On Monday The Australian published an article titled “Pacific nations drowning in Chinese debt”. It suggests that a large number of recent “white elephant” projects are becoming an unsustainable burden on Pacific Islands countries.

Although this contains a kernel of truth, it’s not accurate to suggest that these nations’ problem is that they are “drowning in debt”.

In Vanuatu, at least, the issue is not overall debt load – not yet, anyway. The latest IMF debt assessment rates Vanuatu’s risk of default as “moderate”. Relative to other developing nations, its debt to GDP ratio is manageable.

Vanuatu’s immediate problem is cash flow. In 2012 a single sentence was changed in a key piece of legislation, with the result that new loans no longer required parliamentary approval. Projects could now be signed off at the ministerial level. Within months, new projects, and new loans, were being announced at an alarming rate.

Within a couple of years, Vanuatu had added hundreds of millions of dollars to the liability column. Happily, an Australian-funded governance program, coupled with a domestic commitment to avoid deficit spending, had built a financial regime that kept the government living well within its means. Vanuatu’s debt in 2013 was modest at just over 20% of GDP.

By 2020, however, Vanuatu’s debt service payments will have risen significantly. The nation now has to manage an impending cash flow crunch. The Department of Finance and Treasury has staffed a debt management unit and given it a place at the policy table. In late 2017, the Council of Ministers approved a rise in the Value Added Tax (VAT) rate from 12.5% to 15%, effective 1 January 2018.

VAT revenues should rise by approximately 20% above their normal growth rate by 2020. In addition, Vanuatu’s controversial passport sales programs have become its largest source of non-tax revenue, adding tens of millions of dollars annually to general revenues. Driven by this unanticipated windfall, revenues have run well ahead of expectations for past three years.

Debt is not the problem some people make it out to be. But that’s cold comfort when we look at the overall development picture.

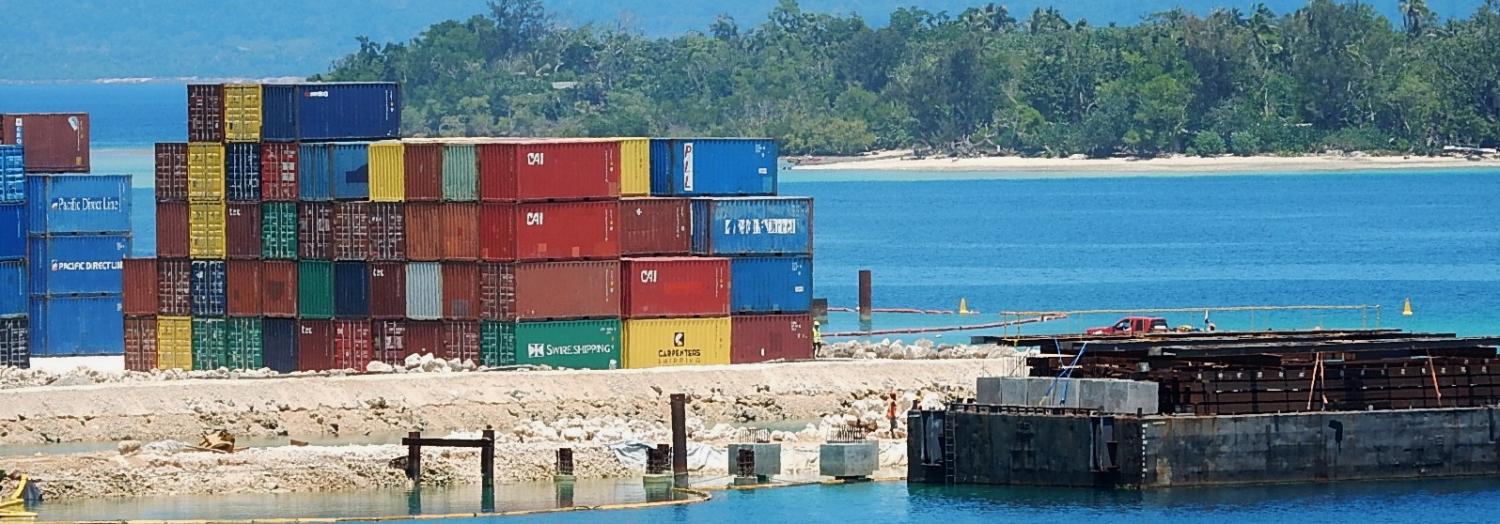

The country has embarked on an ambitious gambit, using infrastructure investment to catalyse a transformation of the national economy. In the past few years, Vanuatu has either started or completed the construction of two large-scale wharf facilities and about half a dozen smaller ones; two major roads; the rehabilitation of another 100-plus kilometres of cyclone-damaged roadway; major repairs and upgrades to three airports; a new conference centre; a sports facility that recently hosted the 2017 Pacific Mini Games; the complete rehabilitation of its flagship secondary school; and an urban development project that has literally transformed the capital.

These are only the headlines. There are also private sector–driven plans to construct a brand new international air terminal, a new 400-room resort, and a massive new subdivision outside the capital, dubbed the “Emerald City”, aimed at Chinese citizens seeking rest, relaxation, and residence in the tropics.

The government’s gambit is that growth will come soon enough to meet Vanuatu’s spiralling debt service commitments; however, that is not assured. A single cyclone could throw plans off balance.

Some loans the nation has taken on are extremely concessional in nature. For example, the US$70 million Japanese-funded Port Vila wharf project features a 0.55% interest rate, a 10-year grace period, and a 40-year repayment window.

In contrast, a similar wharf in the northern port of Luganville, funded by the China EXIM Bank and built by the Shanghai Construction Group, cost about $15 million more, features a 2% interest rate, a 5-year grace period, and a 20-year repayment window.

Worse, concerns over the kind of bollard installed on the Luganville wharf led cruise lines to cancel dozens of visits, creating millions of dollars in opportunity costs and knocking the northern town’s plans to become a tourism hub into a cocked hat.

Efforts are underway to mitigate the problem and allay safety concerns. Just this week, the Voyager of the Seas, a 300-metre-long cruise ship, was able to berth safely during a test visit.

An ANU study published by the Development Policy Centre shows that successful infrastructure investment depends more on the recipient country’s capacity than on the source of funds. Not all projects are created equal, and few countries have grounds to brag about their performance.

The tit-for-tat rhetoric coming from both China and Australia does the issue injustice. It is not only inaccurate but also, more importantly, denies the agency of Pacific Islands nations themselves. Without a voice in this discussion, these nations are certain to be saddled with more failed infrastructure projects in the future.