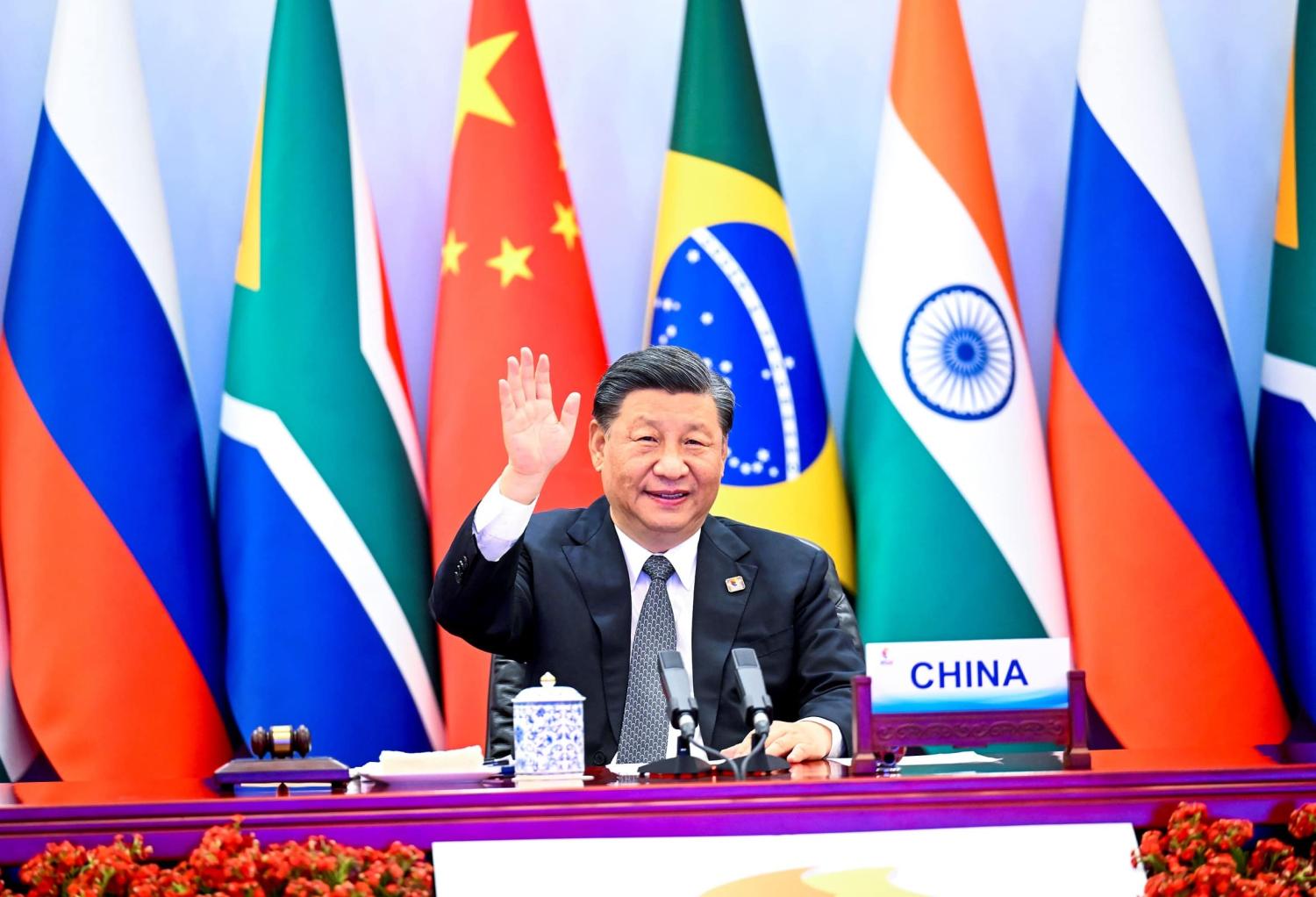

Overshadowed somewhat by the ongoing attention on China’s development efforts in the Pacific, last month China’s President Xi Jinping hosted a virtual High-Level Dialogue on Global Development on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit. The dialogue was noteworthy not only because of its lengthy list of 32 deliverables – some which have significant ramifications outside of the development sphere – but because it officially reframed China’s development efforts under the banner of its new “Global Development Initiative”.

Xi first introduced the GDI in a virtual address to the UN General Assembly in September last year as a way to support economic and social development around the world in response to setbacks caused by Covid-19. The GDI, according to Xi, would be a new effort to help accelerate momentum on the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and “steer global development toward a new stage of balanced, coordinated and inclusive growth”. Priority areas for the GDI would include “poverty alleviation, food security, Covid-19 and vaccines, financing for development, climate change and green development, industrialisation, digital economy, and connectivity”.

China’s proposal of the GDI is certainly timely. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to huge development setbacks around the world, erasing decades of progress.

Despite the ambiguity on what the GDI will actually entail, more than 100 countries and international organisations have since expressed their support for the initiative, while 50 countries have joined the UN Group of Friends of the Global Development Initiative set up by China in January. The GDI has been welcomed by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres and various UN agencies, while references to the GDI have been increasingly cropping up in joint statements between China and other countries.

China’s proposal of the GDI is certainly timely. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to huge development setbacks around the world, erasing decades of progress. According to the World Bank and the World Health Organisation, the number of people living in extreme poverty around the world rose in 2020 for the first time in 20 years. This comes amid concerns the global economy is heading into an era of stagflation and downturn that will make reversing these trends all the more challenging. There certainly needs to be significantly more momentum across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals if they have any chance of being achieved by 2030 – indeed, even with more momentum, there’s a very real risk they won’t be met, like the Millennium Development Goals before them.

Any efforts to eradicate extreme poverty and advance sustainable development should be a positive for the global development agenda. China’s GDI, however, also represents a number of efforts to reshape broader global rules and governance in line with Beijing’s interests. This raises a number of red flags that will need close watching as the initiative unfolds.

For example, the GDI includes some ambiguous but problematic language that has significant implications for human rights around the world. The GDI frames “development” as the “master key” to “all problems” and positions development as a prerequisite to the enjoyment of human rights. If this sounds familiar, it’s because China has long insisted on the right to prioritise economic development before respecting and upholding other human rights. This approach is problematic because it directly counters the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It suggests human rights are voluntary, rather than an international legal obligation, and erodes the existing international human rights regime by creating written precedent for states not to respect or uphold human rights until they have reached a deliberately vague (and conveniently elusive, in China’s case) definition of “developed”.

Xi’s link between the GDI and China’s new Global Security Initiative is concerning, inextricably tying development efforts with Beijing’s security interests.

Concerningly, the GDI also uses lots of language around the “collective” and “the greater good”. Again, the focus on “collective” rights will sound familiar as a common refrain of the authoritarian. China has long insisted on the concept of the collective rights of the state over the rights of the individual in pursuit of “the greater good”. This poses a direct counterpoint to the concept of universal and inalienable human rights, and helps advance China’s broader efforts to create an alternate human rights framework that preferences the nation state over the individual and weakens human rights for all.

Lexicon and emphasis might seem minor, but this language matters – it particularly matters in the international system where, over time, it has the capacity to create or degrade international law and norms and set precedent for other international agreements and treaties.

Language aside, other red flags are evident. Xi’s link between the GDI and China’s new Global Security Initiative is concerning, inextricably tying development efforts with Beijing’s security interests. Despite all the GDI’s references to the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, it’s also unclear how the GDI actually advances the existing SDGs. There’s also the risk that the GDI will cherry pick which aspects of the SDGs it advances in line with Beijing’s interests, to the detriment of the established and international agreed principles of the global development agenda. The GDI also brings in a focus on connectivity and data, which will have implications for these issues in broader global discussions.

It is still early days for the GDI. But beyond its focus on “development”, it appears clear that the GDI is China’s latest attempt to reshape broader global rules and governance in its favour, with significant implications for human rights. The GDI has so far received little public attention in the West or among the development community. A close watch is warranted as China’s latest idea unfolds.