Labour’s first month in office should reassure those wanting to see a United Kingdom remaining engaged in the Indo-Pacific – particularly in Australia given the future submarine ambitions via AUKUS. The change at 10 Downing St has already shown clear points of difference to the previous Conservative approach to foreign policy, but the overarching strategic, economic and normative rationale remains the same.

Europe is going to be the focus under Labour, something it was explicit in stating in the lead-up to the election. New prime minister Keir Starmer wants a “reset” with the European Union mainly regarding the economic relationship, but also in the strategic realm by seeking to form “an ambitious new UK-EU security pact to strengthen co-operation on the threats we face”. NATO will be Labour’s anchor in the Euro-Atlantic, and Starmer has already been personally active in engaging the alliance as well as the nascent European Political Community.

From the warm pint-sharing embrace of David Cameron to the frothing containment-promoting of Liz Truss, the previous government had settled on a confusing policy that attempted to please “hawks” and “doves” alike in Westminster.

Labour has also rightly sought to distinguish its policy towards China from that of the Conservatives. From the warm pint-sharing embrace of David Cameron to the frothing containment-promoting of Liz Truss, the previous government had settled on a confusing policy that attempted to please “hawks” and “doves” alike in Westminster by continuing to engage China economically, all while clunkily labelling the country an “epoch-defining challenge” under Rishi Sunak.

Labour has promised to “co-operate where we can, compete where we need to, and challenge where we must” with China in their manifesto, a position re-iterated by Catherine West after she was confirmed last week as UK minister for the Indo-Pacific. The mantra is similar to Australian Labor’s of “we will cooperate where we can, disagree where we must, but engage in our national interest”. Copyright questions aside, this demonstrates that UK Labour, like Labor when it came into power in Australia, sees no benefit in rhetorical flourishes and applying labels when dealing with China.

This is a good start, but China policy under Labour still needs fleshing out. Filling the gaps of these “three Cs” will not be straightforward.

China is Britain’s sixth-largest trading partner and largest in Asia, and there were nearly 100,000 first-year enrolments by Chinese nationals in British universities in 2021-22, the largest country group. How to detach trade from geopolitics is a challenge every country faces with China.

Hong Kong is also a sticking point. The fate of the territory carries emotional weight, due to feelings of betrayal in the United Kingdom about the crackdown on rights by Beijing, and resentment by China regarding British efforts in welcoming fleeing Hong Kongers. The promised “full audit” of the relationship will hopefully lead to some clarity.

The next step for Labour’s Indo-Pacific policy will be discerning how to continue expanding defence relationships in the region.

New trade minister Douglas Alexander has promised to drop “post-imperial delusions” that he claimed had driven Britain’s post-Brexit global economic engagement, particularly in the Indo-Pacific. The Australia-UK trade deal struck in 2021 has been widely criticised as being one-sided in Australia’s interests. While such assessments may be true, that deal manifested from the political and symbolic imperatives of the Conservative government after the split with the European Union – that is, a desire to demonstrate “Global Britain” in action rather than delusions of empire. It also downplays Britain’s accession last year to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans Pacific Partnership. Regardless, Alexander’s comments show that interests, and interests alone, will now seemingly drive the UK’s trade policy.

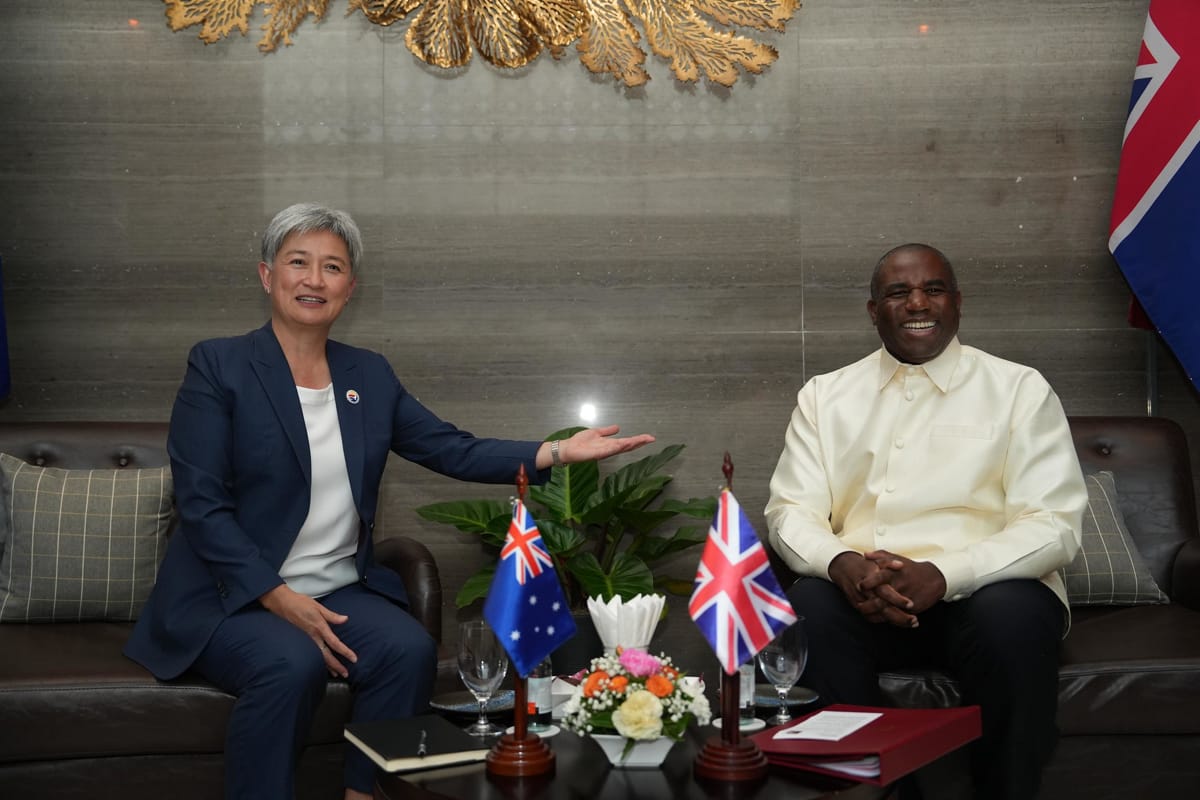

Those interests still see Britain firmly engaged in the Indo-Pacific. Indeed, Alexander has been explicit in his desire for a strong trade deal with India, and foreign secretary David Lammy’s visit to India and attendance at the ASEAN foreign ministers meeting were centred on furthering economic ties, as well as environmental stewardship.

So far, all of this is relatively similar to the Conservative approach laid out in the Integrated Review policy paper and its 2023 “Refresh". That approach was predicated on fostering stronger relationships with allies and partners old and new. Labour seems to be doing just that, as well as acknowledging the importance that environmental stewardship and diplomacy play in the region.

The next step for Labour’s Indo-Pacific policy will be discerning how to continue expanding defence relationships in the region. The fate of the two offshore patrol vessels, HMS Spey and HMS Tamar, for example, is unclear. Should they continue operations as normal? Be replaced by frigates, as some have suggested? Or be withdrawn entirely? Lofty language around “progressive realism” and the promotion of “progressive values” will only go so far.