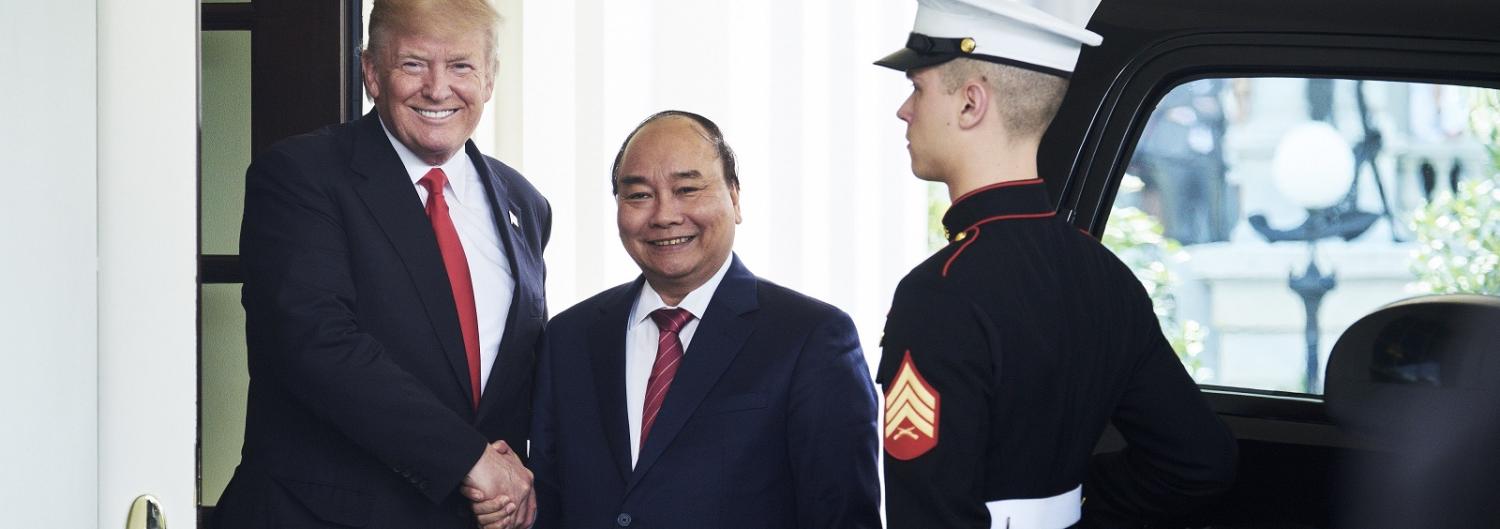

It was trade, not China's manoeuvring in the South China Sea, that was top of the agenda when Vietnam’s Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc met US President Donald Trump on Wednesday in the first visit by an ASEAN leader to Washington under the new administration. It was a slightly surreal affair with Phuc, leader of a communist state, on a mission to promote free trade to the leader of the US.

Vietnam doesn't figure in the list of America's top 15 trading partners but the US trade deficit with Vietnam is its sixth largest. To help address this, Vietnam placed some very large orders during Phuc's Washington tour, fulfilling a pledge he made in a Bloomberg interview just before the visit to 'import lots of meaningful, high value products.'

Altogether the US Commerce Department announced some 13 new deals with Vietnam worth over US$8 billion, including a $3.6 billion agreement for Vietjet Aviation to purchase 215 engines from a General Electric subsidiary to power the airline's fleet. Vietnam has been spending a lot lately to expand its aviation industry as its population grows. The GE deal follows a $6.5 billion deal with Airbus, cemented when then French President Francois Hollande went to Vietnam last year, and an $11.3 billion contract between Vietjet and Boeing.

The US President made all the right noises about new business from Vietnam. 'They just made a very large order in the United States and we appreciate that for many billions of dollars, which means jobs for the United States and great, great equipment for Vietnam,' said Trump. He did not say much else about the meeting, which was brief and marked the end of Phuc’s three-day Washington trip.

Since Trump's inauguration in January, Vietnam has wondered where its relationship with the US - an important part of Barack Obama's 'pivot' to Asia - is headed. On 1 April Trump sent a letter to President Tran Dai Quang in which the US President wrote that he hoped for better ties and engagement. However, to date the most significant event of the Trump presidency for Vietnam took place on 23 January, when Trump withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement. Vietnam was disappointed, not just because of the loss of new trade avenues promised by the TPP but because it was also banking on the agreement to assist in reforming its problematic and unprofitable state-owned enterprises.

While Vietnam shifted to a market economy back in 1986, its leadership has always approached economic reform with mixed views. Though keen to alleviate poverty, Vietnam's leaders have been sceptical of the wonders of capitalism, as promised by the West. However even the older, more traditional General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong said he was committed to further economic reforms after the last national congress. The TPP would have helped.

On the trade front, there is no doubt Vietnam has done well from the bilateral trade agreement it signed with the US in 2000, hence Phuc's efforts to make nice with a President who had campaigned on a protectionist platform that targeted nations that run a large trade surplus with the US. Vietnam's economy has performed strongly, with growth averaging 6.4% each year since 2000, but the rate of growth is now slower than it has been since 2014 and, with a large and growing deficit with China, Vietnam needs its exports to the US to continue.

And what of the South China Sea? Since Trump won the White House, Vietnam and other South China Sea claimants, along with regional actors including Japan and Korea, have wondered about the Administration’s plans for the region. Would the US focus on the region diminish and how would a pullback manifest itself? How would China react? Vietnam stayed quiet after the Philippines’ win in the Hague last year, to avoid antagonising China after it had been poked rather too hard. But in April, a fleet of Vietnamese fishing trawlers went to one of the contested areas in what the Lowy Institute's Euan Graham described as 'a third-party intervention (that) serves to keeps the Hague award alive'.

The recent freedom of navigation operation by the US Navy that came within 12 nautical miles of one of China’s artificial islands has gone some way to easing Vietnamese concerns regarding a scale-back of the US presence in the region. It was this concern, as well as worries over trade, that pushed Vietnam to lobby so hard for this week's meeting.

In Vietnam this week there was a nod to these concerns when the country took delivery of six military patrol boats produced by Louisiana’s Metal Shark. US Ambassador Ted Osius, there for the handover in central Quang Nam province, said: 'Vietnam’s future prosperity depends upon a stable and peaceful maritime environment.'

However, strategic issues didn't appear to rate highly in the Phuc-Trump meeting, a contrast to previous trips to the US by Vietnamese leaders, such as the 2015 visit by General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, that had a far stronger strategic cast.

A US that is less engaged in Asia generally and Vietnam in particular does have some upside for those who make the trek to the US capital. The Trump Administration is not one to dwell on human rights issues, so is less inclined to either lecture, press for improvement by linking other matters to improved human rights, or call for greater press freedom. All of these were hallmarks of the Obama Administration.

So while Prime Minister Phuc may not have gained much insight into the US strategic focus in Asia post the pivot, on balance his visit was a success, with Vietnam reassured its trade with the US will continue uninterrupted.