turnbull's website, but an archived version can be read here.

At the time it was made, the media focused on Turnbull's strong criticism of then Prime Minister Julia Gillard's support for US attacks on Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, whom some US politicians had suggested should be assassinated for the publication of vast amounts of secret State Department documents. Turnbull argued that Gillard should have registered 'profound unhappiness' at such threats.

But the more significant parts of the speech were Turnbull's nuanced views about the Wikileaks saga. Unlike many conservatives, Turnbull did not see the leaks as breaches of the law, nor did he see Assange as a criminal. He argued that there was a right to publish, provided the publication did not compromise current intelligence operations, nor result in risks to people in diplomatically or politically sensitive positions. He accused those authorities and individuals demanding punishment for Assange of exaggerating his importance and giving him unjustified notoriety, in the same way that he believed the British government had done with Peter Wright, the rogue MI5 agent who wrote Spycatcher.

Turnbull's views then were consistent with his long-standing (small-l) liberal ideals. Will he bring similar thinking to his consideration of national security issues now and, if so, what might this mean for the Independent Intelligence Review?

Government insiders say that Turnbull will be entirely guided by the advice of the review panel. 'He has very high regard for Michael L'Estrange and Stephen Merchant,' a senior government official said. 'When their names were proposed for the panel, he had no hesitation in appointing them. We expect them to deliver a thoroughly professional, balanced and sensible report. We don't expect this to lead to any upheaval or dramatic change.'

Some fear this will mean disappointment for those who believe there is a case for significantly rethinking Australia's security and intelligence priorities.

Hugh White, Professor of Strategic Studies at the Australian National University (and a regular contributor to the Interpreter), said that the most important question was to determine whether, as a result of the recent intensified focus of national security on border security and the threat of domestic terrorism, too little attention was being given to regional and international security issues.

White is concerned that the Turnbull government has become complacent about the potential risks for Australia from heightened rivalry between China and the US in the Asia-Pacific region, which he says is likely to see increased tensions in the Trump presidency.

But White does not believe Turnbull has any inclination to move beyond the positions of the previous Abbott and Gillard governments, which both assumed continuing US supremacy in the region for the foreseeable future.

Political insiders agree. They say that Turnbull has far too many domestic problems on his plate to use political capital to make changes in national security – not currently an area of partisan political argument.