Prime Minister Scott Morrison has copped flak for claiming that Australia regarded the Pacific countries as vuvale (a Fijian term for family). He was under fire again following the Pacific Island leaders meeting in Tuvalu last month, for emphasising Australia’s aid contributions to the region and managing to water down the final communique on climate change.

The strong and genuine “family” ties developing between Australia and the Pacific Islands are extremely unlikely to ever develop between the Pacific countries and China.

Fiji’s Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama alleged that Morrison was “heavy handed, paternalistic, and insulting” during the meeting, and no doubt in an effort to needle the regular lament among Australian politicians or the media that Australia has been replaced by China in the Pacific, Bainimarama said Beijing would never publicly point out to Pacific Island leaders how much aid they were giving. Bainimarama’s comments were also seized upon by China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang, who declared China did not attach any political strings to its aid to the Pacific countries.

But regardless of insensitive statements from the Australian government or the canny responses from some Pacific Island leaders hoping to play “the China card” with Australia, one should not lose sight of the strong and genuine “family” ties developing between Australia and the Pacific Islands, ties that are extremely unlikely to ever develop between the Pacific countries and China.

The Australian government needs to strengthen these “people-to-people” links further instead of competing with Chinese aid, which is an exercise in futility.

Pacific kith and kin: the ABS data

Deep “kith and kin” relationships are developing between large numbers of Australian residents who are originally from the Pacific and their Pacific homelands. According to the most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics data, while Australian residents born in Australia increased by a mere 26% between 1996 and 2018, those with country of birth as:

- Fiji increased by 86% (to 75,930);

- Samoa increased by a massive 197% to 31,610;

- Tonga increased by 63% to 12,650.

These numbers may seem small compared to the far greater numbers of Australian residents born in China (650,000) or India (592,000). But add to them also the numbers in their families born subsequently in Australia and you have “Pacific Island populations” in Australia, who are a very large proportion of their Pacific home populations, and even higher if you add their counterparts in New Zealand.

Those in Australia (and NZ) equal about 50% of the current population of Fiji, and more than 100% of those of Samoa, Tonga, and the Cook Islands.

These Pacific Islanders in Australia not only travel back and forth, but they send home large remittances, which are a very large part of the export earnings for their home nations and far greater in value than the dollar value of Australian development aid to the Pacific.

The ABS data also indicates that annual emigration from these Pacific countries is continuing at the same high rates as between 1996 and 2018.

Regardless of aggravation and posturing by some Pacific Island political leaders, the ordinary people and especially the young and educated ones from Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, and the Cook Islands, know all too well which country has the greatest potential of supporting their future prosperity (incomes, education, and health), and especially that of their children. That country is not China, regardless of how many Chinese-built roads, sports stadiums, or parliament houses funded by Chinese aid or concessionary loans are plonked down in Pacific countries, allegedly “with no political strings attached”.

A better Australian climate change response

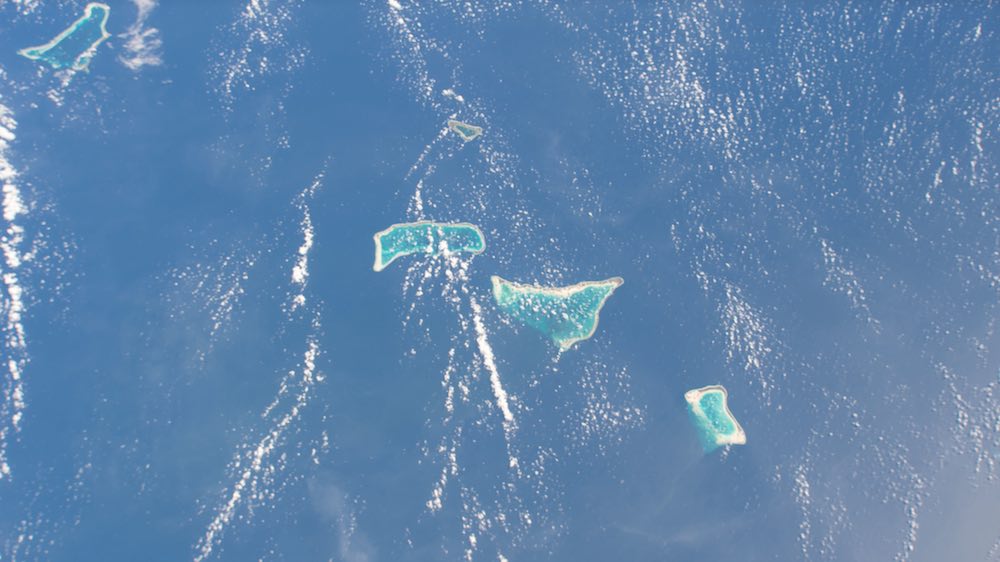

The world today knows that countries such as Tuvalu and Kiribati, with their land mass being barely two metres above the sea levels at high tide, will go under the ocean within three decades if climate change proceeds at the current rate.

Bainimarama grandly offered Tuvalu (population 10,000) and Kiribati (population 120,000) climate-change refuge in Fiji. Indeed, Tuvaluans have for decades been investing and living in Fiji, and Kiribati has already bought large properties in Fiji, with more land mass than in Kiribati itself.

But in 2018 there were only 200 Australian residents who had been born in Tuvalu and only 740 born in Kiribati.

It would have cost Scott Morrison little to make a similarly grand pledge, offering Australian refuge to Tuvalu and Kiribati climate-change refugees. Only a small proportion of these Tuvaluans and iKiribati would choose to come to Australia, as many would opt to join their relatives in Fiji or New Zealand. Yet those who did chose to move would be industrious contributors to the Australian community. Just as importantly, the offer would have been important for the presentation of Australian foreign policy.

Of course, Pacific Island politicians will continue to accept roads or sports stadiums or parliament houses “given” to them by China through aid or soft loans (or some other under-the-table incentives).

Yet for an Australian government regularly under siege internationally over its climate-change policies (or lack of them), a relatively cheap gesture to accept climate refugees from the tiny islands of the region would have signalled to the world, “We are doing our bit.” This, along some other equally strong ties with the Pacific not usually featured in current political and media discussion in Australia, could also have important economic and political benefits.