The recent publication of Peter Hartcher’s Quarterly Essay Red Flag: Waking Up to China’s Challenge coincided with fast-breaking stories about Chinese espionage and influence operations in Australia, the leaking of the Xinjiang Papers from inside China, and the overwhelming victory by Hong Kong’s democratic movement in district and local council elections.

Hot on the heels of Hartcher’s monograph came the news that a task force set up under the 2018 foreign interference legislation had finally been granted an operational budget. It brings the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, Defence Intelligence Organisation, the Australian Federal Police, and the Australian Signals Directorate together to confront the “existential” threat to our institutions from Chinese espionage and influence operations declared by recently retired ASIO chief Duncan Lewis.

The Chinese government not only denies that Wang is an intelligence defector, but declares with a droll audacity that it doesn’t conduct espionage in Australia and would never dream of interfering in the internal affairs of this country.

This is the context in which to think about the “defection” and request for asylum by Wang Liqiang. He claims to have been a Chinese intelligence officer involved in operations here, in Hong Kong, and against Taiwan. Given that his debriefing is ongoing, it may be a little premature to reach confident conclusions about both his past and his bona fides. But the case itself needs to be put in deeper perspective, whatever the final outcome of his questioning.

The Chinese government not only denies that Wang is an intelligence defector, but declares with a droll audacity that it doesn’t conduct espionage in Australia and would never dream of interfering in the internal affairs of this country. It asserts that Wang is simply a fraudster running from the law in China. Now pretty much anyone would be justified in running from the law in China, given the lack of judicial independence and due process there. But it’s at least possible that, in the case of Wang, the Chinese authorities are telling the truth.

If it should transpire that ASIO and the AFP reach the conclusion that Wang is not a Chinese intelligence operative but a fraud on the lam, it will be rather embarrassing for those who hastily embraced his claims. It will, on the other hand, reflect well on our system overall – its probity and the independence of judgement residing in different agencies and arms of our free press. Rather than emote about it, we should watch and await the finding.

In the meanwhile, it will repay us to see the incident in the perspective of the bigger picture of Chinese operations and the history of espionage and defection in the Cold War. In this regard, there are three things that ought to shape our judgement.

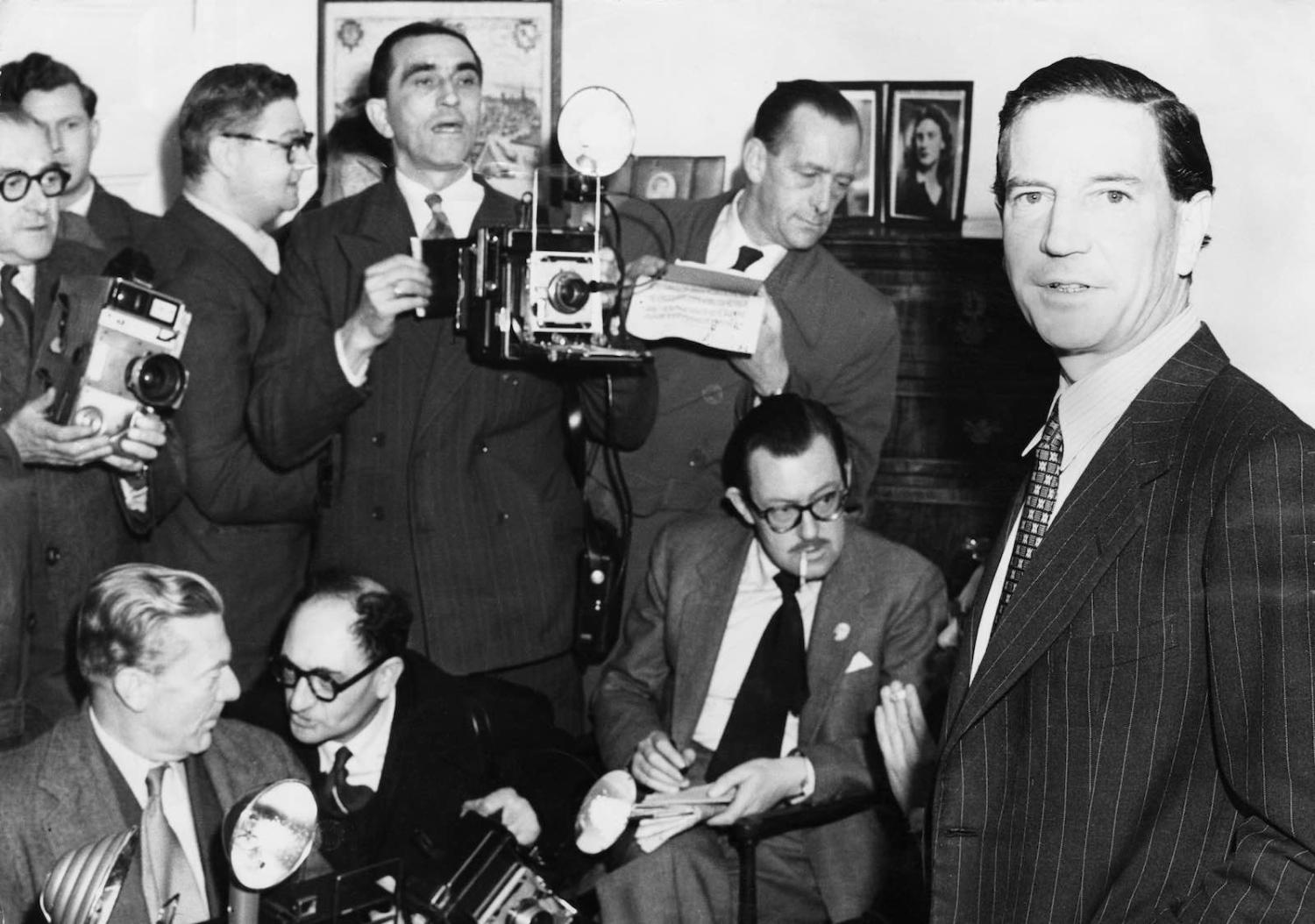

The first is that Cold War espionage saw many defections, chiefly of Soviet bloc intelligence officers to our side, and of Soviet moles fleeing exposure and heading for Moscow, such as Britain’s Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean in 1951 and Kim Philby in 1963. Vanishingly few Western intelligence officers defected to the Soviet bloc. In Australia, the 1954 defection of KGB officer Vladimir Petrov was a big story. There has, perhaps, been some expectation that Wang is a Chinese Petrov. That is in doubt.

The second consideration is that the things Wang has been talking about, whether or not he participated in them, have been taking place: espionage and influence operations in Australia, kidnappings in Hong Kong, attempts to subvert democracy in Taiwan. And, whether or not Wang turns out to be a genuine defector, we should not make the mistake of thinking that the realities of those large matters stand or fall on his claims.

The third is that we should certainly be seeking to encourage defectors to come across from the Chinese intelligence services. The perhaps overhasty enthusiasm about Wang is clearly tied to anticipation about what a serious defector could reveal. Here the Cold War background is worth revisiting.

Stalin ruled what Vladimir Petrov would call an “empire of fear”. This led quite a few of his agents in the West to defect and spill the beans on how his regime was being run, how he ruled by terror, and how he had planted moles inside Western intelligence agencies. Among these defectors was the GRU cipher-clerk Igor Gouzenko, who defected in Ottawa in 1945. He revealed the identities of some 20 Soviet moles or spies in Canada.

Walter Krivitsky, the clandestine head of Stalin’s military intelligence operations in Western Europe, based in The Hague, defected in 1937. He fled to Washington and was debriefed both there and in London.

His warnings about Soviet penetrations went largely unheeded, unfortunately. But he wound up dead in a hotel room in Washington DC in February 1941. The verdict was suicide, but serious historians of the matter have long believed he was murdered by Stalin’s agents.

I immediately thought of Krivitsky when I read about Bo “Nick” Zhao being found dead in his hotel room in Melbourne. Not because I thought Zhao was a figure of anything like the stature of Krivitsky – it was just an association of ideas. But I mention it because if we or our allies could induce the defection of a Chinese Krivitsky, we would stand to learn a very great deal. We should approach the Wang case strategically with this kind of goal in mind.