The new Biden administration in Washington is reviewing its North Korea policy, a process that is expected to be completed next month. Pressure from experts is mounting for the administration to restart diplomacy with North Korea with more pragmatic goals, such as a shift away from complete denuclearisation in the near term to an aim of arms control.

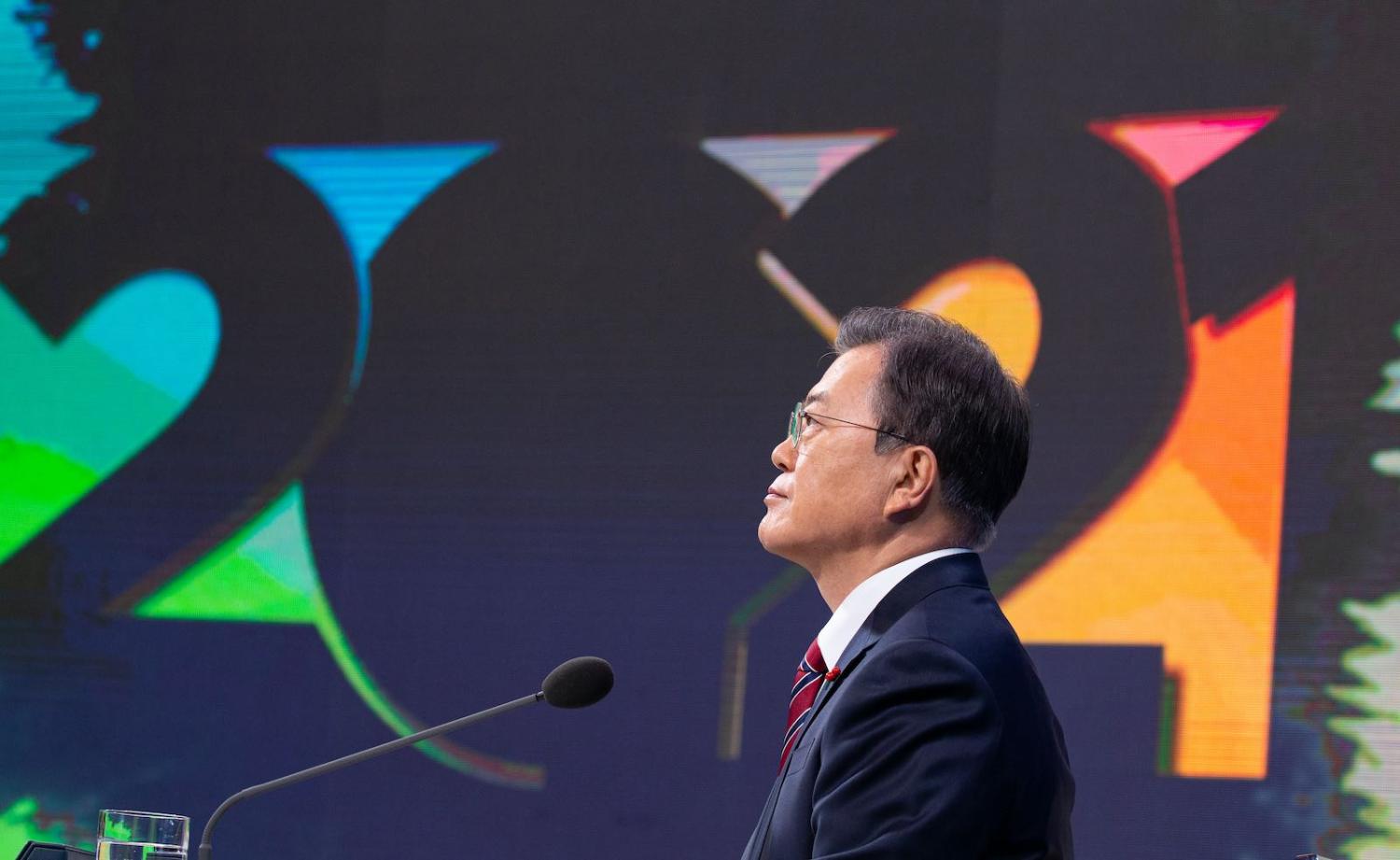

South Korea is also pushing hard for a resumption of US–North Korea talks. South Korean President Moon Jae-in hoped that the upcoming Tokyo Olympics would offer the opportunity for dialogue between Pyongyang and Washington. Washington seemed to heed the urging and has sought to contact Pyongyang via various channels since mid-February to prevent tension from escalating. But North Korea does not appear to have responded to the US outreach.

There is hope that Biden may yet engage. In his essay on US–South Korea relations published on Yonhap News days before the 2020 election, Biden promised to engage in “principled diplomacy and keep pressing toward a denuclearised North Korea and a unified Korean Peninsula”. Marc Knapper, US deputy assistant secretary of state for Korea and Japan, affirmed in a recent teleconference with his South Korean counterpart that both countries were on the same page on North Korea denuclearisation and Washington wanted to hear South Korea’s opinions when crafting its policy review. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin will visit Seoul this week to discuss North Korea review and other regional issues with their Korean counterparts.

But a mismatch in focus on the key issues means that the coordination efforts between the two nations can still go wrong. The US wants to fix the alliance to get South Korea on board with the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), which held its first leaders level meeting at the weekend. South Korea wants to fix the alliance – to ensure US support for its North Korea diplomacy.

From the US perspective, revitalising a US–South Korea alliance shaken by the Donald Trump presidency is the most important task. Less than two months after Biden’s term commenced, Washington and Seoul reached a new cost-sharing agreement for the US troops based in the country. Seoul would pay 13.9% more from 2019 to 2025 (Trump had demanded a 400% increase).

Biden also sought to leverage the US influence to fix Japan–South Korea relations, which have been declining since 2018. Such repair is important to coordinating North Korea policy among the three allies and to paving the way for Seoul to join an expanded Quad (a “Quad Plus”) by bringing the Korea issue to this dialogue. The intention is clear when the Quad leaders during their first meeting mentioned the denuclearisation of North Korea as one of the key issues the Quad would focus on. Biden’s broader motive appears simple: to enlist South Korea’s help against China.

However, from the South Korean perspective, revitalising the alliance with the US is welcome, but its focus should not be to construct an anti-China alliance. The Moon administration desires a strong alliance with Washington to bolster its North Korea policy – that is, if dialogue fails, the US will commit to South Korea’s defence against North Korea’s provocations; if dialogue succeeds, Washington should support Seoul’s outreach to the North by relaxing its sanctions or toning down joint military exercises.

South Korea’s motive is not to balance against China. Instead, Seoul desires great-power cooperation in the Pacific to gather momentum for peace talks with Pyongyang.

In other words, South Korea’s motive is not to balance against China. Instead, Seoul desires great-power cooperation in the Pacific to gather momentum for peace talks with Pyongyang.

It is at this point that the two allies may end up at cross purposes. Biden’s efforts to nudge South Korea towards the Quad can undermine Moon’s push for a peace treaty with North Korea. Even if there is a commitment to coordination from both sides, US–South Korea coordination was not equal in the past, and there is no guarantee that it will be equal in the future. The US has often been able to dictate the pace of inter-Korean rapprochement, to South Korea’s dismay, by the control of international sanctions. If Biden prefers to maintain a “sanctions-first” approach, it is hard to imagine him lifting those sanctions based on Moon’s requests – and the US is already hesitant to reward North Korea after its recent nuclear development activities.

Another way coordination can go wrong is Biden trying to integrate South Korea’s desire for diplomacy with the North into his vision of a Quad Plus. Unfortunately, an addition of more veto players often leads to deadlock rather than progress.

For example, Biden’s efforts to coordinate North Korea policy with Japan and South Korea may frustrate Moon’s détente. In the section of the Quad leaders’ joint statement relating to North Korea, they put an emphasis on the “immediate resolution of the issue of Japanese abductees”, an issue long known to be a killer of Japan–North Korea talks. The leaders did not discuss a peace treaty between North and South.

Moon would not want to wait for the abduction issue to be solved before restarting diplomacy with Pyongyang, and he would not appreciate Japan or any other country holding a veto over South Korea’s policy towards the North. Moreover, it is contradictory to put South Korea’s North Korea policy into the Quad vision, because the former needs China’s help, while the latter is directed against China.

Seoul knows that a hardening of the US-China rivalry would only reinforce the North-South geopolitical divide, and it wants to distance itself from an anti-China alliance. It also knows that a strong US–South Korea alliance should be a vehicle towards better inter-Korean relations, rather than a cause of negotiations breakdown. Washington should heed these concerns, or else it will be left to wonder why the effort to revitalise the alliance hurts rather than improves US–South Korea relations.